LONDON: Al Jazeera has again been criticized for allegedly justifying violence, after it broadcast unchallenged comments by the leader of Yemen’s Houthi militias urging the bombing of Saudi Arabia and Israel.

The Qatari broadcaster on Saturday tweeted comments apparently made by Abdul Malik Al-Houthi in reaction to the recent missile strikes on Syria.

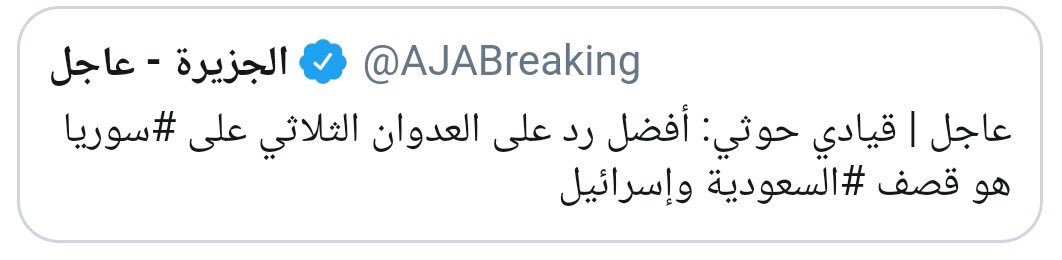

The US, the UK and France early on Saturday launched strikes on positions and bases in response to the chemical weapons attack conducted by Syrian President Bashar Assad on Douma. Al Jazeera’s Arabic service tweeted: “Houthi leader: The best response to the military aggression on Syria is bombing the financier Saudi Arabia and Israel, the partner.”

That is despite the fact that Qatar itself had expressed support for the US, British and French operations against military targets used by the Syrian regime. The broadcast of the Houthi leader’s unchallenged comments was last night likened to justifying violence, with the Al Jazeera media network allegedly being used as a “weapon” by Doha, one claimed.

“Al Jazeera once again proves it is far away from neutrality, when it considers that violence against those who disagree with it is justified,” said Abdellatif El-Menawy, an Egyptian media analyst.

“Undoubtedly, Al Jazeera is not a media outlet but a weapon and a tool in the hands of the Qatari regime.”

Mohammed Alyahya, a non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council and senior fellow at the Gulf Research Center, said Al Jazeera has become a consistent platform for the Houthis since the Qatar crisis began almost a year ago.

“Its publishing of Houthi material without scrutiny is reminiscent to its controversial and widely condemned coverage of Al-Qaeda materials, most notably Osama bin Laden’s recoded speeches, after 2001,” he said.

Dr. Majid Rafizadeh, Harvard-educated Iranian-American political scientist, said that Al Jazeera “helps to achieve Qatar’s foreign policy objectives rather than assist ordinary people to acquire the truth.”

He told Arab News that the Qatari network’s reporting and tweets are “more likely incite violence, provoke terror, and provide a platform for militias or terrorists.”

“Media outlets should not be allowed to promote extremism under the cover of freedom of expression. Many have criticized Al Jazeera’s attempts to change the direction of politics in other countries in favor of Doha rather than the ordinary people of those nations, such as leaning toward the Muslim Brotherhood, supporting Libya’s armed revolt and using softer language about terrorist groups such as Daesh, among others,” he added.

“In addition, according to the American Journalism Review, critics have pointed to Al Jazeera’s ‘anti-Semitic, anti-American bias in the channel’s news content’.”

The Qatar-funded Al Jazeera has faced numerous allegations of inciting violence and being a “platform” for terrorists. In March, it was accused of providing a “platform” for the Houthi militias, having aired comments by the group just minutes after a ballistic missile attack targeting civilians in Saudi Arabia.

Many Twitter users were critical of Al Jazeera’s coverage of the attack, with an Arabic hashtag, translating as “Qatar media support Houthi,” trending. Earlier in March, the network came under fire for “normalizing terrorism” in its coverage of an attack on the French Embassy in Burkina Faso.

Ghanem Nuseibeh, founder of Cornerstone Global, a management consultancy focused on the Middle East, claimed Al Jazeera reporting on the Burkina Faso terrorist attack was skewed.

“Al Jazeera Arabic . . . refuses to call Al-Qaeda ‘terrorists,’ instead says ‘whom authorities describe as terrorists,’” he tweeted. “Common with Al Jazeera normalizing terrorism in eyes of its readers.” Al Jazeera did not respond to a request for comment when contacted by Arab News.