AHMEDABAD: Huddled over piles of colorful paper, Mohammad Yunus is one among thousands of workers in India’s western state of Gujarat who make kites by hand that are used during a major harvest festival.

People in Gujarat celebrate Uttarayan, a Hindu festival in mid-January that celebrates the end of winter by flying kites held by glass-coated or plastic strings.

“The kite may seem like a small item but it takes a long time to make it. Many people are involved in it and their livelihoods depend on it,” Yunus, a Muslim who comes to Gujarat from neighboring Rajasthan state to make kites during the peak season, told Reuters.

Kite enthusiasts fly kites during the eight-day-long International Kite Festival in Ahmedabad, India, on January 7, 2024. (REUTERS)

More than 130,000 people are involved in kite-making throughout Gujarat, according to government estimates, many of whom work from homes to make kites that cost as little as five rupees (6 US cents).

At the start of the two-day festival, people rent roofs and terraces from those who have access to them, and gather there to fly colorful kites that criss-cross each other in the sky.

Gujarat is a hub of the kite industry in the country, boasting a market worth 6.50 billion Indian rupees ($76.58 million), and the state accounts for about 65 percent of the total number of kites made in India.

A woman makes kites inside her house in Ahmedabad, India, on October 10, 2024. (REUTERS)

While the kite flying season in the state is limited to almost just 2 or 3 days in January, the industry runs year-round providing employment to about 130,000 people in the state, according to government figures.

But these paper birds are also harmful and can be fatal, especially kites that have plastic strings, which can cause serious cuts to birds in the sky, killing and injuring thousands of them during the festival.

At least 18 people died from kite related injures across Gujarat during this year’s Uttarayan festival, including being cut by a string and getting electrocuted while trying to extricate a kite from an electric pole, local media reported.

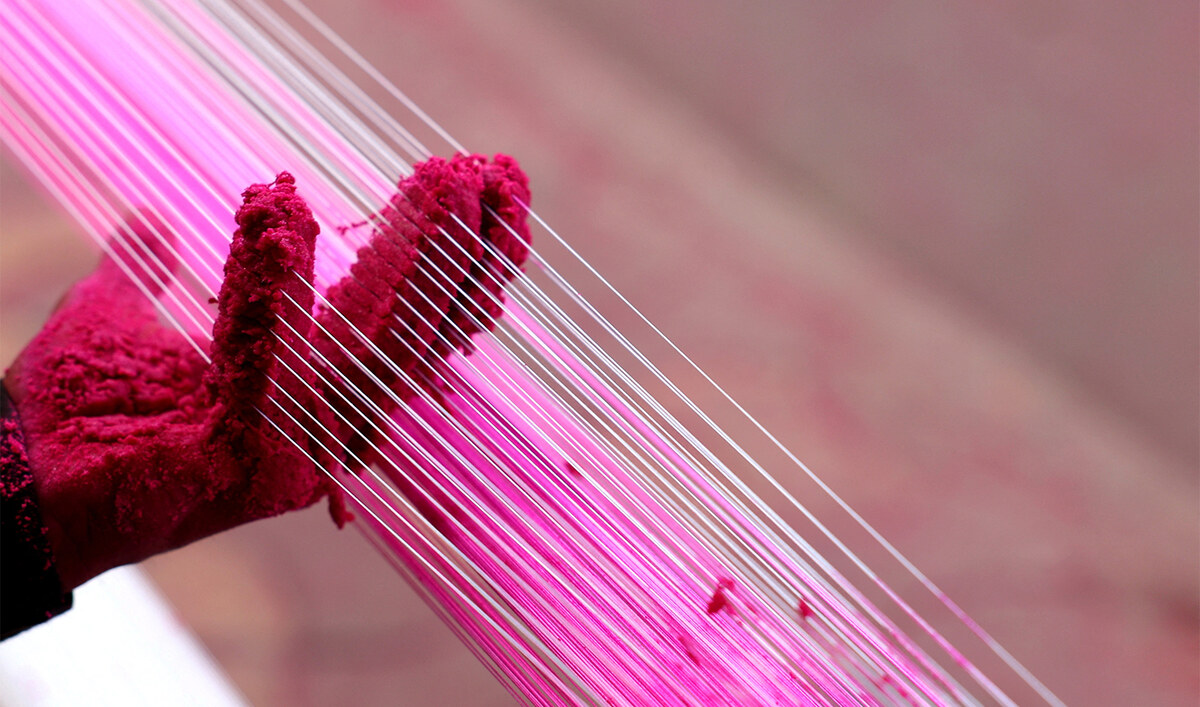

A worker applies colour to strings which will be used to fly kites, at a roadside kite market in Ahmedabad, India, on December 31, 2023. (REUTERS)