ISTANBUL: Moscow has welcomed Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's proposal to establish a three-way mechanism for diplomacy between Turkey, Russia and Syria.

Erdogan has brought the new proposal to the table to open a diplomatic channel with Damascus.

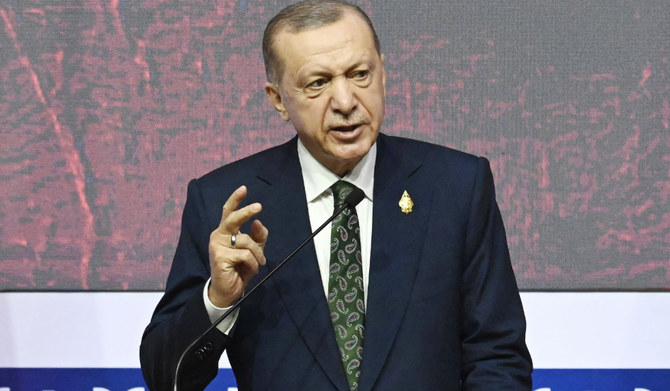

Turkish state-run broadcaster TRT cited Erdogan as telling reporters during his flight back from Turkmenistan that he offered to initiate a series of meetings between Turkiye, Russia and Syria to reconsider strained ties with Damascus.

“As of now, we want to take a step as a Syria-Turkiye-Russia trio. First our intelligence agencies, then defense ministers, and then foreign ministers of the parties could meet. After their meetings, we as the leaders may come together,” Erdogan was quoted as saying.

Erdogan added that he offered this plan to Russian President Vladimir Putin, who viewed it “positively.”

In September, Reuters reported that Hakan Fidan, head of Turkiye’s National Intelligence Organization, had met several times in Damascus with his counterpart, Syrian National Security Bureau Chairman Ali Mamlouk.

Experts noted that the move might be linked with Turkiye’s domestic politics, especially with regard to managing the issue of refugees ahead of the approaching elections, as Erdogan’s main focus has shifted from ousting the Assad regime to curbing advances of Kurdish militants along Turkish borders with Syria.

Erdogan and Syrian President Bashar Assad have not had contact since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, as Ankara supported Syrian opposition forces fighting Damascus.

“For Assad, this is all good news. Normalization with Turkiye would be a major watershed moment in the conflict, even if it won’t suffice to end it or address all the problems faced by his regime,” Aron Lund, fellow with Century International, told Arab News.

If Damascus and Ankara can get back on speaking terms, Lund thinks that they would still have a lot to disagree on — not least Turkiye’s troop presence in Syria.

“But they would also have the opportunity to address common problems, one of which is the role of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces and the US troops in northeastern Syria,” he said.

Lund also emphasized that it is just a proposal and not a done deal.

“It takes two to tango — or three in this case, with Russia. Assad will be able to shape the terms of this process, too, and I’ll be interested to see what the Syrian response will be. The Syrian regime is typically very stubborn about these things, and Assad realizes, of course, that he would be boosting Erdogan’s reelection chances,” he said.

“I don’t think Assad will want to squander the opportunity,” Lund added.

Erdogan “is likely to stay in power one way or the other, and once the elections are over, he may not have the same strong incentive to cozy up to Assad. Still, though, judging by past behavior, I would not be surprised at all if Assad starts to play hardball and stalls the process to extract concessions,” said Lund.

On its side, Russia, Assad’s main backer, has been pushing for reconciliation between Ankara and Damascus for a couple of months.

In September, Mikhail Bogdanov, the Russian president’s deputy foreign minister and special envoy to the Middle East and Africa, said that Moscow is willing to organize a meeting between Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad and Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu.

Following Erdogan’s offer, Bogdanov was quoted by RIA news agency as saying that Moscow reacted positively to the idea of the Turkish president holding a meeting between the leaders of Turkiye, Syria and Russia.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Vershinin was in Turkiye last week to discuss Syria-related developments, while Putin held a phone call with Erdogan on Sunday when the Turkish president asked for a 30-km security corridor on Turkiye’s southern border, in line with the 2019 agreement between Turkiye and Russia.

Under the 2019 deal, Russia guaranteed to establish a buffer zone between the Turkish border and the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, which would be controlled by the Syrian army and Russian military police. The agreement, however, was not fully implemented.

Following a deadly bomb attack in Istanbul that killed six and injured 81, Turkiye carried out an aerial operation against the YPG in northern Syria and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, in northern Iraq on Nov. 20.

Erdogan also pledged a ground operation into northern Syria “at the most convenient time” to build a security strip.

But, Francesco Siccardi, senior program manager and senior research analyst at Carnegie Europe, thinks that for Ankara, normalization with Assad is not an alternative to a ground operation in northern Syria.

“The link between these two policies is Ankara’s interest to undo Kurdish gains in Northern Syria — an objective that it shares with Damascus, too,” he told Arab News.

According to Siccardi, everything Ankara does is calculated to maximize Erdogan’s chances for reelection.

“In this sense, dialogue with Damascus strips the opposition of a key talking point, since they are proposing to do the same,” he said.

“It also allows President Erdogan to present his concrete work toward a solution to the issue of Syrian refugees in Turkiye. And lastly, it puts the security and terrorism issues at the center of the political debate. This approach has benefitted the incumbent president in the past,” Siccardi added.

Turkiye hosts 3.7 million Syrian refugees, the largest refugee population in the world. But the country’s ongoing economic crisis has further fueled anti-Syrian refugee sentiment, pushing several opposition parties to call for forced deportations of Syrians, blaming them for the economic problems of Turkiye.

In the meantime, the trio offer came at a time when Josep Borrell, EU foreign policy chief, criticized Turkiye over its ties with Russia and urged Ankara to join the EU’s sanctions against Moscow.

Prof. Emre Ersen, an expert on Turkiye-Russia relations from Marmara University, thinks that if the two governments finally decide to come together, this could be regarded as a significant achievement for Russian diplomacy, particularly at a time when Moscow is becoming more isolated in the international arena due to the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Yet, Ersen noted a number of thorny issues that need to be resolved between Ankara and Damascus in order for this diplomatic process to be successful.

“Turkiye still continues to support the rebel groups in Syria, which is a major problem for the Assad regime,” he said.

“Damascus is also highly critical of the Turkish military presence in Syria as well as the Turkish army’s cross-border military operations against the Syrian-Kurdish YPG militia. Against this background, the rapprochement process will most likely be quite gradual,” he added.