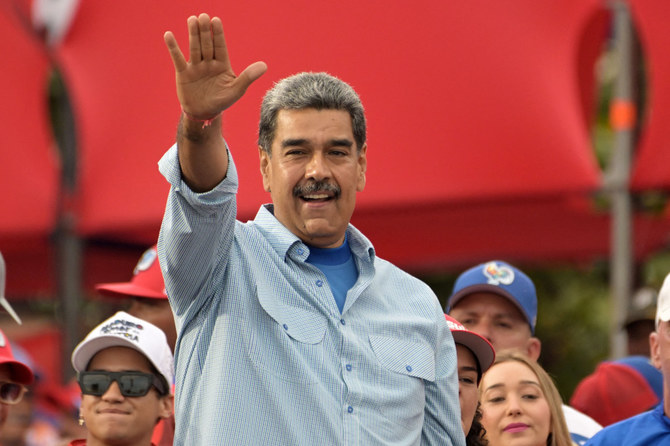

CARACAS, Venezuela: The future of Venezuela is on the line. Voters will decide Sunday whether to reelect President Nicolas Maduro, whose 11 years in office have been beset by crisis, or allow the opposition a chance to deliver on a promise to undo the ruling party’s policies that caused economic collapse and forced millions to emigrate.

Historically fractured opposition parties have coalesced behind a single candidate, giving the United Socialist Party of Venezuela its most serious electoral challenge in a presidential election in decades.

Maduro is being challenged by former diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia, who represents the resurgent opposition, and eight other candidates. Supporters of Maduro and Gonzalez marked the end of the official campaign season Thursday with massive demonstrations in the capital, Caracas.

Venezuelan opposition star Maria Corina Machado raises the hand of opposition presidential candidate Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia (L) in a show of support during a press conference in Caracas on July 25, 2024, ahead of Sunday's presidential election. (AFP)

Here are some reasons why the election matters to the world:

Migration impact

The election will impact migration flows regardless of the winner.

The instability in Venezuela for the past decade has pushed more than 7.7 million people to migrate, which the UN’s refugee agency describes as the largest exodus in Latin America’s recent history. Most Venezuelan migrants have settled in Latin America and the Caribbean, but they are increasingly setting their sights on the US.

A nationwide poll conducted in April by the Venezuela-based research firm Delphos indicated that about a quarter of the people in Venezuela were thinking about emigrating if Maduro wins again. Of those, about 47 percent said a win by the opposition would make them stay, but roughly the same amount indicated that an improved economy would keep them in their home country. The poll had a margin of error of plus or minus 2 percentage points.

The main opposition leader is not on the ballot

The most talked-about name in the race is not on the ballot: María Corina Machado. The former lawmaker emerged as an opposition star in 2023, filling the void left when a previous generation of opposition leaders fled into exile. Her principled attacks on government corruption and mismanagement rallied millions of Venezuelans to vote for her in the opposition’s October primary.

Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado greets supporters as she campaigns in support of former diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia in Caracas, Venezuela, on July 25, 2024. (REUTERS)

But Maduro’s government declared the primary illegal and opened criminal investigations against some of its organizers. Since then, it has issued warrants for several of Machado’s supporters and arrested some members of her staff, and the country’s top court affirmed a decision to keep her off the ballot.

Yet, she kept on campaigning, holding rallies nationwide and turning the ban on her candidacy into a symbol of the loss of rights and humiliations that many voters have felt for over a decade.

She has thrown her support behind Edmundo González Urrutia, a former ambassador who has never held public office, helping a fractious opposition unify.

They are campaigning together on the promise of economic reform that will lure back the millions of people who have migrated since Maduro became president in 2013.

González began his diplomatic career as an aide to Venezuela’s ambassador in the US in the late 1970s. He was posted to Belgium and El Salvador, and served as Caracas’ ambassador to Algeria. His last post was as ambassador to Argentina during Hugo Chávez’s presidency, which began in 1999.

Why is the current president struggling?

Maduro’s popularity has dwindled due to an economic crisis caused by a drop in oil prices, corruption and government mismanagement.

Maduro can still bank on a cadre of die-hard believers, known as Chavistas, including millions of public employees and others whose businesses or employment depend on the state. But the ability of his party to use access to social programs to make people vote has diminished as the economy has frayed.

He is the heir to Hugo Chávez, a popular socialist who expanded Venezuela’s welfare state while locking horns with the United States.

Sick with cancer, Chávez handpicked Maduro to act as interim president upon his death. He took on the role in March 2013, and the following month, he narrowly won the presidential election triggered by his mentor’s death.

Maduro was reelected in 2018, in a contest that was widely considered a sham. His government banned Venezuela’s most popular opposition parties and politicians from participating and, lacking a level playing field, the opposition urged voters to boycott the election.

That authoritarian tilt was part of the rationale the US used to impose economic sanctions that crippled the country’s crucial oil industry.

Mismanaged oil industry

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven crude reserves, but its production declined over several years, in part because of government mismanagement and widespread corruption in the state-owned oil company.

In April, Venezuela’s government announced the arrest of Tareck El Aissami, the once-powerful oil minister and a Maduro ally, over an alleged scheme through which hundreds of millions of dollars in oil proceeds seemingly disappeared.

That same month, the US government reimposed sanctions on Venezuela’s energy sector, after Maduro and his allies used the ruling party’s total control over Venezuela’s institutions to undermine an agreement to allow free elections. Among those actions, they blocked Machado from registering as a presidential candidate and arrested and persecuted members of her team.

The sanctions make it illegal for US companies to do business with state-run Petróleos de Venezuela S.A., better known as PDVSA, without prior authorization from the US Treasury Department. The outcome of the election could decide whether those sanctions remain in place.

An uneven playing field

A more free and fair presidential election seemed like a possibility last year, when Maduro’s government agreed to work with the US-backed Unitary Platform coalition to improve electoral conditions in October 2023. An accord on election conditions earned Maduro’s government broad relief from the US economic sanctions on its state-run oil, gas and mining sectors.

But days later, authorities branded the opposition’s primary illegal and began issuing warrants and arresting human rights defenders, journalists and opposition members.

A UN-backed panel investigating human rights violations in Venezuela has reported that the government has increased repression of critics and opponents ahead of the election, subjecting targets to detention, surveillance, threats, defamatory campaigns and arbitrary criminal proceedings.

The government has also used its control of media outlets, the country’s fuel supply, electric network and other infrastructure to limit the reach of the Machado-González campaign.

The mounting actions taken against the opposition prompted the Biden administration earlier this year to end the sanctions relief it granted in October.