PARIS: Saudi Arabia’s location as a “bridge connecting north, south, east and west” means it could host a “truly inclusive” World Expo, Prince Faisal bin Farhan, the Saudi foreign minister, told the 172nd General Assembly of the Bureau International des Expositions in Paris on Tuesday.

Speaking as part of a high-level Saudi delegation deployed to the French capital this week to present the Kingdom’s plan for Riyadh Expo 2030, Prince Faisal said the city could provide a forum that would reflect global diversity and the world’s move towards a sustainable future.

“It is a strategic priority for the Kingdom to deliver an expo built by the world, for the world, an expo which recognizes global diversity, and we seek the opportunity to organize an expo that continues the legacy of international exhibitions at a time when the international community seeks to prepare for a transition to a sustainable and more equal future,” he said.

Saudi Arabia officially submitted its full bid to host the expo last October. Riyadh is up against Busan in South Korea and Rome in Italy. The final selection is due to take place in November.

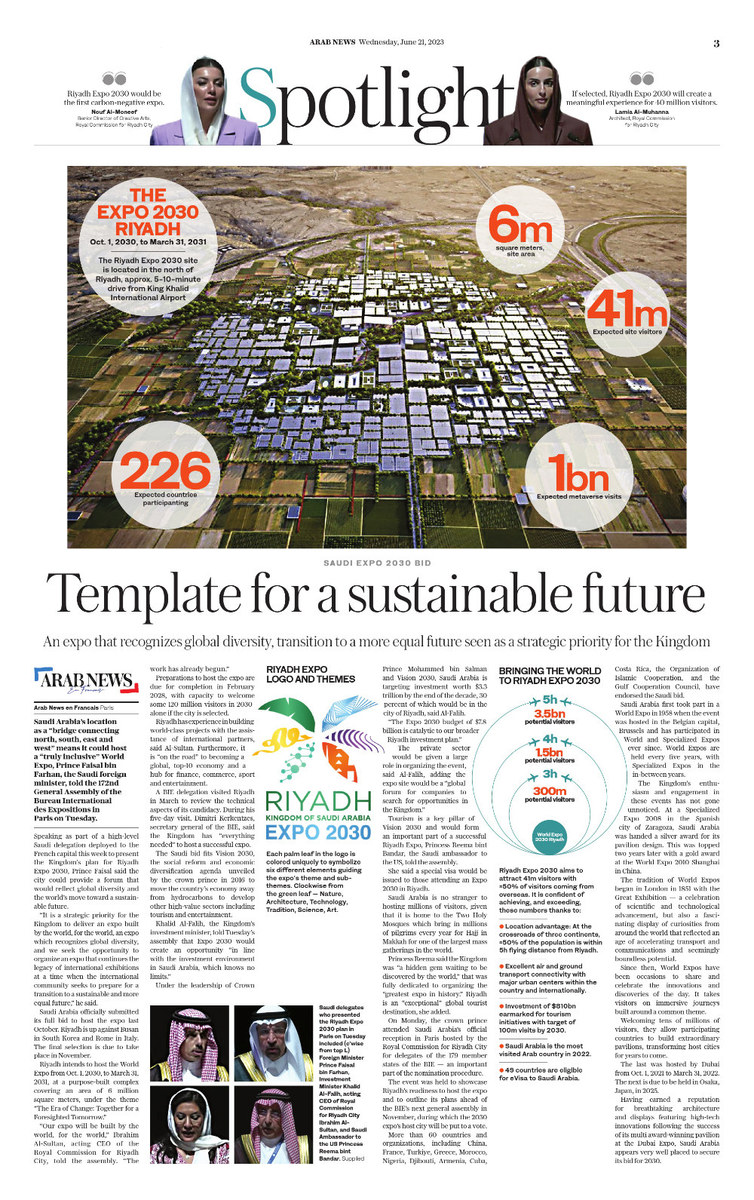

Riyadh intends to host the World Expo from Oct. 1, 2030, to March 31, 2031, at a purpose-built complex covering an area of 6 million square meters, under the theme “The Era of Change: Together for a Foresighted Tomorrow.”

“Our expo will be built by the world, for the world,” Ibrahim Al-Sultan, acting CEO of the Royal Commission for Riyadh City, told the assembly. “The work has already begun.”

Preparations to host the expo are due for completion in February 2028, with capacity to welcome some 120 million visitors in 2030 alone if the city is selected.

Riyadh has experience in building world-class projects with the assistance of international partners, said Al-Sultan. Furthermore, it is “on the road” to becoming a global, top-10 economy and a hub for finance, commerce, sport and entertainment.

A BIE delegation visited Riyadh in March to review the technical aspects of its candidacy. During his five-day visit, Dimitri Kerkentzes, secretary general of the BIE, said the Kingdom has “everything needed” to host a successful expo.

The Saudi bid fits Vision 2030, the social reform and economic diversification agenda unveiled by the crown prince in 2016 to move the country’s economy away from hydrocarbons to develop other high-value sectors including tourism and entertainment.

Khalid Al-Falih, the Kingdom’s investment minister, told Tuesday’s assembly that Expo 2030 would create an opportunity “in line with the investment environment in Saudi Arabia, which knows no limits.”

Lamia Al-Muhanna, on the left, director of landscape architecture, Royal Commission for Riyadh City. (Screenshot/BIE Paris)

Under the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia is targeting investment worth $3.3 trillion by the end of the decade, 30 percent of which would be in the city of Riyadh, said Al-Falih.

“The Expo 2030 budget of $7.8 billion is catalytic to our broader Riyadh investment plan.”

The private sector would be given a large role in organizing the event, said Al-Falih, adding the expo site would be a “global forum for companies to search for opportunities in the Kingdom.”

Tourism is a key pillar of Vision 2030 and would form an important part of a successful Riyadh Expo, Princess Reema bint Bandar, the Saudi ambassador to the US, told the assembly.

She said a special visa would be issued to those attending an Expo 2030 in Riyadh.

Ibrahim Al-Sultan, acting CEO of the Royal Commission for Riyadh City. (Screenshot/BIE Paris)

Saudi Arabia is no stranger to hosting millions of visitors, given that it is home to the Two Holy Mosques which bring in millions of pilgrims every year for Hajj in Makkah for one of the largest mass gatherings in the world.

Princess Reema said the Kingdom was “a hidden gem waiting to be discovered by the world,” that was fully dedicated to organizing the “greatest expo in history.” Riyadh is an “exceptional” global tourist destination, she added.

On Monday, the crown prince attended Saudi Arabia’s official reception in Paris hosted by the Royal Commission for Riyadh City for delegates of the 179 member states of the BIE — an important part of the nomination procedure.

The event was held to showcase Riyadh’s readiness to host the expo and to outline its plans ahead of the BIE’s next general assembly in November, during which the 2030 expo’s host city will be put to a vote.

More than 60 countries and organizations, including China, France, Turkiye, Greece, Morocco, Nigeria, Djibouti, Armenia, Cuba, Costa Rica, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and the Gulf Cooperation Council, have endorsed the Saudi bid.

Saudi Arabia first took part in a World Expo in 1958 when the event was hosted in the Belgian capital, Brussels and has participated in World and Specialized Expos ever since. World Expos are held every five years, with Specialized Expos in the in-between years.

The Kingdom’s enthusiasm and engagement in these events has not gone unnoticed. At a Specialized Expo 2008 in the Spanish city of Zaragoza, Saudi Arabia was handed a silver award for its pavilion design. This was topped two years later with a gold award at the World Expo 2010 Shanghai in China.

The tradition of World Expos began in London in 1851 with the Great Exhibition — a celebration of scientific and technological advancement, but also a fascinating display of curiosities from around the world that reflected an age of accelerating transport and communications and seemingly boundless potential.

Since then, World Expos have been occasions to share and celebrate the innovations and discoveries of the day. It takes visitors on immersive journeys built around a common theme.

Welcoming tens of millions of visitors, they allow participating countries to build extraordinary pavilions, transforming host cities for years to come.

The last was hosted by Dubai from Oct. 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022. The next is due to be held in Osaka, Japan, in 2025.

Having earned a reputation for breathtaking architecture and displays featuring high-tech innovations following the success of its multi award-winning pavilion at the Dubai Expo, Saudi Arabia appears very well placed to secure its bid for 2030.