ISTANBUL: A Turkish government proposal to end a decades-long conflict with Kurdish militants has put Kurdish rights back in the spotlight, at a time when Kurdish leaders say repression is rife and freedoms won more than a decade ago have eroded.

One of those is the right to receive two hours of Kurdish language education in school, a move introduced by Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan in 2012 as an “historic step” in a country which once banned the Kurdish language outright.

More than a dozen parents, Kurdish politicians and education experts told Reuters their children today could not receive the language classes even in Turkiye’s largest cities, and not all Kurdish families knew of the right to ask for them.

Turkiye’s Kurds make up about a fifth of the population, numbering an estimated 17 million. Kurdish is the mother tongue for most and the right to education in Kurdish is one of their main demands.

The constitution however states, “no language other than Turkish shall be taught as mother tongue to Turkish citizens.”

“The Kurdish people’s right to education in their mother tongue is essential for the expression of their cultural identity and social equality,” said Gulistan Kilic Kocyigit, chairperson of the pro-Kurdish DEM party in parliament.

“Education in mother tongue is essential for peace, equal citizenship and the protection of cultural rights.”

Erdogan’s key ally in his ruling alliance made a shock proposal in October that jailed Kurdish militant PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan end his group’s insurgency in exchange for the possibility of his release.

Previously, a peace process with the militants was started in 2012 but collapsed in 2015 and was followed by fresh violence and a crackdown on the pro-Kurdish political movement.

“Optional Kurdish classes have become invisible in schools since the end of the peace process,” said Remezan Alan, a lecturer within the Kurdish Language and Culture department of Artuklu University in Turkiye’s southeastern Mardin province. The department was formed in 2009.

Two of Alan’s children were unable to access Kurdish class in Diyarbakir, a city of 1.8 million in the mainly Kurdish southeast. “There were enough requests, but a teacher was not available,” he said.

Asked about the classes, Turkiye’s ministry of education, which speaks for schools, said, “it is possible for a course to be taught if at least 10 students are enrolled.” It did not comment on the situation in individual schools.

Education Minister Yusuf Tekin last month denied that the state was ignoring requests from parents for the lessons or discouraging them from asking for them. If there were not enough students he said, it was because of a 2012 boycott of the lessons by DEM’s predecessor party, which said two hours were not enough.

Parents want children to learn Kurdish in school so they can read and write in the language, they say.

Hudai Morarslan, a member of teachers’ union Egitim-Bir-Sen which campaigns for teachers’ rights and educational rights, says pupils have access to optional Kurdish classes in only 13 cities across Turkiye. He is campaigning for them to be available in Bingol, a town in the mainly Kurdish southeast region.

“Everyone is afraid to ask,” he said, adding that there is a constant fear of being stigmatized by the state and linked to the PKK, designated as a terrorist group by Turkiye, the United States and the European Union.

In November, Turkish authorities detained 231 people and replaced six pro-Kurdish mayors over suspected PKK ties. The DEM Party said those detained included its local officials and activists.

Earlier, dozens of people singing and dancing to Kurdish songs at weddings were detained on charges of “spreading terrorist propaganda,” which the DEM party said showed “intolerance toward Kurdish identity and culture.”

Government officials said the songs were an expression of solidarity with the PKK and a threat to national unity.

SLOW PROGRESS

Turkiye’s ban on the Kurdish language was lifted in 1991. Seventeen years later, state broadcaster TRT began a Kurdish TV channel, which some Kurds boycotted and criticized as government propaganda.

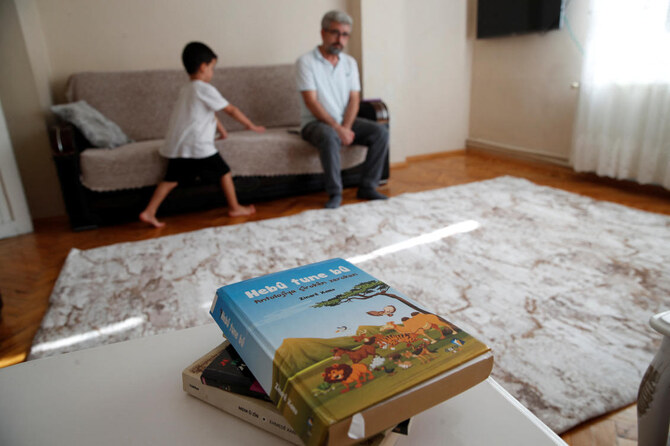

Nevzat Yesilbagdan, 43, lives in Istanbul’s Bagcilar district with his family. He says three of his children’s requests to learn Kurdish have been denied by the school due to a lack of teachers or an insufficient number of students.

“Our main demand is to be educated in our mother tongue, but an optional course is an important step toward that goal.”

A study released by Rawest Research, a think tank focused on Kurdish issues, found in 2020 that only 30 percent of some 1,500 parents were aware of the optional Kurdish courses.

Ihsan Yildiz, 42, who works in the construction sector in Istanbul, said his 15-year-old daughter Meryem received no response to her request for Kurdish class from her Islamic Imam Hatip school. She then stopped asking.

His children understand some Kurdish but can’t read it.

“My mother who lives with us does not speak Turkish. I translate when my children talk to their grandmother. This is so sad.”