DAVOS: Philanthropy has the power not only to do great good, but to do so in a way that stimulates additional capital investment from business and government sources, Emirati businessman Badr Jafar told Arab News on the sidelines at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Jafar knows a thing or two about the subject. In addition to his roles as CEO of Crescent Enterprises, a multifaceted business operating across nine sectors in 15 countries, and chairman of Gulftainer, the largest privately owned container-port operator in the world, he is special envoy for business and philanthropy for the UAE, holds multiple advisory positions in the humanitarian and development sectors and co-founded the Arab World Social Entrepreneurship Program.

“The term philanthropy itself conjures up this image of the sort of billionaire donor who has lots of money to give away, and I don’t like that,” he said.

It is problematic, Jafar said, because far from simply flinging money around in the hope that some of it sticks, many philanthropists operate in a far more sophisticated way.

“Capital today is a continuum, and impact is also a continuum,” he said.

“And the sooner we start to see the benefits of alignment of capital across government, business and philanthropy, the sooner we can start to reap the rewards that come with the multiplier effect that’s generated when these pools of capital work better together.”

Philanthropy, he said, is “the forgotten child of the capital system, regarded in some parts of the world as a peripheral player, and in other parts regarded with a high degree of suspicion.”

In fact, in its best form philanthropy can act as a catalyst: “Philanthropic capital, often referred to as catalytic capital, can help to de-risk and crowd in other sources of capital, particularly from the business sector. There are many examples from around the world where donated capital without any intended financial return goes in to unlock opportunities for businesses, including in tech.”

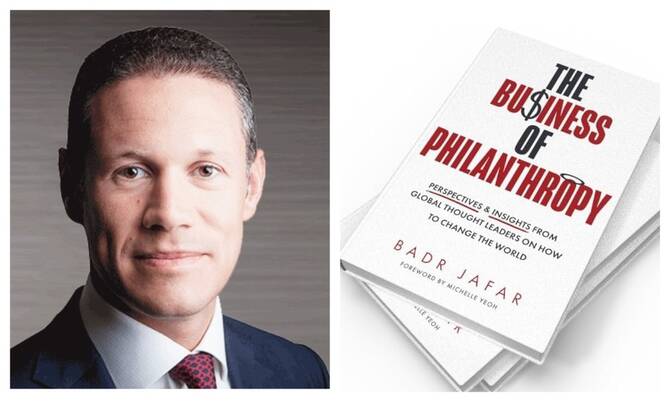

Emirati businessman Badr Jafar. (Supplied)

He also feels the sheer scale of philanthropic capital is seriously under-appreciated.

“Take the US example. The recent reductions in USAID was a shock to the system. But to put things into perspective, at its peak in about 2023 USAID was less than $50 billion a year. Now that’s a significant amount of money, but private philanthropy alone in the US in that same year — and to clarify, this is excluding corporate philanthropy — was well north of $600 billion.

“Now I’m not suggesting that private philanthropy is a substitute for official development assistance — aid from government, and the nature of aid from government, is extremely important, particularly in certain settings, including humanitarian.

“But today global philanthropy is pushing $2 trillion a year, more than three times the global humanitarian and development aid budgets, and that’s a lot of money.”

Jafar is the author of “The Business of Philanthropy: Perspectives and Insights from Global Thought Leaders on How to Change the World,” a collection of discussions with 50 of the world’s most active philanthropists, including Microsoft founder Bill Gates, the Bulgarian economist and managing director of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, and Razan Al-Mubarak, head of the Environment Agency Abu Dhabi and president of the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The title of the book, he said “was purposefully provocative, getting people to think about what the business world has to learn from philanthropy and what philanthropists have to learn from the business world.”

Through the examples, insights and experiences of his high-profile interviewees, he makes the case for what he calls “strategic philanthropy,” in the hope that others may be inspired to follow in their footsteps.

“The need for strategic philanthropy in the world today,” he writes, “is greater than ever. The geological fractures that constitute the headlines every day — regional conflicts, political extremism, and the resulting refugee and humanitarian crises — are compounded by environmental challenges.

“Public- and private-sector leaders in all countries are grappling with these issues daily. More than ever, strategic philanthropists across the world have an opportunity to step up to help meet those challenges.”

Jafar grew up in Sharjah, in a family “with a strong belief in giving back to the community.” The book is dedicated to his mother and father, “who taught me everything I know and are still working on teaching me everything they know.”

All royalties from the sale of Badr Jafar’s book are donated to the International Rescue Committee, in support of children affected by armed combat.