LONDON: Among the fans of the British crime writer Agatha Christie, it’s no secret that the literary mother of such enduring fictional characters as Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot loved Iraq and, for some years after the Second World War, lived in a house in Baghdad.

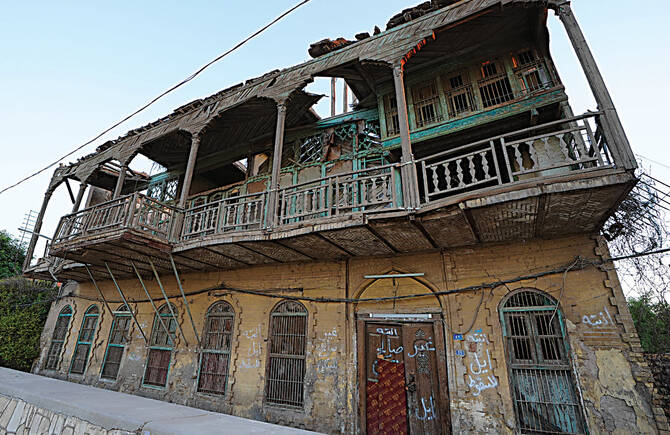

According to recent reports originating from Turkiye’s Anadolu Agency, that house, in the city’s Karrada Maryam district on the west bank of the Tigris, is now a near-ruin, in danger of imminent collapse.

As the story goes, it isn’t only Christie’s association with the property that makes it a heritage gem worth saving for posterity.

Known as the Beit Melek Ali, legend has it that the house once belonged to Ali bin Hussein, the former King of Hejaz who sought sanctuary in Baghdad after being deposed in 1925.

English detective novelist, Agatha Christie (1890-1976) typing at her home, Greenway House, Devon, January 1946. (Getty Images/AFP File)

But there’s a problem with this narrative, which is somewhat undermined by a mystery that Christie herself might have relished, and to which she left few clues behind.

It is clear from recently published photographs of the house in the city’s Karrada Maryam district, on the riverbank in the shadow of Al-Jumariyah bridge and close to the northerly edge of the Green Zone, that this abandoned building is indeed in an advanced state of disrepair. Most of its roof is missing and its river-facing balconies are sagging.

But did Christie ever really stay here and, if so, when, exactly?

The author first came to Baghdad in 1928, at the age of 38, in the wake of her much-publicised divorce from her first husband, Col. Archibald Christie, whom she had married in 1914.

She travelled from England in style, as far as Istanbul on board the luxurious Orient Express — a journey that inspired her 1934 novel, “Murder on the Orient Express” — and from there on to Baghdad, via another train to Damascus and from there across 880 km of desert by a specially equipped car, part of a fleet operated on the route by the Nairn Transport Company, which was run by two New Zealand brothers.

Cover of Agatha Christie’s “Murder on the Orient Express” book.

The 48-hour journey, as Christie recalled in her autobiography, was “fascinating and rather sinister,” broken by an overnight stay at a well-guarded fort in the isolated town of Rutbah in western Iraq, midway between Damascus and Baghdad.

Christie described her first sight of Baghdad: “In the distance, on the left, we saw the golden domes of Kadhimain, then on and over another bridge of boats, over the river Tigris, and so into Baghdad — along a street full of rickety buildings, with a beautiful mosque with turquoise domes standing, it seemed to me, in the middle of the street.”

On this occasion she stayed with one of the many expat British couples based in Baghdad. The capital had been seized from Ottoman forces in 1917 and, like the rest of the country, would remain under British control until Iraq was granted independence in 1932.

English detective novelist, Agatha Christie (1890 - 1976), circa 1950. (ullstein bild via Getty Images)

At that time, as Christie’s biographer Laura Thompson wrote, Baghdad “was a city where the British traveller could find racing, tennis, clubs and no doubt Marmite on toast; in the pre-war years it was not at all unusual to find people of Agatha’s class in such places.”

Christie embarked on the obligatory round of social calls, during which she met the famous archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley, who in 1922 had begun excavating the ancient Sumerian royal city of Ur. Christie became friends with Woolley and his wife, Katherine, and was invited to the dig, 300 km southeast of Baghdad.

Christie returned to England, but came back to Baghdad, and to Ur, in 1930. On this trip she met her future husband, Woolley’s assistant Max Mallowan, and they were married in September that year.

'Modern Baghdad, the City of Caliphs', Iraq 1925. A print from Baghdad, Camera Studio Iraq, published by Hasso Bros, Rotophot AG, Berlin, 1925. (Print Collector photo/Getty Images)

From 1930 to 1939, and then again — after the Second World War — from 1949 to the late 1950s, Christie accompanied Mallowan on an estimated 15 or more archaeological digs in Iraq or Syria, frequently staying in Baghdad en route.

However, in her autobiography, begun in 1950 and completed in 1965, only once did Christie mention living in Baghdad.

“I have not yet mentioned our house in Baghdad,” she writes near the end of the book, which was published posthumously in 1977, the year after her death.

“We had an old Turkish house on the West bank of the Tigris. It was thought a very curious taste on our part to be so fond of it, and not to want one of the modern boxes, but our Turkish house was cool and delightful, with its courtyard and the palm-trees coming up to the balcony rail.”

This, possibly, was the house that now stands derelict on the Tigris. But there is evidence that after the war Christie and her husband moved into a far grander property in Baghdad.

An Agatha Christie fan site repeats the story that “Christie lived in the Beit Melek Ali with Max Mallowan for a time.” In 1949, it adds, the Iraqi-Palestinian author Jabra Ibrahim Jabra wrote of meeting the Mallowans there.

Robert Hamilton, an archaeologist who invited Jabra to meet the Mallowans, told him it was “the house of King Ali ... an old Turkish house that goes back to the Ottoman period, and it is one of the most beautiful homes of old Baghdad.”

Ashar Creek leading to the Shatt al-Arab, Basra, Iraq, 1925. (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

But even in its heyday, the house now decaying on the river’s edge in the Karradat Maryam neighborhood would not have fitted that description.

King Ali of the Hejaz had fled to Baghdad in 1925 because his brother Faisal had been installed as King of Iraq four years earlier. Ali died in Baghdad in 1935 and Christie, whose first trip to Baghdad was in 1928, seven years before the exiled king died, was certainly aware of the house where he lived.

She set two books in Iraq: Murder in Mesopotamia, inspired by her archaeological adventures and published in 1936, and the 1951 adventure They Came to Baghdad.

In this spy thriller a character is told to walk along the Tigris until she comes to the Beit Melek Ali. She finds “a big house built right out on to the river with a garden and balustrade. The path on the bank passed on the inside of what must be the Beit Melek Ali or the House of King Ali. She could not go along the bank any further and so turned inland.”

This description fits the only known photograph of the Beit Melek Ali, held in the archives of the US Library of Congress. Unlike the altogether less impressive house by Jumariyah bridge, this building — far grander, and clearly fit for a king — is right on the waterfront, with no path in front of it.

It seems improbable that in her autobiography Christie would have made no mention of the history of her Baghdad house had she in fact lived in the Beit Melek Ali — and, besides, there are other candidates for the title “Agatha Christie’s Baghdad house.”

This photo taken on June 5, 1957, shows an excavation site of an ancient Assyrian Fortress built more than 25 centuries ago, at Nimrud, in what is now Iraq. British Archeologist M.E. Mallowan, aided by his wife, mystery story writer Agatha Christie, supervised the excavation. (Getty Images)

Mallowan, her husband, was a member of an organization called the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, which in 1946 purchased a building in Baghdad. As a paper published in 2018 in the journal of the American Society of Overseas Research recalled, Mallowan was appointed as the school’s first director “and immediately took up residence, along with a secretary, six students and Agatha Christie.”

This, then, was Christie’s house in Baghdad during the 1940s and 1950s. There is an oblique reference to it in her obituary, published in 1976 in the British School of Archaeology’s journal Iraq, which recorded only that “in the old schoolhouse overlooking the river Tigris in Baghdad where she wrote ‘They Came to Baghdad,’ she would read and write in peace.”

But where it was, and whether it is still standing today — questions that can also be asked of the true Beit Melek Ali — remains a mystery.

READ MORE:

• Agatha Christie and her Middle Eastern mysteries

• Agatha Christie had little-known role in ancient Nimrud

The likelihood that the now-decrepit old house by Al-Jumariyah bridge was the headquarters of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, and the home for several years of Christie and Mallowan, is further undermined by two photographs, both of which purport to show Christie on the balcony of the BSAI, and neither of which appears to have been taken at the claimed Christie house in the Karrada Maryam district.

In terms of pinpointing the exact location of the BSAI house she shared with Mallowan in Baghdad, inquiries with both the organization (which in 2007 was renamed The British Institute for the Study of Iraq) and the Christie Archive Trust have so far drawn a blank.

Meanwhile, an email this week from an archaeologist who has written about the history of the BSAI has muddied the waters further.

“As far as I know, there was nothing particularly special about the (BSAI) house,” Mary Shepperson, who specializes in the urban archaeology of the Middle East at the University of Liverpool’s School of Architecture, told Arab News.

“It was chosen because it was cheap -– archaeology always operates on a shoestring. It was notoriously basic. I think it’s still standing today but in very poor shape.”

Caption

And then she added: “I don’t think either of the two photos you sent are the old BSAI house.”

Attached to the email was a photograph of yet another building in Baghdad. “This,” Shepperson declared, “is a picture of the river side of the house.”

As Christie wrote in her very first detective novel, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles,” published in 1920, “everything must be taken into account. If the fact will not fit the theory — let the theory go.”

Ultimately, though, Christie, who died in 1976 at the age of 85, would probably have found the fascination with her living arrangements in Baghdad tedious.

“People,” as she once said, “should be interested in books, not their authors.”