DUBAI: Surveying the landscape of Gaza after two years of Israeli bombardment, it is clear the damage inflicted on the Palestinian enclave will take decades to repair. The wounds sustained by civilians, both mental and physical, will likewise last a lifetime.

However, new research suggests the scars of the conflict may be felt by generations who have not even been born yet, with the effects of trauma shaping the very DNA of Gazans themselves, leaving a genetic footprint on the Palestinian people.

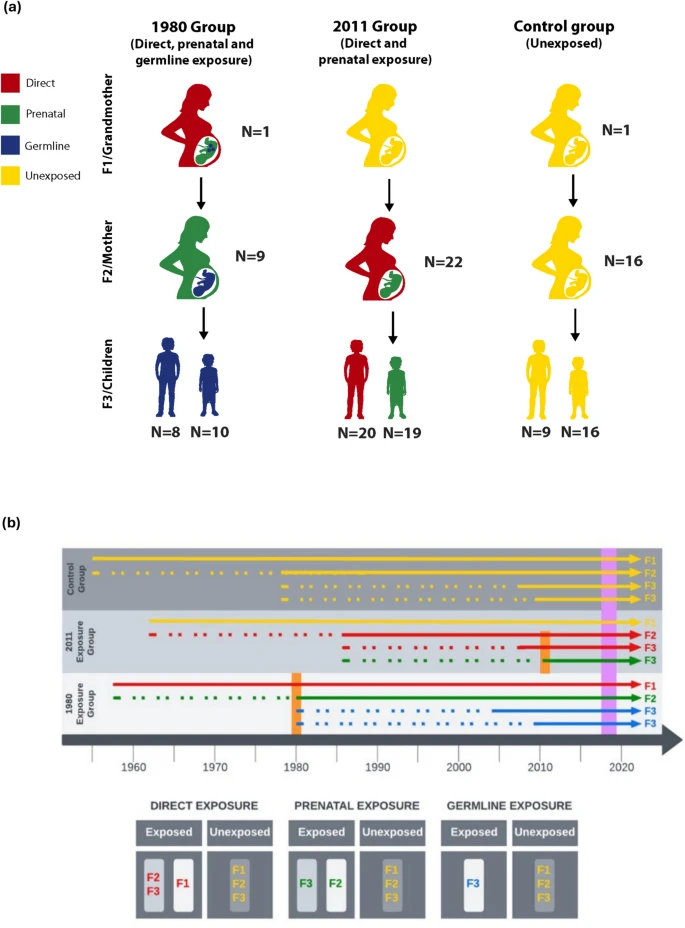

According to a paper by an international team of researchers titled “Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees,” trauma can edit our genome, altering how our bodies adapt to our environment.

“We know usually that epigenetic signatures are erased every generation,” Rana Dajani, professor of genetics and molecular biology at the Hashemite University of Jordan, who led the research, told Arab News.

“But what we found is that 14 sites of the genome were altered as a result of a grandmother’s exposure to violence had been passed through to her grandchildren, who themselves were not exposed to violence at all.”

Caption

Epigenetics works like a light switch for genes, with DNA working like a big instruction manual. If we imagine each gene as a light bulb, epigenetics does not change the light bulbs but instead controls which ones are turned on or off.

Even if a child has not been exposed to conflict, Dajani says signatures of the violence can continue to linger in their genetic code from past generations, impacting the way their bodies react to their environment — or which genes are switched on and off based on various stimuli.

This means that the grandchildren of someone who has experienced conflict may be at risk of developing the same vulnerabilities as someone who has directly suffered trauma in their lifetime.

Professor Rana Dajani. (Wikimedia Commons)

“We found that for women who are directly exposed to violence, 21 regions of their genome had epigenetic changes,” Dajani said.

“We have not been able to tie those to any particular health outcomes, but we already know from other research that anybody exposed to trauma in the past can demonstrate some outcomes, whether it’s mental health or cardiovascular or diabetes or even cancer.

“These kinds of results help us to really understand what the impact of the genocide in Gaza could be.”

The war in Gaza was triggered by the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas-led attack on southern Israel, which killed 1,200 people, most of them civilians, and saw 251 taken hostage. The resulting Israeli assault on Gaza has killed at least 67,000 people, according to local health officials.

Displaced Palestinian children play in a destroyed car in the Bureij refugee camp, in the central Gaza Strip on November 10, 2025. (AFP)

Israel’s embargo on humanitarian assistance entering Gaza led to famine conditions in several areas of the enclave. The alleged use of starvation was a weapon of war prompted multiple accusations of genocide — claims that Israel vehemently denies.

A fragile ceasefire came into effect on Oct. 10, allowing humanitarian aid to flood into the territory. However, violence has continued to flare, infrastructure lies in ruins, and at least 90 percent of the population remains displaced.

Connie Mulligan, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Florida who worked with Dajani on the research, said both physical and psychological trauma could result in epigenetic signatures.

Mulligan says the impact may differ depending on the type of trauma, but these differences have yet to be explicitly mapped. Although her research focuses primarily on psychological stress, she believes physical stressors are also likely to have an impact.

Professor Connie Mulligan. (Supplied)

“Being exposed to environmental toxins will have similar but distinct impacts on the individual, including epigenetic marks, compared to psychosocial stress,” Mulligan told Arab News.

She said the “startling” discovery that epigenetic changes were able to carry generationally was important to reshaping conversations around recovery and rehabilitation. She hopes this would mark the start of a new understanding of trauma.

“Psychosocial stress sometimes gets dismissed — it’s just stress, just get over it. But what we are increasingly finding with all this research is that you can’t just get over it,” she said.

“Now we’ve got individuals who didn’t even experience it but still have a molecular signature of the event, and the question is how can they get over it? Because it’s something in there. It’s something in their epigenome.

“If we could better understand that, maybe we could better help people.”

Syrian puppeteer Walid Abu Rashed performs a puppet act for children amid the rubble of damaged buildings in Syria's northwestern city of Saraqeb in the Idlib province on September 29, 2019. (AFP)

The epigenetic clock is a way of estimating a person’s biological age by looking at specific chemical changes in their DNA, rather than just counting the years since birth.

It works like a biological stopwatch that ticks based on how the body is aging at the cellular level — influenced by someone’s environment, lifestyle, including their general health, as well as stress levels.

The research also found that trauma caused a significant increase in “epigenetic ageing” in fetuses, which had “profound” health impacts on children.

“The women who were pregnant themselves who were directly exposed to the trauma did not have accelerated aging. Neither did their grandchildren. However, the child born to that mother did,” said Dajani.

“To us, this speaks to the sensitivity of the fetus in the uterus, the prenatal stage, when the fetus is actively dividing, and they are very sensitive to what the mother is exposed to.

“Now, think of the impact of that on future generations? Because if you consider the thousands of women pregnant in Gaza during the last two years, what does that mean for that generation born of mothers who experienced it all?”

Caption

A separate study identified another notable impact that trauma in conflict appears to be having on child development.

Syrian children displaced to Lebanon who had lived experience of trauma appeared to be suffering stunted or slowed rates of biological aging.

“What we found is that the biological age of the children that experienced war was a little bit delayed compared to their chronological age,” Michael Pluess, a professor of developmental psychology at the UK’s University of Surrey, told Arab News.

“This is not where we expected to find. You would expect to find that the aging would have been accelerated, which is what we usually find in adults. If they experience stress, they age more quickly than their chronological age, which basically means it’s a decline in cognitive ability.

“But for children who are still developing, it seems to stunt that development and delay it.”

Pluess says more research is needed to fully establish the correlation, but said it appears that changes in genomes are more sensitive during developmental stages. Given that Gaza has such a young population, the impact of the war could be profound.

With researchers continuing to learn more about the human genome, Mulligan says she remains optimistic that epigenetic changes brought on by trauma in conflict can be undone.

Palestinian children inspect the debris of a damaged building belonging to the Ministry of Religious Endowments, which was sheltering displaced people in the Zeitoun neighborhood of Gaza City on November 20, 2025, a day after it was targeted by Israeli army. (AFP)

“If they can change because of a bad exposure, it makes sense that they could change because of a good or corrective exposure,” she said. “We just need to figure out what those corrective interventions might be.”

For Dajani, the solution to such a complex issue lies in human traditions rather than the laboratory.

“We have survived as a species for three reasons, not just because we’re smart — it’s because we have agency,” she said. “We can adapt and resist. It’s because we are social and can depend on each other. And it’s because we have faith.”

She rejected many of the "well-intentioned" solutions posited by Western aid agencies to help solve issues that she instead believes require communal and spiritual answers.

“The sterilization of the international community and science has denied us this trait which allowed us to survive as a species,” she said.

Solutions developed for Gaza going forward should be based on responses that are organic to the people of Gaza, that do not treat them as victims, but instead allow them to begin to heal in a way that is natural and sovereign to them.