DUBAI: Inside Abu Dhabi Royal Equestrian Arts, a new institution brings together centuries of horsemanship and the written word. The ADREA Library, the Middle East and North Africa region’s first all-equestrian library, has been carefully curated by Isobel Abulhoul, whose influence on the UAE’s literary landscape spans more than five decades.

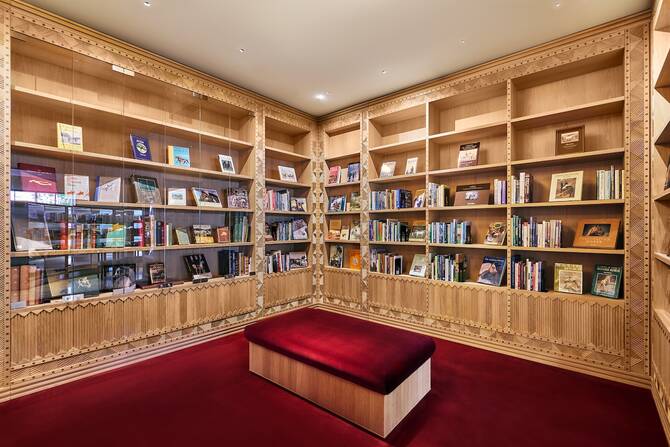

“The ADREA Library is infused with the spirit of horses,” said Abulhoul in an interview with Arab News. Its shelves hold more than 14,000 titles dedicated entirely to equestrianism, encompassing “every aspect” of the field — from equine history and breeding to veterinary health, polo, racing, dressage, show jumping, training and saddlery. The result is a collection as comprehensive as it is specialized, designed to serve scholars, riders and enthusiasts alike.

Its shelves hold more than 14,000 titles dedicated entirely to equestrianism, encompassing “every aspect” of the field. (Supplied)

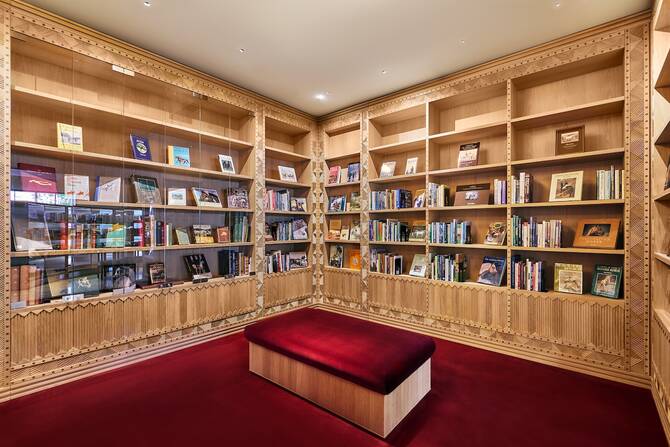

Beyond its scope, Abulhoul believes the library’s emotional resonance sets it apart. “It is a space that speaks across centuries, with a sense of legacy,” she said, pointing to stories of famous horses through history.

In the region, where the horse occupies a cherished cultural position, the library taps into a deep-rooted heritage. Arab horses, bred for centuries for “their loyalty, their speed and their beauty,” are central to that narrative. Visitors, she hopes, will be drawn into the collection and intrigued to learn more as they browse.

For Abulhoul, the project unites two lifelong passions. Since arriving in the UAE in 1968, she has played a defining role in shaping its reading culture, from co-founding Magrudy’s Bookshop in 1975 to founding the annual Emirates Airline Festival of Literature.

Beyond its scope, Abulhoul believes the library’s emotional resonance sets it apart. (Supplied)

But horses have always run alongside books in her life. She recalls helping to establish the Dubai Equestrian Centre in the 1980s, importing pure-bred Arabian horses and riding with her children through the desert. “Horses always can find their way home,” she said.

Being asked to curate the ADREA Library, she added, “was a dream come true.”

She sees strong parallels between fostering a literary community and nurturing equestrian excellence. “Humanity’s connection with horses is so special,” she said, describing them as noble creatures that respond to “gentleness and kindness.”

The ADREA Library has been carefully curated by Isobel Abulhoul. (Supplied)

Books, too, are teachers. “Both books and horses can nurture our creativity and empathy,” she said. “We can learn much about ourselves when we ride and when we read.”

That philosophy shapes the library’s role in preserving Emirati heritage. Abulhoul references Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al-Nahyan’s words: “A nation without a past is a nation without a present or a future,” and his declaration of a love for horses “rooted deeply in the history of our people.”

A dedicated children’s and youth section aims to spark both an interest in horses and “a love of reading for pleasure” among younger generations.

Assembling the collection took over a year of research into equestrian publishing worldwide. The final selection spans Arabic and English titles, with additional works in Spanish and Portuguese, including books on the Spanish Riding School. Rare and out-of-print volumes were sourced globally, and the collection is fully catalogued using the Dewey system, supported by specialist software that allows members to borrow titles.

Looking ahead, Abulhoul envisions steady growth, guided by community needs and borrowing patterns. Over time, the ADREA Library will continue to expand — organically and always with horses at its heart.