RIYADH: The porticoes of the Grand Mosque in Makkah, with their Islamic architectural motifs and inscriptions of verses from the Qur’an, have a history that dates back to the time of Uthman bin Affan, the third caliph who led the Muslims after the death of the Prophet Muhammad.

Known as “riwaq” in the Arabic language, the porticoes or arcades are structures built as entrances that usually open into courtyards. The word “riwaq” was first used to refer to the structure that surrounds the circumambulation area of the Kaaba.

The porticoes surrounding the Holy Kaaba were not part of the original design.

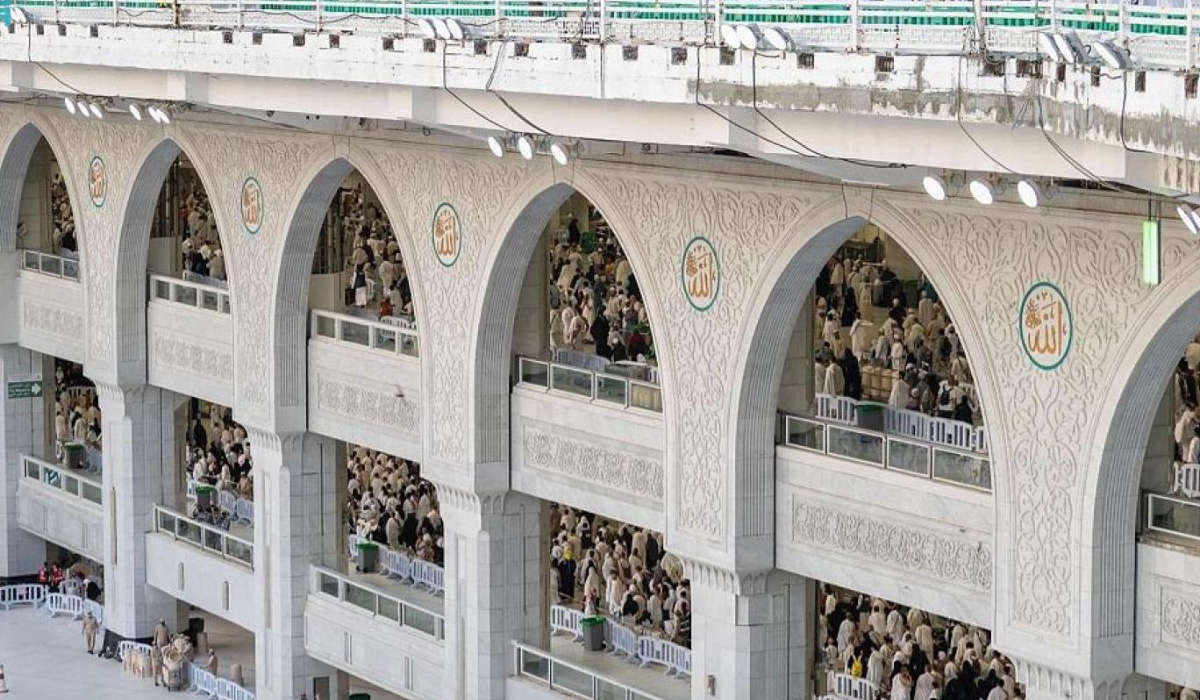

The Saudi portico provides a wider space for worshipers with its high-quality engineering standards. (SPA)

Fawaz bin Ali Al-Dahas, a former director general of the Makkah History Center, said: “Uthman bin Affan was the first to order the construction of a portico, and it was called the Ottoman portico.”

This was later expanded during the Abbasid caliphate in the 8th century. The modifications included the addition of elaborate mosaics and inscriptions that remain to this day.

There was no further expansion of the portico until the foundation of the Saudi state under King Abdulaziz.

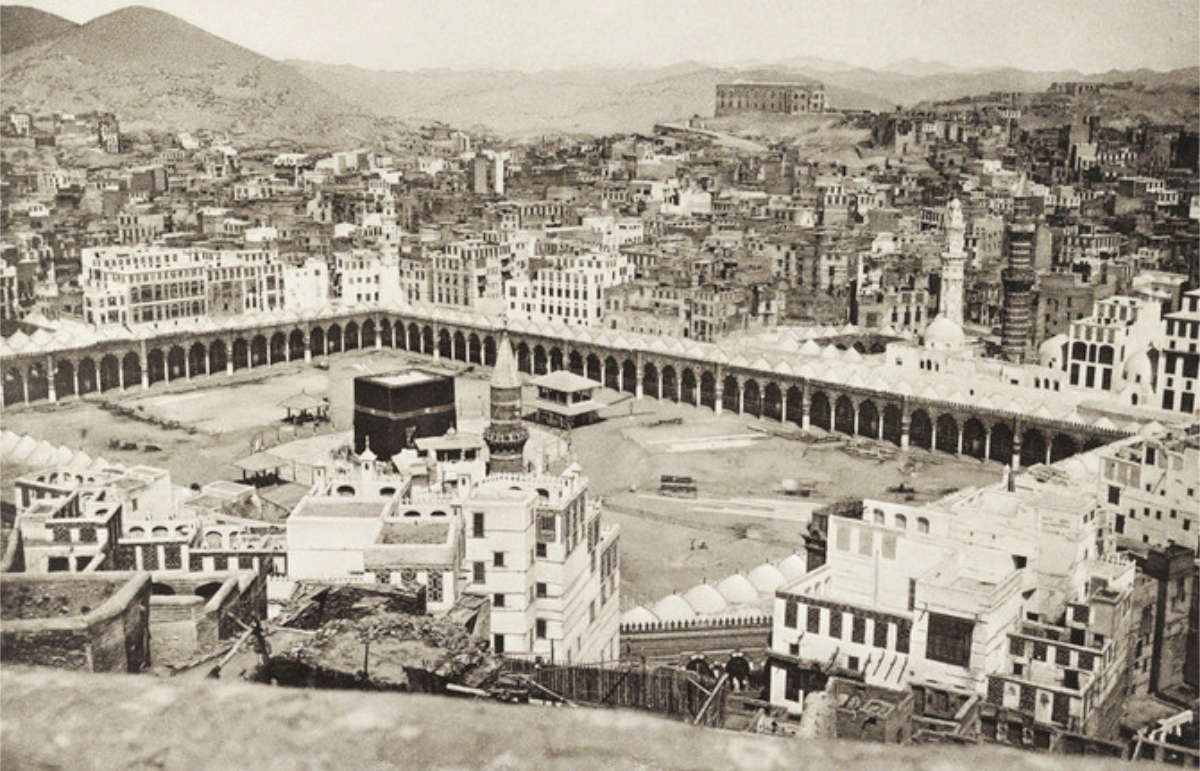

A view of how the portico looked like during the Abbasid caliphate. The picture was taken by the first Makkah photographer, Abdul Ghaffar. (Library of Congress photos)

“During King Abdulaziz’s reign, there was an expansion of the Prophet’s Mosque in Madinah, and the king wanted to do the same at the Grand Mosque in Makkah, but he died before that could happen,” Al-Dahas said.

The first Saudi expansion of the Grand Mosque happened during the reigns of King Saud, King Faisal and King Khalid, and included the reconstruction of the Ottoman portico.

The second Saudi expansion began in 1988, with King Fahd laying the foundation stone.

BACKGROUND

• The first Saudi expansion of the Grand Mosque happened during the reigns of King Saud, King Faisal and King Khalid, and included the reconstruction of the Ottoman portico.

• During King Abdullah’s reign, the Grand Mosque underwent the largest expansion in its history, increasing its total capacity and expanding the courtyard around the Kaaba.

During his reign, large courtyards surrounding the mosque were built and paved with heat-resistant marble. The Safa and Marwa area was expanded to facilitate the movement of those performing the Sa’ee — an integral part of the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage — and a bridge was built to connect the roof of the mosque to Al-Raquba area.

During King Abdullah’s reign, the Grand Mosque underwent the largest expansion in its history, increasing its total capacity and expanding the courtyard around the Kaaba.

King Salman has since launched five initiatives as part of a plan for the third Saudi expansion of the Grand Mosque. These include the expansion of the main building and courtyards, a pedestrian tunnel project and a central service station project.

As a result of the many expansion projects since the creation of the Saudi state, Abdulrahman Al-Sudais, president of the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques, announced in May that the Ottoman portico would be renamed the Saudi portico.

“The Saudi portico will be complementary to the Ottoman portico, with its distinction in a larger area that the Grand Mosque has never seen before,” Al-Sudais said.

The Saudi portico provides a wider space for worshipers with its high-quality engineering standards and is characterized by the availability of technical services, sound and lighting systems, and a faith-based environment for visitors to the mosque.