RAWALPINDI: For Kishwar Naheed, one of Pakistan’s greatest living Urdu poets and writers, visiting the hundreds of book stalls stretched along Rawalpindi’s main Saddar market was once a usual Sunday morning activity.

But as the stalls have dwindled and book hawkers have disappeared, Naheed and others like her have been left only with the memories and a deep sense of loss over a disappearing literary culture and what was once the center of Rawalpindi’s intellectual life.

“Every Sunday morning, Zahid Dar [Urdu poet], Intizar [Hussain] Saab [novelist], myself, all my writer friends, we used to go there [Rawalpindi book bazaar] and try to pick up books,” Naheed told Arab News in an interview this week. “It was a craze for books.”

Rawalpindi’s open-air book stalls came up in the eighties and thrived until at least 2010 when the downfall slowly began, said Fareed-ul-Haq, a 69-year-old book stall owner.

“I’ve been selling books in this market for 25 years and this roadside book bazaar has been around for 50 years,” he told Arab News, saying people used to travel from other cities to visit the stalls, browsing for hours and often arriving with handwritten notes of titles they wanted.

“I have seen the high point of this market when the condition was such that it was so crowded it was difficult to walk here. Now people bring their books and it turns out they are their grandparents’ books and the grandson wants to sell them because he doesn’t value books.”

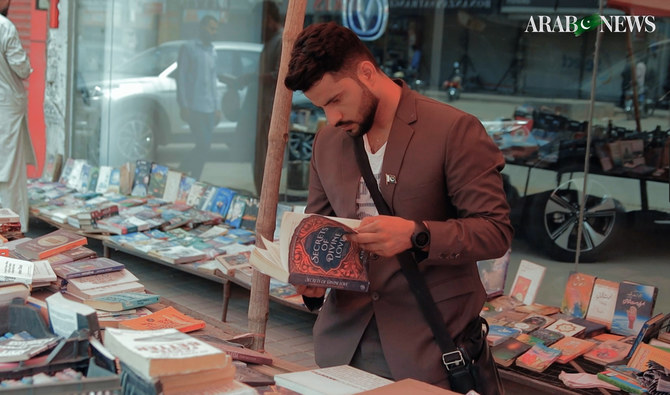

The roadside stalls offer a wide variety of new and old books: antique volumes, school books, historical works, fiction in different languages and all kinds of magazines.

But the rise of digital media and online bookstores has impacted the viability of book bazaars, sellers and customers said, with smartphones and social media causing a shift worldwide in how people consume information and read.

“We live in an era of social media, online and virtual books and many people don’t prefer reading physical books anymore,” Noaman Sami, a media sciences student at Rawalpindi’s Riphah International University, told Arab News.

Economic factors are also behind the decline in book bazaars, according to Muhammad Hameed Shahid, a Pakistani short story writer, novelist and literary critic.

Rising rents, inflation and the increasing cost of living had made it difficult for many booksellers to sustain their businesses, while customers had less money to spend on luxuries like books. Urban development projects have also displacd book bazaars as the literary corners are repurposed for commercial or residential development.

“Ordinary people often can’t afford expensive books, but at these roadside book stalls, you would find treasures,” Shahid said. “There’s a wide variety of books available, and these vendors sitting on our footpaths deserve support so that through them the flame of knowledge stays alive and books continue to reach our children.”

The bazaar, the writer said, had been a major player in his own literary journey:

“These vendors who used to be sitting on the footpaths with books spread around them, those books, covering all sorts of topics, they played a vital role in my career, they inspired me to become a writer.”

Future generations in Rawalpindi won’t get to experience this, Haq, the bookseller, lamented.

“I’ve seen this market crowded with people,” he said as he sat alone at his stall on a Sunday morning this month, waiting for customers. “But now, it’s nearly empty.”

The vanishing roadside book stalls of Rawalpindi

https://arab.news/cxsub

The vanishing roadside book stalls of Rawalpindi

- Roadside book bazaar along Rawalpindi’s main Saddar market came up in the eighties, thrived until at least 2010

- Rise of e-books has changed reading habits, economic factors and urban development have also impacted bazaars

Cairo book fair breaks visitor records

- Strong Saudi participation underscores KSA’s prominent role in Arab cultural landscape

- Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988, was selected as the fair’s featured personality

CAIRO: The 57th edition of the Cairo International Book Fair has attracted record public attendance, with the number of visits reaching nearly 6 million, up from a reported 5.5 million previously.

Egypt’s Minister of Culture Ahmed Fouad Hanou said: “This strong turnout reflects the public’s eagerness across all age groups to engage with the exhibition’s diverse cultural and intellectual offerings.”

Hanou said the event included “literary and intellectual activities, meetings with thinkers and creative figures, and thousands of titles spanning various fields of knowledge.”

The Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988, was selected as the fair’s featured personality, coinciding with the 20th anniversary of his death.

The exhibition’s official poster features a famous quote by Mahfouz: “Who stops reading for an hour falls centuries behind.”

A total of 1,457 publishing houses from 83 countries participated in the fair. Mahfouz’s novels occupied a special place, as Egypt’s Diwan Library showcased the author’s complete works, about 54 books.

“The pavilion of the Egyptian National Library and Archives witnessed exceptionally high attendance throughout the fair, showcasing a collection of rare and significant books.

Among the highlights was the book “Mosques of Egypt” in Arabic and English, Dr. Sherif Saleh, head of financial and administrative affairs at the Egyptian National Library and Archives, told Arab News.

The fair ended on Tuesday with a closing ceremony that featured a cultural performance titled “Here is Cairo.”

The event included the announcement of the winners of the fair’s awards, as well as the recipient of the Naguib Mahfouz Award for Arabic Fiction.

Organizers described this year’s edition as having a celebratory and cultural character, bringing together literature, art, and cinema.

Romania was the guest of honor this year, coinciding with the 120th anniversary of Egyptian-Romanian relations.

At the Saudi pavilion, visitors were welcomed with traditional coffee. It showcased diverse aspects of Saudi culture, offering a rich experience of the Kingdom’s heritage and creativity.

There was significant participation from Saudi Arabia at the event, highlighting the Kingdom’s prominent role in the Arab cultural arena.

Saudi Arabia’s participation aimed to showcase its literary and intellectual output, in alignment with the objectives of Vision 2030.

The Kingdom’s delegation was led by Saudi Arabia’s Ambassador to Egypt Saleh bin Eid Al-Hussaini. Also in attendance were Dr. Abdul Latif Abdulaziz Al-Wasel, CEO of the Literature, Publishing and Translation Commission, and Dr. Hilah Al-Khalaf, the commission’s director-general.

The King Abdulaziz Public Library placed the Encyclopedia of Saudi Arabia in a prominent position at the pavilion. The encyclopedia, consisting of 20 volumes, is organized according to the Kingdom’s culturally diverse regions.

Founded in 1980 by King Abdullah, the library was established to facilitate access to knowledge and preserve heritage collections. Over the years, it has grown into one of the Kingdom’s most important cultural institutions.

Internationally, the library has strengthened ties between Saudi Arabia and China, including the opening of a branch at Peking University and receiving the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Award for Cultural Cooperation between the two nations.

Regionally, the library has played a pivotal role in the Arab world through the creation of the Unified Arabic Cataloging Project, one of the most important initiatives contributing to knowledge accessibility and alignment with global standards.