CAIRO: Ballet dancer Fady el-Nabarawy feels he can finally breathe again the moment he enters the gates of the Cairo Opera House after a commute from his ramshackle, poor neighborhood. This is where he and his fellow dancers practice, perform, love and create.

“Every day, I cannot wait to come here. My oxygen is here,” he said.

Ballet is in its own bubble in Egypt, removed from the surrounding society. The elite Western art form is far from Egypt’s own rich traditions of classical Arabic music and dance, let alone the electro-beat sweeping the Arabic pop music scene. The country has grown more conservative, and in the eyes of some Muslims, ballet is outright “nudity.” Social pressure to conform is overpowering, so the idea of someone dancing on stage in tights strikes many Egyptians as just plain odd.

Still, the young men who found their passion dancing ballet are hardly isolated elites. They’re firmly rooted in the middle and lower-middle classes, managing to carve out their own Bohemian zone of diversity and creativity.

Ballet’s audience in Egypt may be limited, but it’s enthusiastic. On a recent night at the Opera House, located on an upscale residential island in the Nile River, the Cairo Ballet Company brought a packed house to its feet with a rousing performance of “Zorba,” a ballet based on the same novel as the movie “Zorba the Greek.”

The audience — men mainly in suits, women in evening gowns, many wearing Muslim headscarves — cheered a dazzling finale by the two leads. Ahmed Nabil, tall and slender, leaped in classical routines while Hani Hassan, playing Zorba, mixed in the machismo of traditional Greek dance, slapping his thighs and kicking up his heels. Hassan blew kisses to the crowd and led them in clapping to the music.

The ovations pulled them out for three encores. Afterward, people swarmed to congratulate Nabil and his wife and fellow dancer, Italian ballerina Alice De Nardi.

“And to think my parents wanted me to drop out of ballet school,” Nabil said.

In the 60-member, state-funded company, almost all the ballerinas are foreigners, coming from Serbia, Italy, Greece, Japan, Ukraine and Greece, with only a handful of Egyptians. The male dancers, in contrast, are almost all Egyptian.

From childhood, the male dancers learned to keep ballet a secret. It was the best way to avoid mockery, bigotry, innuendos about their sexual orientation or just ignorant curiosity — constant questions like “Can you walk on your toes?” or “Do you wear tights?” Hassan told people he did gymnastics when they asked why he was getting so muscular.

“When I read music on the metro and some guy asks me what I’m doing, I tell him I’m with the conservatory,” said el-Nabarawy.

El-Nabarawy came to ballet because of a moment of despair as a 7-year-old. He was a reclusive child, and his teachers often yelled at him and hit him. So one day he skipped school and hid all morning behind a parked car near his home.

When his mother found out, she promised to move him to another school the next year. His father saw an ad for the arts academy. Its main attraction was that it was near their home. El-Nabarawy applied to the conservatory and failed, but then was accepted in ballet.

His mother wondered if that was more suitable for girls, but in the end didn’t object.

“I became a ballet dancer by chance but, glory to God, I’m told I was born to be a ballet dancer,” he said.

El-Nabarawy, now 29, said he’s proud both of being a ballet dancer and of being from Cairo’s district of Omraniyah, though it is not always easy.

Once farmland on Cairo’s western edges, Omraniyah is now a crowded district of shoddy, cramped concrete-and-brick apartment towers, mostly built up illegally as migrants poured in from southern Egypt looking for jobs and a better life. Narrow streets are jammed with cars, trucks, donkey carts and motorcycle rickshaws, or tuk-tuks, often driven by children.

El-Nabarawy lives with his parents and brother on the top floor of a six-story walk-up. It looks out over a cityscape of satellite dishes, dangling wires, exposed rebar and jagged concrete.

But he’s hardly there. “My life now is totally divorced from Omraniyah,” he said. “I just go home to sleep.”

Instead, his time is spent in the refuge of the Opera House complex.

In rehearsals, as the dancers sweat and strain, it becomes clear how it’s a space for some diversity. Some of the men sport a “zebiba,” a bruise on the forehead from prostrating during Muslim prayers, and head out to pray during rehearsal breaks. Others have pony tails, a style that still gets disapproving looks on the streets in Egypt.

The male and female dancers mingle, chat and smoke together. Like his Zorba, the 39-year-old Hassan, the son of an army officer, exudes joie-de-vivre, flirting with ballerinas and showing off his fluency in Russian — his ex-wife was a Russian dancer. He proclaims repeatedly he’s traveling soon to Spain for a guest performance, a badge of honor.

At least six of the male dancers are married to or dating foreign female dancers.

It’s often a lesson in broadening horizons. El-Nabarawy describes himself as a practicing Muslim — he sometimes posts religious material on Facebook — and his girlfriend, Kristina Lazovic, is a Christian Serb. El-Nabarawy grew up hearing about Serbian massacres of Bosnian Muslims during the Balkan wars in the 1990s. Now he’s getting the Serbs’ side in lively discussions with Lazovic.

“I’m now convinced atrocities were committed by both sides,” he said.

Fellow dancer Waleed Eskaros and his fiancée, Greek ballerina Antigoni Tsiouli, are making their own cultural adjustments. Both are Christian, but he’s Coptic Orthodox and she’s Greek Orthodox.

He wants his Church’s blessing, but it won’t marry them unless she converts, something she and her family refuse. So “it looks like I will marry in a Greek Orthodox church. They are more flexible.”

Presiding over the rehearsals is Madame Erminia Gambarelli, the artistic director. She’s the Italian widow of Abdel-Moneim Kamel, the giant of Egyptian ballet who rebuilt the company in the 1990s, mentored many of its current dancers and died in 2013.

Ballet in Egypt has been immersed in politics from the start.

The national company was founded by the government in 1958 as a way to strengthen the bond with Egypt’s top ally at the time, the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, President Hosni Mubarak’s government revived ballet as part of a more capitalist-driven prestige project, building the Opera House complex with Japanese backing.

Ballet was thrust onto the political stage after the Muslim Brotherhood came to power following the 2011 uprising that ousted Mubarak.

Islamist lawmakers demanded an end to state funding for the company. One legislator denounced ballet as the “art of nakedness.”

Some dancers had often worried privately over whether ballet was acceptable under their faith, Eskaros said. The Islamists tipped them over the edge, and several quit, declaring it “haram,” or forbidden.

Fears over the fate of ballet and other arts became a rallying point in the popular campaign against the Brotherhood. When an Islamist was named culture minister in 2013, artists and intellectuals held a month-long protest outside the minister’s office.

It turned into a nightly street party of singing, poetry and dancing. Hassan, Eskaros and others in the company performed a dozen times. “I thought I’d dance on the street to let people decide for themselves whether ballet is haram or not,” Hassan said.

The military ousted the Brotherhood in July 2013.

Hassan remains a fierce opponent of “conservative ideologies” he says pervade the country. “People inject religion into everything ... always talking about what this sheikh said and what that sheikh said.”

The company is still recovering from the turmoil. Most foreign dancers fled amid the 2011 uprising. Foreign ballerinas are back, but now the company — like the rest of Egypt — struggles with austerity measures imposed by the government to repair the damaged economy.

Funds are tighter. After devaluations, even the best paid dancers make the equivalent of only a few hundred dollars a month. Nabil and Hassan run ballet schools, making a living and spreading the art. Others teach ballet or take up day jobs, mostly in the government.

“I’m not happy with the quality of our work,” said the 34-year-old Nabil. “The company is now rebuilding.”

Still, he said, his entire life is within the Opera House walls, where he’s been coming since he was 11.

“This is where I am famous. Once I go through the gate and onto the street, I cease to exist as who I am.”

Ballet isolated in Egypt but it fires passions

Ballet isolated in Egypt but it fires passions

REVIEW: ‘Returnal’ — a thoughtful and challenging sci-fi adventure

LONDON: Right from the start, before you even take control of Selene Vassos, a reconnaissance scout who has crash landed on a prohibited and mysterious planet, you are warned that “Returnal” (available originally for PS5 but now PC too) is “intended to be a challenging experience.” Such difficulty may deter the casual gamer used to a steady progression of character and exploration through a games environment. However, “Returnal” is a thoughtful and rewarding adventure that lays claim to much originality of thought in its set up. The key theme is that when you die, you return! But not to the same environment that you were in before. Instead, each new cycle postures new challenges and progress can only be made by unlocking upgrades that allow you to make more meta progress in Selene’s journey.

Selene herself is a super professional, unfazed character who doesn’t appear too bothered when she comes across a body of her former self that died in this strange world where the laws of physics and time appear not to apply. Staying alive is obviously crucial, particularly as it allows her to retain better weapons for longer. In addition, avoiding damage allows for boosts of agility, vision and more, making for a more lethal Selene. The environment is varied and surprising with each incarnation and the weapons on offer come complete with a range of exciting alternative fire mechanisms such as homing missiles or laser-like items. A hostile environment where even plants are a threat to life is mitigated by your technology, the core of which you can improve despite the reset of deaths, through fancy smart “xeno-tech” that becomes integrated with alien kit left around.

There is a paradox in “Returnal” described by Selene herself that she is trapped in an environment that is “always the same, always changing,” which literally makes no sense. Players have to be patient in the early chapters getting used to the sapping dynamic of death and return. Once that makes more sense, the loneliness of both her alien environment and the impossibility of even dying to escape it make for a pretty special atmosphere that a smart shooting engine then complements.

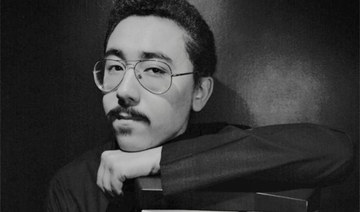

Artist Abdullah Al-Saadi represents the UAE at Venice Biennale

VENICE: Emirati conceptual artist Abdullah Al-Saadi is representing the UAE at the 60th Venice Biennale, curated this year by Adriano Pedrosa under the theme of “Foreigners Everywhere. Stranieri Ovunque.” The pavilion’s exhibition, which opened on April 20 and runs until Nov. 24, was curated by Tarek Abou El-Fetouh.

Al-Saadi has played a pivotal role in the development of the UAE’s evolving art scene — his multidisciplinary practice includes the mediums of painting, drawing, sculpture, performance and photography, as well as collecting and cataloguing found objects and the creation of new alphabets.

“Since I was a student, four decades ago, art has been an integral part of my daily life,” Al-Saadi said in a statement. “My art is the result of interactions with places, people, ideas, and aesthetics that I encounter every day where I live and in my journeys. I find myself driven to document these experiences visually or in written diaries and contemplations, seeking to transfigure the ordinary with the passage of time.”

“I am representing myself in Venice as an artist foremost and then as a local Emirati artist,” Al-Saadi told Arab News. “This pavilion will showcase my artistic journey over a long period of time since after university through eight works, two of which are new commissions,” he said of the ongoing show titled “Abdullah Al-Saadi: Sites of Memory, Sites of Amnesia.”

One of the artistic journeys he made that will serve as a new artwork took place amid the Arabian landscape.

“I spent seven days in the valley studying the tea, the coffee, and bread,” Al-Saadi explained to Arab News. “Then after one week I rode my bicycle, and I went to the mountains. During that time, I was reading a book on the Silk Road and trying to imagine how it was to travel on the Silk Road and I compared my way of traveling with how it was to travel on the Silk Road long ago.”

“Abdullah’s work is comprised of multiple aspects, from his diaries to sketches, to landscapes, scrolls and other objects that he creates,” Laila Binbrek, Director of the National Pavillion UAE, explained to Arab News. “They all stem from his diary — a diary he has been keeping for the last 40 years. Every day he writes in his diary.”

Christie’s Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds auction highlights rare finds in London

LONDON: Christie’s Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds spring sale will see 261 lots —including paintings, ceramics, metal work, works on paper, textiles, rugs and carpets — go under the hammer at a live auction at their London headquarters on April 25.

Arab News was given an exclusive viewing of some of the works prior to their public pre-sale showing from April 21-24.

Sara Plumbly, Christie’s Head of Department for Islamic and Indian Art, gave her expert insights into some selected pieces.

These included lot 45, an exquisite miniature octagonal Qur’an, dated AH 985/1577-8 AD, which was made in Madinah, the Qur’an has an estimate of $13,000-19,000.

“We very rarely see manuscripts that were copied in the holy cities. So this being copied in Madinah makes it very rare,” she explained.

“It has a Naskh script. This a very steady, cursive script which is relatively easy to read — unlike some of the others. For example, Nastaliq script, which is copied on the diagonal, is much trickier to read. For Qur’ans you would almost always see a Naskh script for ease of reading. Nastaliq is usually reserved for poetic manuscripts,” she said.

This miniature Qur’an would be small enough to carry with the owner on a daily basis, usually around the neck. Alternatively, they would be hung in their silver boxes on an ‘alam (standard or flag) and carried into battle.

Plumbly, who completed her master’s degree in Islamic Art and Archaeology at the University of Oxford, has lived and travelled extensively across the Middle East and North Africa, including extended periods in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Sudan.

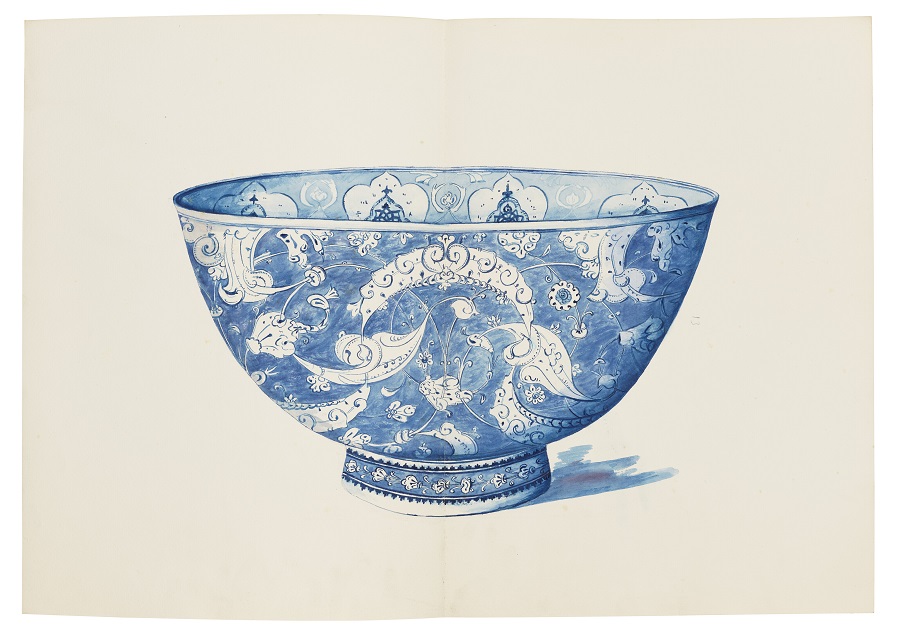

Another stunning item in the sale is a Watercolor Album depicting a selection of known prestigious and rare Iznik ceramics from the Louis Huth collection. It comprises 44 single and double-page watercolor paintings of Iznik bowls, flasks, ewers and dishes.

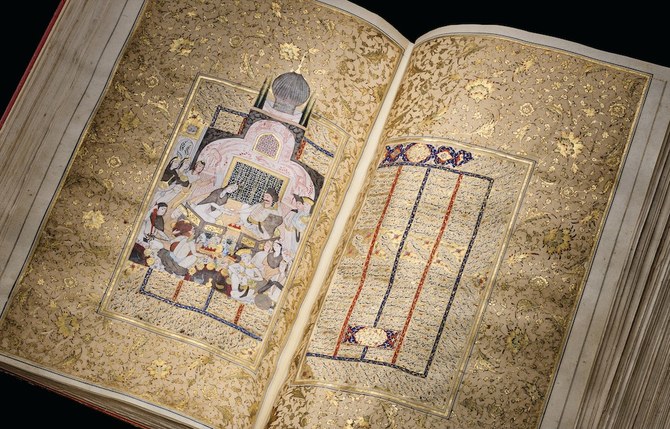

It was also fascinating to see a rare and complete illustrated manuscript copy of the Khamsa of Nizami by 12th century Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi, together with the Khamsa of Amir Khusraw Dihlavi, a 13th century Persian Sufi singer, musician, poet and scholar. The colors in the illuminations leap off the pages as though created yesterday.

Plumbly also pointed out the exceptional workmanship of an early 13th century Kashan pottery bowl, excavated in Iran’s Kashan in 1934.

“This type of Kashan ceramics have a wonderful luster. It’s a very difficult technique to perfect. This bowl has a really beautiful dark gold color which is very well controlled. The condition is remarkable. It’s one of those ‘best of type’ objects,” Plumbly observed.

Merwas — Riyadh’s beating heart of creativity

- World’s largest music production studio is nurturing Saudi talent, streamlining local industry

RIYADH: Riyadh’s Merwas, considered the biggest art and entertainment factory globally, is proving to be one of Saudi Arabia’s greatest music industry assets.

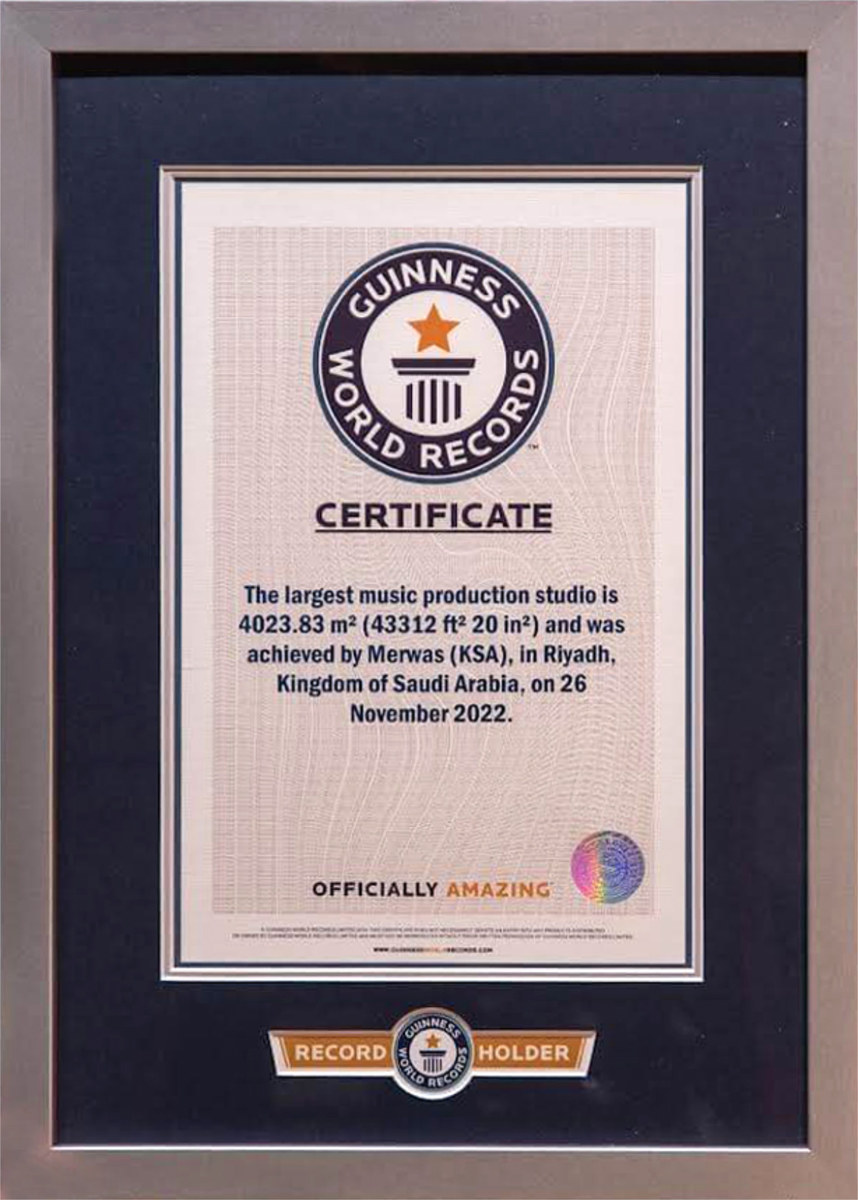

Nada Al-Tuwaijri, co-founder and CEO of Merwas, told Arab News that the facility, which holds the Guinness World Record for the largest music production studio, “is home to all artists.”

She added: “The methodology behind it is to create solutions through the subsidiaries, and invest in both talent and infrastructure.

“Alongside it being a one-stop shop for all content creators, we strive to take our local talents from local to global and create a unique stamp in the industry.”

The entertainment zone and audiovisual production studio, located in Boulevard Riyadh City, houses 22 main studios alongside its academy.

Some of the top musicians in the world have visited Merwas since it opened in 2022. These include DJ Khaled, the acclaimed Saudi singer Rabeh Saqer, and the Emirati singer Ahlam. Afrojack, a world-renowned Dutch DJ and producer, also led an electronic music boot camp to nurture local talent and inspire a new generation of Saudi artists.

HIGHLIGHTS

• Merwas, located in Boulevard Riyadh City, houses 22 main studios alongside its academy.

• The academy’s classes offer local creatives and artists direct access to seasoned expertise.

• The Earth Sound Studio, or ESS, named after the late Saudi composer Talal Maddah.

Spread across almost 5,000 square meters, the culture factory fosters creativity, collaboration, and the production of multimedia content, while providing artists with access to top-tier services, facilities and industry expertise.

The Earth Sound Studio, or ESS, named after the late Saudi composer Talal Maddah, features state-of-the-art technology, such as the SSL console, which is used to create depth on music tracks and ensures the true soul of the artist’s voice is protected.

This live recording space is booked almost every day by various artists, and has been used by some of the Arab region’s biggest stars.

One of the only five Neve consoles in the world can be found in the Neve Studio. The panel is known for its high-quality sound and warmth, and is ideal for music recording, vocal tracking, and mixing for exceptional audio quality.

Its live studio can accommodate over 120 orchestra members and their instruments to provide a unique recording experience.

Specifically designed for electronic music production, the EMP Suite is a DJ’s dream, with cutting edge synthesizers and digital audio workstations ensuring an artist leaves the room with a fully produced track.

Merwas is also home to three production suites, designed for content creators who require a comfortable and professional environment for music production, editing, and mixing. Each suite is equipped with industry-standard gear, software, and acoustics to support a wide range of projects.

The studio also provides private rehearsal spaces to ensure Saudi talents are nourished to their full potential. The versatile space is designed for musicians, performers, and other artists to rehearse and refine their craft within a comfortable environment with access to instruments and equipment.

Part of the charm of recording studios is the live jam sessions that have given birth to some of the most iconic records to date. Merwas’ Band Live/Control Room also captures the spontaneity of live performance within its soundproof walls.

Alongside (Merwas) being a one-stop shop for all content creators, we strive to take our local talents from local to global and create a unique stamp in the industry.

Nada Al-Tuwaijri, Merwas cofounder and CEO

Championing audiovisual pursuits, the studio has made space for high-quality podcasts and videos to come to life.

The podcast suite and FM radio recording spaces are tailored to immerse listeners with unbeatable audio clarity, while the 25-meter-long Green Screen room helps ideas come to life, whether commercial, film, or music video.

Material can then be edited at the color-grading suite, which is essentially a small theater with 4K projector. Producers, directors, writers, and engineers gather here to put the final visual touches on video projects through its DaVinci color grading software and hardware.

Academy Classes offers local creatives and artists direct access to seasoned expertise. These feature advanced stations for sound production, engineering, and technical programs, with everything necessary for a basic understanding and training of music production.

The studio hosts workshops, networking sessions, and community events in an effort to flourish the music industry locally while making it a magnet for international talent. Anyone can be a part of this community by booking a suite or signing up for a workshop on their website merwas.sa.

Merwas has positioned itself at the the forefront of the entertainment industry being the first of its kind in the MENA region. In less than a year since its launch, it has already became a hotspot for musicians across the globe to visit and utilize its services, from rising talents to international A-listers.

Founded by Al-Tuwaijri and Chief Content Officer Rumian Al-Rumayyan in partnership with Sela, Merwas treasures Saudi creativity and is a vital part of building an ecosystem and community for local artists.

Their partnership with the Saudi Authority for Intellectual Property has set a new focus on preserving the rights of local creatives, pillared by the aim to enrich the culture of the Kingdom while empowering its citizens and their creativity in an environment of abundant knowledge, education in culture, art, entertainment and music.

Hollywood Arab Film Festival: Showcasing Arab cinema in Los Angeles

LOS ANGELES: The third annual Hollywood Arab Film Festival began this week, bringing the best of 2024’s Arab cinema to Los Angeles and giving fans a chance to see the films in theaters as well as introducing a new audience to the Arab world’s top talent.

The event, which runs until April 21, was attended by a number of celebrity guests including Egyptian producer and screenwriter Mohamed Hefzy, Tunisian actor Dhaffer L’Abidine, renowned Egyptian star Elham Shahin and Egyptian producer Tarek El-Ganainy.

At the event, Hefty said: “Arab cinema really needs a platform to tell our stories and to show who we are, our identity, our hopes and dreams, our pains, and all the different social topics that are tackled in some of the films that are being presented are maybe more relevant today than ever. So I think it’s a great opportunity to have this dialogue.”

Hefzy’s film “Hajjan” was showing at the event. It is a Saudi Arabia-based film directed by Egyptian filmmaker Abu Bakr Shawky.

“Hajjan is a film about a young boy who got a very special connection to his camel, who has a brother who was a camel jockey and races,” Hefzy said. “And, one day when something really unexpected happens to his brother, and shatters his world, it forces him to step into his brother’s shoes and become a camel jockey, and so starts racing himself.”

The movie is a co-production between the Kingdom’s King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture, or Ithra, and Hefzy’s Film Clinic.

“It was a film made in Saudi Arabia with Saudi talents and actors with an Egyptian director, but with the Saudi co-writer and Saudi actors and shot mostly in Saudi Arabia,” Hefzy said. “So I think it’s, it was a great experience, and learned a lot about Saudi Arabia, learned a lot about the culture.”

The festival featured cinema from various Arab countries, presenting films from 16 different nations. Marlin Soliman, strategic planning director of HAFF, highlighted the inclusion of six feature films, ten short films and six student films.

Spanning five days, HAFF offered its audience a vibrant experience, including a red-carpet affair, panel discussions on filmmaking and diversity in Hollywood, and, of course, screenings of high-profile films.

The festival also saw several filmmakers singing the praises of Saudi Arabia’s expanding film industry.

L’Abidine, the writer and director of “To My Son,” said: “I’m thrilled to be back again with my second feature film ‘To My Son,’ a Saudi film… I think there is a great evolution of Saudi cinema that’s been happening in the last few years.”