JEDDAH: Celebrities from across the world gathered in Jeddah on Thursday for the closing ceremony of the Red Sea International Film Festival.

Although the 2025 edition officially wraps up on Dec. 13, the Yusr Awards Ceremony took place in Jeddah’s Al-Balad on Thursday night.

Idris Elba. (Getty Images)

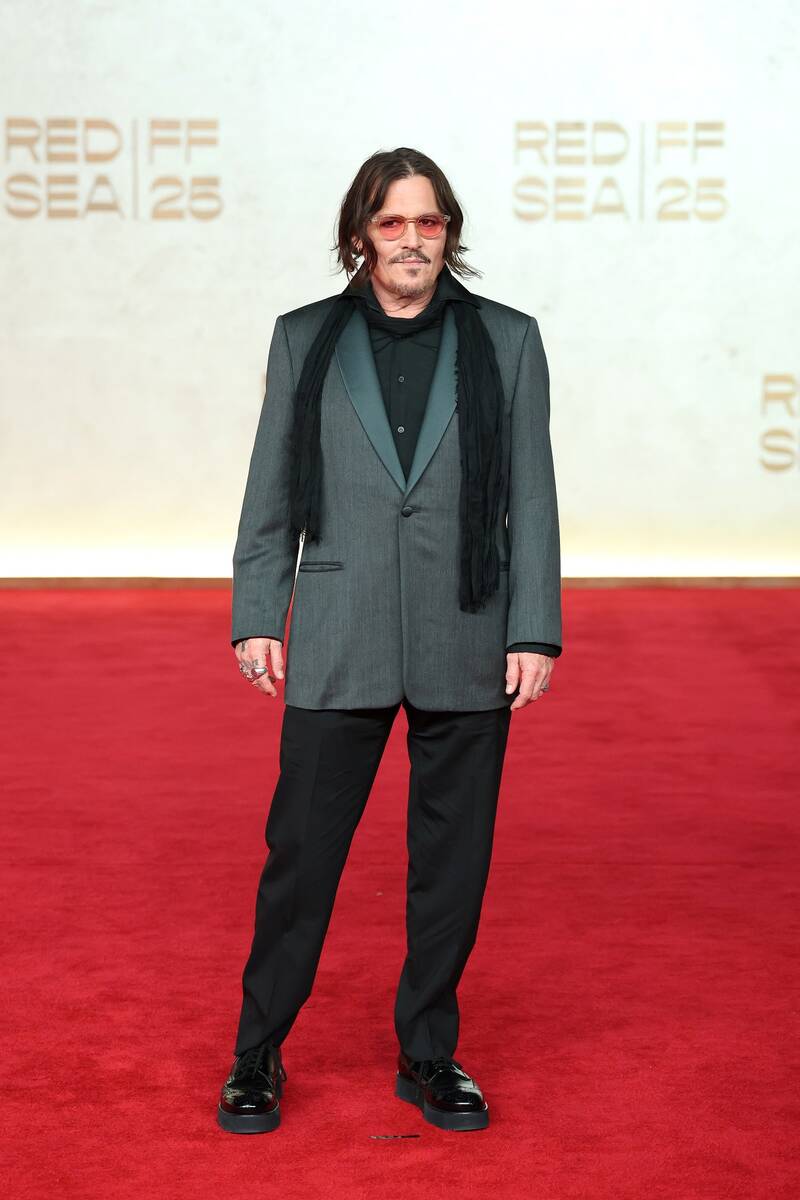

The red carpet ahead of the ceremony hosted the likes of British actor-director Idris Elba, Welsh actor Anthony Hopkins, US star Johnny Depp, US Venezuelan actor Edgar Ramirez, British Malaysian actor Henry Golding and US director Darren Aronofsky.

Darren Aronofsky. (Getty Images)

“It's been completely eye opening and unexpected in so many ways and I've learned so much,” “Black Swan” director Aronofsky told Arab News on the red carpet.

“I've been inspired by young filmmakers… it's always interesting to bring attention to young new filmmakers. And what's exciting about Red Sea is it's very focused on here and Africa and Asia and trying to bring it all together.”

On his advice for upcoming Saudi filmmakers, he said: “It's an opportunity for new voices like we've never seen before. Because it's like clearly such a huge culture and tradition and the stories haven't been told … I'd probably tell young filmmakers to ‘tell your own story.’”

Andria Tayeh. (Getty Images)

Bollywood’s Salman Khan was also in attendance.

Salman Khan. (Getty Images)

From the Kingdom, Saudi actresses Maria Bahrawi, Sarah Taibah and Summer Shesha attended, as well as Saudi filmmakers Shahad Ameen and Ali Kalthami, among others.

Sarah Taibah. (Getty Images)

From the region, actress Andria Tayeh was joined by Dorra Zarrouk, Rym Saidi and Saba Mubarak.

The jury also attended the closing ceremony, including jury head Sean Baker, Lebanese director Nadine Labaki, British Oscar winner Riz Ahmed, actress Olga Kurylenko and actress Naomi Harris.

"I'm just blown away by how much talent there is and how unfair it is that so many voices haven't had the platform that they truly deserve," Harris told Arab News.

Summer Shesha. (Getty Images)

On the night, 15 awards will be handed out to competition titles, as well as actors and actresses.

Now in its fifth year, RSIFF returned with the theme “For the Love of Cinema” and has so far screened more than 100 films from Saudi Arabia, the Arab world, Asia and Africa.

Maria Bahrawi. (Getty Images)

The Arab Spectacular program featured regional titles including “Palestine 36” by Annemarie Jacir; Haifaa Al-Mansour’s “Unidentified”; and “A Matter of Life and Death” by Anas Ba-Tahaf, starring Saudi Actress Sarah Taibah.

The International Spectacular section saw screenings such as “Couture” starring Angelina Jolie, “The Wizard of the Kremlin,” “Scarlet,” “Farruquito — A Flamenco Dynasty,” and “Desert Warrior,” which was filmed in Saudi Arabia.

Johnny Depp. (Getty Images)

Beyond screenings, perhaps the most anticipated part of the festival is its In Conversation talks, where global stars spoke candidly about their careers.

The likes of Dakota Fanning, Aishwarya Rai Bachan, Adrien Brody and Nicholas Hoult are just a handful of the stars who took part in the sessions, reflecting on their careers and often giving advice to members of the audience.

Naomi Harris. (Getty Images)

The festival’s marketplace — the Red Sea Souk — also returned from Dec. 6-10 with more than 160 exhibitors from more than 40 countries, industry panels, project-market pitches, masterclasses and networking sessions.