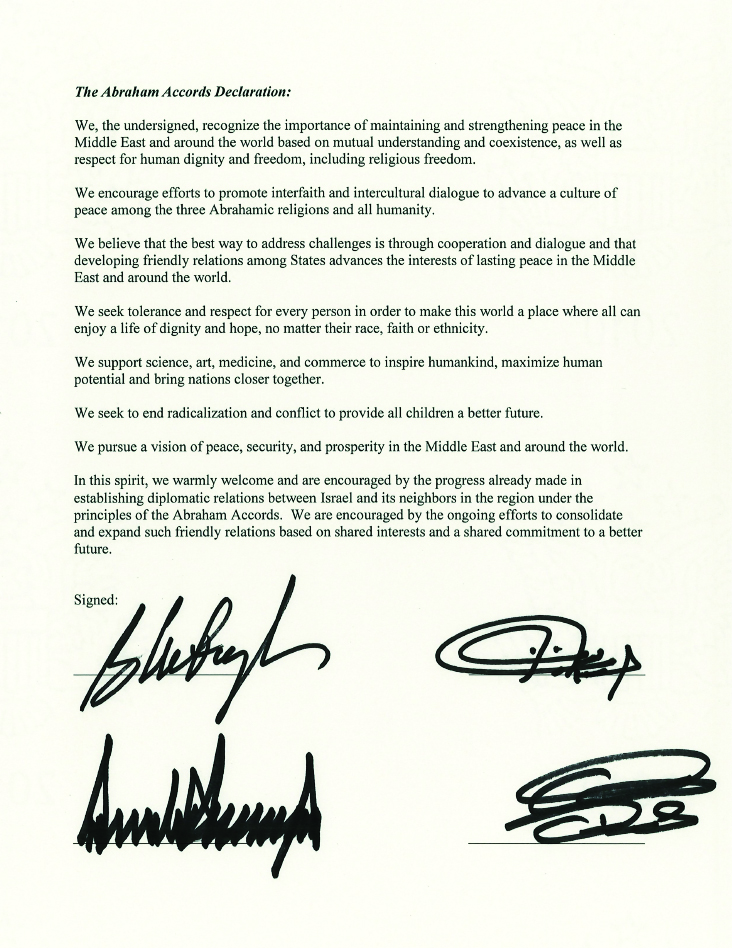

MISSOURI, USA: With the two-year anniversary of the historic Abraham Accords upon us, it seems as good a time as any to reflect upon the changes they heralded for the Middle East and North Africa.

The agreement has normalized relations so far between Israel and four Arab countries: the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan.

Jason Greenblatt’s “In the Path of Abraham” offers readers an inside account of the thinking and process which made the accords possible. Appointed by President Donald Trump in 2016 as representative for international negotiations, Greenblatt, together with Jared Kushner, Ambassador David Friedman and Kushner aide Avi Berkowitz led the US efforts to broker peace between Israel, the Palestinians and their neighbors.

The book offers a very accessible, clear and forthright account of how they approached this monumental task. In the process, Greenblatt and his colleagues had to throw out much of the received wisdom on the Arab-Israeli conflict accumulated over the years and propagated by a vast army of “experts” on the issue.

The long-held consensus view on this conflict maintained that one could not pursue peace and normalization between Israel and various Arab states until after a final peace deal with the Palestinians had been achieved.

That peace deal with the Palestinians proved ever elusive, however, even to this day, effectively giving the Palestinian political parties a veto over anything to do with Israel in the region.

The MENA region has changed over time, however, even if the Israeli-Palestinian conflict appears frozen in place.

The old experts, from academics and think tanks to intelligence officers and people manning desks in the State Department or various foreign ministries, largely failed to appreciate the changes.

Pan-Arabism does not exert the same hold over the Arab world that it once did, and while most Arab leaders and their public remain very sympathetic to the Palestinians, they also have their own state interests to look to.

Iran, in particular, looms very large within the risk assessments of various Arab states, and in Israel they can find a militarily and technologically powerful — and determined foe — of Iran with which to make common cause.

An integral part of the MENA region, whether some like it or not, Israel is also not going anywhere. Indeed, in the present circumstances, Israel will neither lose sight of the threat that Tehran poses, nor fail to grasp the geopolitical significance of a nuclear-armed Iran.

Common interests between many Arab states and Israel go beyond Iran as well, as Greenblatt so astutely understood, and the Palestinian leadership’s intransigence in the face of various Israeli peace offers over the years could no longer be permitted to veto such a confluence of interests.

FASTFACT

2020

The Abraham Accords, signed in September 2020, normalized relations between Israel, the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco.

He writes: “By continuing to make perfect the enemy of the good, the Palestinian Authority had, slowly but surely, eroded much of what was once rock-solid political and financial support by its neighbors.

“For more and more Arab countries, it was one thing to support the desire of Palestinians for a peaceful state, but it had become increasingly untenable to continue to make that cause a higher priority than the competing needs of their citizens who both desired and deserved a more prosperous future as well.”

That common interest resides not just in geopolitical alignments and threats, but in the social and economic realms as well — including energy, food, water, health, and other issues.

Greenblatt provides the example of a recent Rand Corporation study that “forecasts nearly $70 billion in direct new aggregate benefits for Israel and its four partners (the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan) in these free trade agreements over the next decade and the creation of almost 65,000 new jobs.

If all five partners, in turn, trade with one another in a plurilateral FTA, Rand calculates the additional aggregate benefits will exceed $148 billion and the jobs created to exceed 180,000.”

The Arab leaders in the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan proved far-sighted enough and courageous enough to see all this as well and take the necessary steps.

Advocates of the Abraham Accords model argue, rightly or wrongly, that reversing the equation of “peace with the Palestinians first, normalization with the Arab world after” increases the likelihood of arriving at an Israeli-Palestinian peace as well. As evidence, they say some 70 years of Arab League boycotts and shunning of Israel certainly did nothing to achieve peace.

For better or worse, the united Arab front against Israel convinced Israelis of the need to remain militarily strong and vigilant, decreasing their ability to imagine any scenario in which the Arab world would truly accept them and make genuine peace.

Yet since everyone pretty much agrees that an Israeli-Palestinian negotiated peace remains the most difficult and elusive objective, why not marshal the assistance of all those who share that goal?

Most of the Arab states in the MENA region most definitely want a reasonable peaceful settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and now the ones that have normalized relations with Israel can help bring it about.

Jason Greenblatt (L) meeting with Palestinian leader Mahmud Abbas in the West Bank city of Ramallah on May 25, 2017. (AFP file)

They can help broker talks, they can help persuade both Israelis and Palestinians to find a middle ground somewhere, and, most of all, they can become stronger forces for moderate politics in the region.

Greenblatt and his team understood all this. They did not just sense that the Arab region was ready for a change in policy, however.

They tirelessly worked to help bring about the change for the better, and in the process probably improved the lives of millions in the region.

For that we all owe them our thanks.

Unfortunately, the people who could most benefit from reading this account behind the Abraham Accords will probably never do so. People do not, as a rule, like to read about how they were wrong. There are also more minor things in the book to take issue with, which might dissuade some readers.

Many Americans (including this reviewer) will not at all share the author’s extremely high regard for former President Trump, for instance. To such readers, the same president who threw Washington’s Kurdish allies under the bus in 2017 and 2019 — the very allies who defeated Daesh with a US-backed coalition — cannot be trusted to understand the region nor to always make the right call.

Israeli settlers throw stones at Palestinian protesters during a demonstration against settlement expansion in al-Mughayer in the occupied West Bank on July 29, 2022. (AFP file)

I would also expect Israeli policymakers to receive at least some criticism at some point somewhere in the book. The issue of illegal settlements might be a case in point — I still cannot understand how Israel can claim more land in the occupied West Bank (Judea and Samaria) without accepting (meaning offering citizenship to) the people there.

The simple unavoidable calculus supporting a two-state solution still seems to be that you cannot have one without the other — if you take all the land, you need to take all the people there too and offer them equal citizenship. If offering them equal citizenship is too dangerous for Israel, then settlements need to stop in order for the Palestinians to retain enough land for a viable and dignified state of their own — whenever they might be ready for that.

Finally, the issue of the Iran nuclear accords remains a thorny one. The uncomfortable truth is that Iran has made more progress toward building nuclear weapons since Trump pulled the US out of the nuclear accord than in the years following its signing. There may be no good answers here as long as the US lacks the appetite for military conflict with Iran, a lack of appetite that the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations all shared.

(L-R) Bahrain FM Abdullatif al-Zayani, Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu, US President Donald Trump, and UAE FM Abdullah bin Zayed Al-Nahyan during the signing the the Abraham Accords. (AFP)

In Greenblatt’s telling of the issue, things are a good deal simpler: The nuclear deal with Iran was a con job that Obama and Kerry fell for, and Trump put a stop to that. The counterargument is, apart from the targeted assassination of Qassem Soleimani in January 2020, the Trump administration achieved little in the matter of defanging Iran.

The regime remains solidly in place, uranium enrichment has expanded rather than quieted down, and Iranian influence in places such as Iraq and Syria is stronger than ever (especially after Trump chose to let Iranian and Iraqi forces attack Washington’s Kurdish allies in October 2017).

These quibbles notwithstanding, Greenblatt’s book remains well worth picking up. The narrative regarding peace and progress in the MENA region, including an almost contagious optimism for such, could use more space on any bookshelf.

-----------------------

• “In the Path of Abraham,” Jason D. Greenblatt (New York: Wicked Son Publishing, hard cover, 325 pages).

• Reviewer: David Romano, Thomas G. Strong Professor of Middle East Politics, Missouri State University