BEIRUT: It’s as if the whole weight of Israel’s war in Gaza has fallen on Amr Al-Hams. The 3-year-old has shrapnel in his brain from an Israeli strike on his family’s tent. His pregnant mother was killed. His father is paralyzed by grief over the death of his longtime sweetheart.

Now the boy is lying in a hospital bed, unable to speak, unable to move, losing weight, while doctors don’t have the supplies to treat his brain damage or help in his rehabilitation after a weekslong blockade and constant bombardment.

Recently out of intensive care, Amr’s frail body twists in visible pain. His wide eyes dart around the room. His aunt is convinced he’s looking for his mother. He can’t speak, but she believes he is trying to say “mom.”

“I am trying as much as I can. It is difficult,” said his aunt Nour Al-Hams, his main caregiver, sitting next to him on the bed in Khan Younis’ Nasser Hospital in southern Gaza. “What he is living through is not easy.”

To reassure him, his aunt sometimes says his mother will be back soon. Other times, she tries to distract him, handing him a small ball.

The war has decimated the health system

The war began Oct. 7, 2023, when Hamas-led militants stormed into Israel and killed some 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and took 251 people captive. Israel’s retaliatory campaign has killed over 57,000 Palestinians, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry, which says women and children make up most of the dead but does not specify how many were fighters or civilians.

Nearly 21 months into the conflict that displaced the vast majority of Gaza’s 2.3 million people, it is nearly impossible for the critically wounded to get the care they need, doctors and aid workers say.

The health care sector has been decimated: Nearly half of the territory’s 36 hospitals have been put out of service. Daily bombings and strikes overwhelm the remaining facilities, which are operating only partially. They struggle with shortages of anything from fuel, gauze and sutures to respirators or scanners that have broken down and can’t be replaced.

Israeli forces have raided and besieged medical facilities, claiming Hamas militants have used them as command centers. Doctors have been killed or were displaced, unable to reach hospitals because of continued military operations.

For more than 2 1/2 months, Israel blocked all food, medicine and other supplies from entering Gaza, accusing Hamas of siphoning off aid to fund its military activities, though the UN said there was no systematic diversion. The population was pushed toward famine.

Since mid-May, Israel has allowed in a trickle of aid, including medical supplies.

Gaza’s Health Ministry estimates that 33,000 children have been injured during the war, including 5,000 requiring long-term rehabilitation and critical care. Over 1,000 children, like Amr, are suffering from brain or spinal injuries or amputated limbs.

“Gaza will be dealing with future generations of kids living with all sorts of disabilities, not just brain, but limb disabilities that are consequences of amputation that could have been prevented if the health system was not under the pressures it is under, wasn’t systematically targeted and destroyed as it was,” said Tanya Hajj-Hassan, a pediatric intensive care specialist who has volunteered multiple times in Gaza with international medical organizations.

A fateful journey north

In April, one week before her due date, Amr’s mother, Inas, persuaded her husband to visit her parents in northern Gaza. They trekked from the tent they lived in on Gaza’s southern coast to the tent where her parents live.

They were having an evening meal when the strike hit. Amr’s mother and her unborn baby, his grandfather and his brother and sister were killed.

Amr was rushed to the ICU at Indonesian Hospital, the largest in northern Gaza. A scan confirmed shrapnel in his brain and reduced brain function. A breathing tube was inserted into his throat.

“He is 3. Why should he bear the weight of a rocket?” his aunt asked.

His father, Mohammed, was too stunned to even visit the ICU. His wife had been the love of his life since childhood, the aunt said. He barely spoke.

Doctors said Amr needed advanced rehabilitation. But while he was at the hospital, Israeli forces attacked the facility — encircling its premises and causing damage to its communication towers, water supplies and one of its wards. Evacuation orders were issued for the area, and patients were transferred to Shifa Hospital in Gaza City.

Another treacherous journey

But Shifa was overwhelmed with mass casualties, and staff asked the family to take Amr south, even though no ambulances or oxygen tanks could be spared.

The father and aunt had to take Amr, fresh out of ICU with the tube in his throat, in a motorized rickshaw for the 25-kilometer (15-mile) drive to Nasser Hospital.

Amr was in pain, his oxygen levels dropped. He was in and out of consciousness. “We were reading the Qur’an all along the road,” said his aunt, praying they would survive the bombings and Amr the bumpy trip without medical care.

About halfway, an ambulance arrived. Amr made it to Nasser Hospital with oxygen blood levels so low he was again admitted to ICU.

Unable to get the care he needs

Still, Nasser Hospital could not provide Amr with everything he needed. Intravenous nutrients are not available, Nasser’s head of pediatrics, Dr. Ahmed Al-Farra, said. The fortified milk Amr needed disappeared from the market and the hospital after weeks of Israel’s blockade. He has lost about half his weight.

When he came out of the ICU, Nour shared his bed with him at night and administered his medication. She grinds rice or lentils into a paste to feed him through a syringe connected to his stomach.

“We have starvation in Gaza. There is nothing to eat,” said his aunt, who is a trained nurse. “There is nothing left.”

The care Amr has missed is likely to have long-term effects. Immediate care for brain injuries is critical, Hajj-Hassan said, as is follow-up physical and speech therapy.

Since the Israeli blockade on Gaza began in March, 317 patients, including 216 children, have left the territory for medical treatment alongside nearly 500 of their companions, according to the World Health Organization.

Over 10,000 people, including 2,500 children, await evacuation.

Amr is one of them.

COGAT, the Israeli military body in charge of civilian affairs in Gaza, coordinates medical evacuations after receiving requests from countries that will take the patients and security screenings. In recent weeks, over 2,000 patients and their companions have left for treatment, COGAT said, without specifying the time period.

Tess Ingram, spokesperson for the UN children’s agency, said the only hope for many critically injured who remain in Gaza is to get out. Countries need to “open their hearts, open their doors and open their hospitals to children who survived the unimaginable and are now languishing in pain,” she said.

Amr’s aunt reads his every move. He is unhappy with his diapers, she said. He outgrew them long ago. He was a smart kid, now he cries “feeling sorry for himself,” said Nour. He gets seizures and needs tranquilizers to sleep.

“His brain is still developing. What can they do for him? Will he be able to walk again?” Nour asked. “So long as he is in Gaza, there is no recovery for him.”

A boy in Gaza with brain damage fights for his life amid blockade

https://arab.news/zfpar

A boy in Gaza with brain damage fights for his life amid blockade

- Nearly 21 months into the conflict, it is nearly impossible for the critically wounded to get the care they need, doctors and aid workers say

- Since the Israeli blockade on Gaza began in March, 317 patients, including 216 children, have left the territory for medical treatment alongside nearly 500 of their companions, according to the World Health Organization

How growing public support to disarm Hezbollah is forcing a reckoning in Lebanon

- Polling suggests broad public backing for Hezbollah disarmament, reflecting fatigue with perpetual war and instability

- Many supporters remain wary, fearing loss of protection amid Israeli strikes and doubts over Lebanese army’s abilities

DUBAI: Lebanon’s government recently instructed the army to prepare a plan to disarm all armed factions and restore the state’s monopoly on weapons. It was widely interpreted as a move to disarm Hezbollah.

However, despite international calls for Hezbollah to surrender what remains of its heavy arsenal, the move has triggered a political tit-for-tat that now threatens to plunge the country into a new civil war.

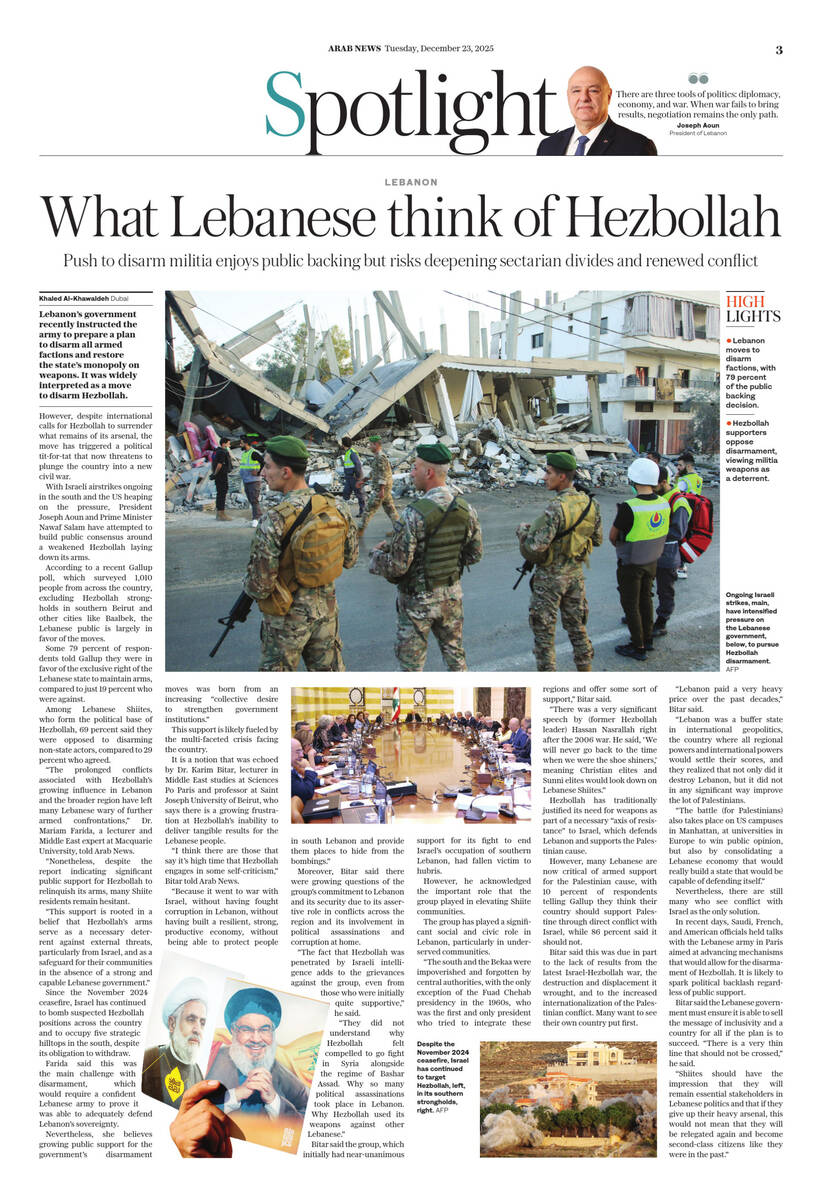

With Israeli airstrikes ongoing in the south and the US heaping on the pressure, President Joseph Aoun and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam have attempted to build public consensus around a weakened Hezbollah laying down its arms.

According to a recent Gallup poll, which surveyed a random sample of 1,010 people from across the country, excluding Hezbollah strongholds in southern Beirut and other cities like Baalbek, the Lebanese public is largely in favor of the moves.

Some 79 percent of respondents told Gallup they were in favor of the exclusive right of the Lebanese state to maintain arms, compared to just 19 percent who were against.

Among Lebanese Shiites, who form the political base of Hezbollah, 69 percent said they were opposed to disarming non-state actors, compared to 29 percent who agreed — underlining the fragmented nature of Lebanese society and politics.

“The prolonged conflicts associated with Hezbollah’s growing influence in Lebanon and the broader region have left many Lebanese wary of further armed confrontations,” Dr. Mariam Farida, a lecturer and Middle East expert at Macquarie University, told Arab News.

“Nonetheless, despite the report indicating significant public support for Hezbollah to relinquish its arms, many Shiite residents remain hesitant.

“This support is rooted in a belief that Hezbollah’s arms serve as a necessary deterrent against external threats, particularly from Israel, and as a safeguard for their communities in the absence of a strong and capable Lebanese government.”

Since the November 2024 ceasefire, Israel has continued to bomb suspected Hezbollah positions across the country and to occupy five strategic hilltops in the south, despite its obligation to withdraw.

Farida said this was the main challenge with disarmament, which would require a confident Lebanese army to prove it was able to adequately defend Lebanon’s sovereignty.

Nevertheless, she believes growing public support for the government’s disarmament moves was born from an increasing “collective desire to strengthen government institutions.”

This support is likely fueled by the multi-faceted crisis facing the country, which the International Monetary Fund characterizes as a severe, “man‑made” depression caused by years of mismanagement, corruption, weak governance, and an unsustainable economic model.

It is a notion that was echoed by Dr. Karim Bitar, lecturer in Middle East studies at Sciences Po Paris and professor at Saint Joseph University of Beirut, who says there is a growing frustration at Hezbollah’s inability to deliver tangible results for the Lebanese people.

“I think there are those that say it’s high time that Hezbollah engages in some self-criticism,” Bitar told Arab news.

“Because it went to war with Israel, without having fought corruption in Lebanon, without having built a resilient, strong, productive economy, without being able to protect people in south Lebanon and provide them places to hide from the bombings.”

Moreover, Bitar said there were growing questions of the group’s commitment to Lebanon and its security due to its assertive role in conflicts across the region and its involvement in political assassinations and corruption at home.

“The fact that Hezbollah was penetrated by Israeli intelligence adds to the grievances against the group, even from those who were initially quite supportive,” he said.

“They did not understand why Hezbollah felt compelled to go fight in Syria alongside the regime of Bashar Assad. Why so many political assassinations took place in Lebanon. Why Hezbollah used its weapons against other Lebanese.”

Bitar said the group, which initially had near-unanimous support for its fight to end Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon, had over the years fallen victim to hubris, which had led to its downfall.

However, he acknowledged the important role that the group played in elevating Shiite communities, which had historically been disenfranchised.

Over the years, the group has played a significant social and civic role in Lebanon, particularly in underserved communities where state services are weak or absent.

Through its network of charities and social institutions, it runs hospitals, clinics, schools, and food assistance programs that provide healthcare, education, and basic support to thousands of families.

“The south and the Bekaa were impoverished and forgotten by central authorities, with the only exception of the Fuad Chehab presidency in the 1960s, who was the first and only president who tried to integrate these regions and offer some sort of support,” Bitar said.

“There was a very significant speech by (former Hezbollah leader) Hassan Nasrallah right after the 2006 war. He said, ‘We will never go back to the time when we were the shoe shiners,’ meaning Christian elites and Sunni elites would look down on Lebanese Shiites.”

Hezbollah has traditionally justified its need for weapons as part of a necessary “axis of resistance” to Israel, which defends Lebanon and supports the Palestinian cause.

However, many Lebanese are now critical of armed support for the Palestinian cause, with 10 percent of respondents telling Gallup they think their country should support Palestine through direct conflict with Israel, while 86 percent said it should not.

Bitar said this was due in part to the lack of results from the latest Israel-Hezbollah war, the destruction and displacement it wrought upon Lebanon, and to the increased internationalization of the Palestinian conflict. Many want to see their own country put first.

“Lebanon paid a very heavy price over the past decades,” Bitar said.

“Lebanon was a buffer state in international geopolitics, the country where all regional powers and international powers would settle their scores, and they realized that not only did it destroy Lebanon, but it did not in any significant way improve the lot of Palestinians.

“The battle (for Palestinians) also takes place on US campuses in Manhattan, at universities in Europe to win public opinion, but also by consolidating a Lebanese economy that would really build a state that would be capable of defending itself.”

Nevertheless, there are still many who see armed conflict with Israel as the only solution.

In recent days, Saudi, French, and American officials held talks with the Lebanese army in Paris aimed at advancing mechanisms that would allow for the disarmament of Hezbollah. It is a controversial move that is likely to spark political backlash regardless of public support.

Bitar said the Lebanese government must ensure it is able to sell the message of inclusivity and a country for all if the plan is to succeed. “There is a very thin line that should not be crossed,” he said.

“Shiites should have the impression that they will remain essential stakeholders in Lebanese politics and that if they give up their heavy arsenal, this would not mean that they will be relegated again and become second-class citizens like they were in the past.”