OKUMA: Japan started releasing treated radioactive water from the wrecked Fukushima nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, a polarizing move that prompted China to announce an immediate blanket ban on all aquatic products from Japan.

China is “highly concerned about the risk of radioactive contamination brought by... Japan’s food and agricultural products,” the customs bureau said in a statement.

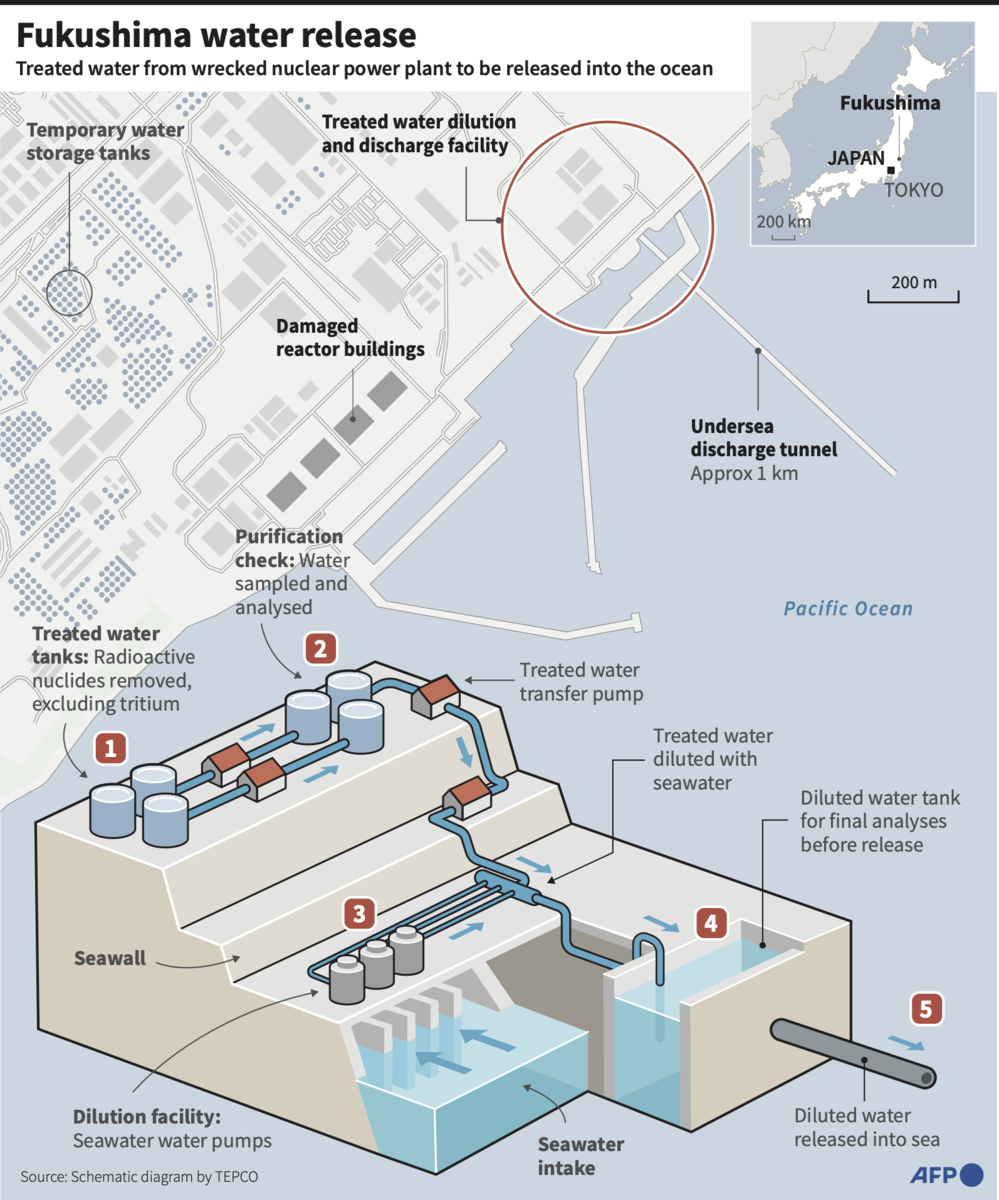

The Japanese government signed off on the plan two years ago and it was given a green light by the UN nuclear watchdog last month. The discharge is a key step in decommissioning the Fukushima Daiichi plant after it was destroyed by a tsunami in 2011.

Plant operator Tokyo Electric Power (Tepco) said the release began at 1:03 p.m. local time (0403 GMT) and it had not identified any abnormalities.

However, China reiterated its firm opposition to the plan and said the Japanese government had not proved that the water discharged would be safe.

“The Japanese side should not cause secondary harm to the local people and even the people of the world out of its own selfish interests,” its foreign ministry said in a statement.

Tokyo has in turn criticized China for spreading “scientifically unfounded claims.”

It maintains the water release is safe, noting that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has also concluded that the impact it would have on people and the environment was “negligible.”

Japan has requested that China immediately lift its import ban on aquatic products and seeks a discussion on the impact of the water release based on science, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida told reporters.

Japan exported about $600 million worth of aquatic products to China in 2022, making it the biggest market for Japanese exports, with Hong Kong second. Sales to China and Hong Kong accounted for 42 percent of all Japanese aquatic exports in 2022, according to government data.

China customs did not give details on the specific aquatic products impacted by the ban and did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

DECADES LONG PROCESS

The Fukushima Daiichi plant was destroyed in March 2011 after a massive 9.0 magnitude earthquake generated powerful tsunami waves causing meltdowns in three reactors.

The first discharge totalling 7,800 cubic meters — the equivalent of about three Olympic swimming pools of water — will take place over about 17 days.

According to Tepco test results released on Thursday, that water contained about up to 63 becquerels of tritium per liter, below the World Health Organization drinking water limit of 10,000 becquerels per liter. A becquerel is a unit of radioactivity.

The IAEA also released a statement saying its independent on-site analysis had confirmed the tritium concentration was far below the limit.

“There are not going to be any health effects… There is no scientific reason to ban imports of Japanese food whatsoever,” said Geraldine Thomas, former professor of molecular pathology at London’s Imperial College.

But Japanese fishing groups, hit with years of reputational damage from radiation fears, still oppose the plan.

“All we want is to be able to continue fishing,” the head of the Japan Fisheries Co-operative said in a statement that touched on the “mounting anxiety” of the community.

Separately from China, Hong Kong and Macau have announced their own ban starting Thursday, which covers Japanese seafood imports from 10 regions.

South Korean Prime Minister Han Duck-soo said import bans on Fukushima fisheries and food products will stay in place until public concerns were eased.

Japan will conduct monitoring around the water release area and publish results weekly starting on Sunday, Japan’s environment minister said. The release is estimated to take about 30 years.

PROTESTS

In Hong Kong, Jacay Shum, a 73-year-old activist, held up a picture portraying IAEA head Rafael Grossi as the devil.

“Japan’s actions in discharging contaminated water are very irresponsible, illegal, and immoral,” said Shum, who was among a group of about 100 marchers. “No one can prove that the nuclear waste and materials are safe. They are completely unsafe.”

South Korean police arrested at least 16 protesters who entered the Japanese embassy in Seoul, although South Korea’s government has said its own assessment found no problems with the scientific and technical aspects of the release.

North Korea’s foreign ministry demanded that the water discharge be immediately halted, calling it a “crime against humanity,” state media reported.

A few dozen protesters gathered in front of Tepco’s headquarters in Tokyo holding signs reading “Don’t throw contaminated water into the sea!“

“The Fukushima nuclear disaster is not over. This time only around 1 percent of the water will be released,” 71-year-old Jun Iizuka, who attended the protest, told Reuters. “From now on, we will keep fighting for a long time to stop the long-term discharge of contaminated water.”