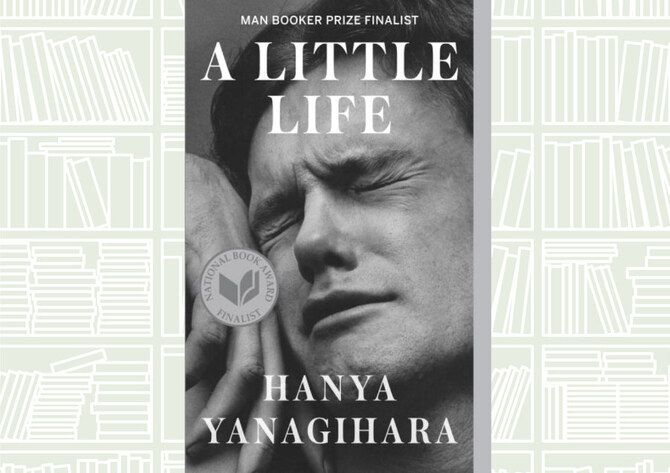

Hanya Yanagihara’s “A Little Life,” originally published in 2015, is a monumental and devastating exploration of trauma, friendship and the complexities of human resilience.

Spanning more than 700 pages, the novel is an emotionally intense journey that delves deep into the lives of four college friends as they navigate adulthood in New York City.

At its core, however, the novel revolves around Jude St. Francis, a character whose harrowing past and enduring pain form the emotional backbone of the story.

The power of “A Little Life” lies in its unflinching portrayal of suffering. Yanagihara masterfully crafts a narrative that is both intimate and unrelenting, capturing the profound impact of Jude’s traumatic experiences. His past, gradually revealed through the novel, casts a long shadow over his present, affecting not only his relationship with himself but also with those who care for him.

The depiction of trauma is raw and visceral, leaving a lasting impression on the reader. Yanagihara does not spare the reader from the depths of Jude’s anguish, making the novel a challenging but profoundly moving experience.

While the novel is heavy with themes of pain and loss, it also explores the transformative power of friendship. The bond between Jude and his friends — Willem, Malcolm and JB — offers moments of tenderness and connection that provide respite from the overwhelming darkness. Yanagihara’s portrayal of these relationships is one of the novel’s strengths, offering a nuanced look at love, loyalty and the ways in which friends become chosen family.

The deep emotional ties between the characters elevate “A Little Life” beyond a mere tale of suffering, making it a meditation on the capacity for human connection to heal, even when the scars run deep.

Yanagihara’s prose is haunting and beautiful, drawing the reader into the lives of the characters with an intensity that is hard to resist. The novel’s length allows for a thorough and immersive exploration of the characters’ inner worlds, making their joys and sorrows feel deeply personal.

Yet, “A Little Life” is not without its challenges. Its relentless focus on Jude’s trauma can be overwhelming, and the novel’s unremitting sadness may prove too intense for some readers. However, for those willing to confront its emotional weight, the novel offers a deeply affecting and unforgettable experience.

In “A Little Life,” Yanagihara examines the extremes of human experience — both the agonizing depths of despair and the redemptive potential of love. It is a novel that demands patience and emotional endurance but rewards readers with a story of profound emotional depth.

Although it may not be suitable for everyone, “A Little Life” is a masterpiece of modern literature, providing an unflinching look at pain, survival and the bonds that sustain us.