This year's Nobel Prize season approaches as Russia's invasion of Ukraine has shattered decades of almost uninterrupted peace in Europe and raised the risks of a nuclear disaster.

The secretive Nobel committees never hint who will win the prizes in medicine, physics, chemistry, literature, economics or peace. It's anyone's guess who might win the awards being announced starting Monday.

Yet there's no lack of urgent causes deserving the attention that comes with winning the world's most prestigious prize: Wars in Ukraine and Ethiopia, disruptions to supplies of energy and food, rising inequality, the climate crisis, the ongoing fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The science prizes reward complex achievements beyond the understanding of most. But the recipients of the prizes in peace and literature are often known by a global audience and the choices — or perceived omissions — have sometimes stirred emotional reactions.

Members of the European Parliament have called for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the people of Ukraine to be recognized this year by the Nobel Peace Prize committee for their resistance to the Russian invasion.

While that desire is understandable, that choice is unlikely because the Nobel committee has a history of honoring figures who end conflicts, not wartime leaders, said Dan Smith, director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Smith believes more likely peace prize candidates would be groups or individuals fighting climate change or the International Atomic Energy Agency, a past recipient.

Honoring the IAEA again would recognize its efforts to prevent a radioactive catastrophe at the Russian-occupied Zaporizhzhia atomic power plant at the heart of fighting in Ukraine, and its work in fighting nuclear proliferation, Smith said.

“This is really difficult period in world history and there is not a lot of peace being made,” he said.

Promoting peace isn't always rewarded with a Nobel. India's Mohandas Gandhi, a prominent symbol of non-violence in the 20th century, was never so honored.

But former President Barack Obama was in 2009, sparking criticism from those who said he had not been president long enough to have an impact worthy of the Nobel.

In some cases, the winners have not lived out the values enshrined in the peace prize.

Just this week the Vatican acknowledged imposing disciplinary sanctions on Nobel Peace Prize-winning Bishop Carlos Ximenes Belo following allegations he sexually abused boys in East Timor in the 1990s.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed won in 2019 for making peace with neighboring Eritrea. A year later a largely ethnic conflict erupted in the country's Tigray region. Some accuse Abiy of stoking the tensions, which have resulted in widespread atrocities. Critics have called for his Nobel to be revoked and the Nobel committee has issued a rare admonition to him.

The Myanmar activist Aung San Suu Kyi won the peace prize in 1991 while being under house arrest for her opposition to military rule. Decades later, she was seen as failing in a leadership role to stop atrocities committed by the military against the country's mostly Muslim Rohingya minority.

The Nobel committee has sometimes not awarded a peace prize at all. It paused them during World War I, except to honor the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1917. It didn't hand out any from 1939 to 1943 due to World War II. In 1948, the year Gandhi died, the Norwegian Nobel Committee made no award, citing a lack of a suitable living candidate.

The peace prize also does not always confer protection.

Last year journalists Maria Ressa of the Philippines and Dmitry Muratov of Russia were awarded “for their courageous fight for freedom of expression” in the face of authoritarian governments.

Following the invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin has cracked down even harder on independent media, including Muratov's Novaya Gazeta, Russia’s most renowned independent newspaper. Muratov himself was attacked on a Russian train by an assailant who poured red paint over him, injuring his eyes.

The Philippines government this year ordered the shutdown of Ressa’s news organization, Rappler.

The literature prize, meanwhile, has been notoriously unpredictable.

Few had bet on last year’s winner, Zanzibar-born, U.K.-based writer Abdulrazak Gurnah, whose books explore the personal and societal impacts of colonialism and migration.

Gurnah was only the sixth Nobel literature laureate born in Africa, and the prize has long faced criticism that it is too focused on European and North American writers. It is also male-dominated, with just 16 women among its 118 laureates.

The list of possible winners includes literary giants from around the world: Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, Japan’s Haruki Murakami, Norway’s Jon Fosse, Antigua-born Jamaica Kincaid and France’s Annie Ernaux.

A clear contender is Salman Rushdie, the India-born writer and free-speech advocate who spent years in hiding after Iran’s clerical rulers called for his death over his 1988 novel “The Satanic Verses.” Rushdie, 75, was stabbed and seriously injured at a festival in New York state on Aug. 12.

The prizes to Gurnah in 2021 and U.S. poet Louise Glück in 2020 have helped the literature prize move on from years of controversy and scandal.

In 2018, the award was postponed after sex abuse allegations rocked the Swedish Academy, which names the Nobel literature committee, and sparked an exodus of members. The academy revamped itself but faced more criticism for giving the 2019 literature award to Austria’s Peter Handke, who has been called an apologist for Serbian war crimes.

Some scientists hope the award for physiology or medicine honors colleagues instrumental in the development of the mRNA technology that went into COVID-19 vaccines, which saved millions of lives across the world.

“When we think of Nobel prizes, we think of things that are paradigm shifting, and in a way I see mRNA vaccines and their success with COVID-19 as a turning point for us,” said Deborah Fuller, a microbiology professor at the University of Washington.

The Nobel Prize announcements this year kick off Monday with the prize in physiology or medicine, followed by physics on Tuesday, chemistry on Wednesday and literature Thursday. The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize will be announced on Oct. 7 and the economics award on Oct. 10.

The prizes carry a cash award of 10 million Swedish kronor ($880,000) and will be handed out on Dec. 10.

Nobel Prize season arrives amid war, nuclear fears, hunger

https://arab.news/mhrkr

Nobel Prize season arrives amid war, nuclear fears, hunger

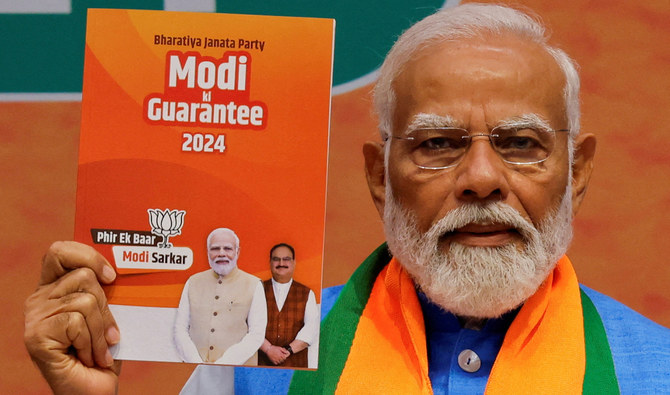

Once a fringe ideology, Hindu nationalism is now mainstream in India

- Modi’s spiritual and political upbringing from the RSS group is the driving force, experts say

- At the same time, his rule has seen brazen attacks against minorities, particularly Muslims

AHMEDABAD: Hindu nationalism, once a fringe ideology in India, is now mainstream. Nobody has done more to advance this cause than Prime Minister Narendra Modi, one of India’s most beloved and polarizing political leaders.

And no entity has had more influence on his political philosophy and ambitions than a paramilitary, right-wing group founded nearly a century ago and known as the RSS.

“We never imagined that we would get power in such a way,” said Ambalal Koshti, 76, who says he first brought Modi into the political wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in the late 1960s in their home state, Gujarat.

Modi was a teenager. Like other young men — and even boys — who joined, he would learn to march in formation, fight, meditate and protect their Hindu homeland.

A few decades earlier, while Mahatma Gandhi preached Hindu-Muslim unity, the RSS advocated for transforming India — by force, if necessary — into a Hindu nation. (A former RSS worker would fire three bullets into Gandhi’s chest in 1948, killing him months after India gained independence.)

Modi’s spiritual and political upbringing from the RSS is the driving force, experts say, in everything he’s done as prime minister over the past 10 years, a period that has seen India become a global power and the world’s fifth-largest economy.

At the same time, his rule has seen brazen attacks against minorities — particularly Muslims — from hate speech to lynchings. India’s democracy, critics say, is faltering as the press, political opponents and courts face growing threats. And Modi has increasingly blurred the line between religion and state.

At 73, Modi is campaigning for a third term in a general election, which starts Friday. He and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party are expected to win. He’s challenged by a broad but divided alliance of regional parties.

Supporters and critics agree on one thing: Modi has achieved staying power by making Hindu nationalism acceptable — desirable, even — to a nation of 1.4 billion that for decades prided itself on pluralism and secularism. With that comes an immense vote bank: 80 percent of Indians are Hindu.

“He is 100 percent an ideological product of the RSS,“in said Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, who wrote a Modi biography. “He has delivered their goals.”

UNITING HINDUS

Between deep breaths under the night sky in western India a few weeks ago, a group of boys recited an RSS prayer in Sanskrit: “All Hindus are the children of Mother India ... we have taken a vow to be equals and a promise to save our religion.”

More than 65 years ago, Modi was one of them. Born in 1950 to a lower-caste family, his first exposure to the RSS was through shakhas — local units — that induct boys by combining religious education with self-defense skills and games.

By the 1970s, Modi was a full-time campaigner, canvassing neighborhoods on bicycle to raise RSS support.

“At that time, Hindus were scared to come together,” Koshti said. “We were trying to unite them.”

The RSS — formed in 1925, with the stated intent to strengthen the Hindu community — was hardly mainstream. It was tainted by links to Gandhi’s assassination and accused of stoking hatred against Muslims as periodic riots roiled India.

For the group, Indian civilization is inseparable from Hinduism, while critics say its philosophy is rooted in Hindu supremacy.

Today, the RSS has spawned a network of affiliated groups, from student and farmer unions to nonprofits and vigilante organizations often accused of violence. Their power — and legitimacy — ultimately comes from the BJP, which emerged from the RSS.

“Until Modi, the BJP had never won a majority on their own in India’s Parliament,” said Christophe Jaffrelot, an expert on Modi and the Hindu right. “For the RSS, it is unprecedented.”

SCALING HIS POLITICS

Modi got his first big political break in 2001, becoming chief minister of home state Gujarat. A few months in, anti-Muslim riots ripped through the region, killing at least 1,000 people.

There were suspicions that Modi quietly supported the riots, but he denied the allegations and India’s top court absolved him over lack of evidence.

Instead of crushing his political career, the riots boosted it.

Modi doubled down on Hindu nationalism, Jaffrelot said, capitalizing on religious tensions for political gain. Gujarat’s reputation suffered from the riots, so he turned to big businesses to build factories, create jobs and spur development.

“This created a political economy — he built close relations with capitalists who in turn backed him,” Jaffrelot said.

Modi became increasingly authoritarian, Jaffrelot described, consolidating power over police and courts and bypassing the media to connect directly with voters.

The “Gujarat Model,” as Modi coined it, portended what he would do as a prime minister.

“He gave Hindu nationalism a populist flavor,” Jaffrelot said. “Modi invented it in Gujarat, and today he has scaled it across the country.”

BIG PLANS

In June, Modi aims not just to win a third time — he’s set a target of receiving two-thirds of the vote. And he’s touted big plans.

“I’m working every moment to make India a developed nation by 2047,” Modi said at a rally. He also wants to abolish poverty and make the economy the world’s third-largest.

If Modi wins, he’ll be the second Indian leader, after Jawaharlal Nehru, to retain power for a third term.

With approval ratings over 70 percent, Modi’s popularity has eclipsed that of his party. Supporters see him as a strongman leader, unafraid to take on India’s enemies, from Pakistan to the liberal elite. He’s backed by the rich, whose wealth has surged under him. For the poor, a slew of free programs, from food to housing, deflect the pain of high unemployment and inflation. Western leaders and companies line up to court him, turning to India as a counterweight against China.

He’s meticulously built his reputation. In a nod to his Hinduism, he practices yoga in front of TV crews and the UN, extols the virtues of a vegetarian diet, and preaches about reclaiming India’s glory. He refers to himself in the third person.

P.K. Laheri, a former senior bureaucrat in Gujarat, said Modi “does not risk anything” when it comes to winning — he goes into the election thinking the party won’t miss a single seat.

The common thread of Modi’s rise, analysts say, is that his most consequential policies are ambitions of the RSS.

In 2019, his government revoked the special status of disputed Kashmir, the country’s only Muslim-majority region. His government passed a citizenship law excluding Muslim migrants. In January, Modi delivered on a longstanding demand from the RSS — and millions of Hindus — when he opened a temple on the site of a razed mosque.

The BJP has denied enacting discriminatory policies and says its work benefits all Indians.

Last week, the BJP said it would pass a common legal code for all Indians — another RSS desire — to replace religious personal laws. Muslim leaders and others oppose it.

But Modi’s politics are appealing to those well beyond right-wing nationalists — the issues have resonated deeply with regular Hindus. Unlike those before him, Modi paints a picture of a rising India as a Hindu one.

Satish Ahlani, a school principal, said he’ll vote for Modi. Today, Ahlani said, Gujarat is thriving — as is India.

“Wherever our name hadn’t reached, it is now there,” he said. “Being Hindu is our identity; that is why we want a Hindu country. ... For the progress of the country, Muslims will have to be with us. They should accept this and come along.”

EU, US reindustrialization accelerates: study

- Report: ‘The rapidity with which reindustrialization has taken hold is remarkable’

- COVID-19 pandemic and Russia's brought to the fore the national security aspect of having control over essential supplies and the necessary manufacturing capacity

PARIS: Companies in Europe and the United States are set to plow more money into bringing manufacturing home after the Covid-19 pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine disrupted the global economy, a study published Thursday found.

The report by consulting firm Capgemini found that companies in 13 industrial sectors in 11 countries in Europe and the United States plan to invest $3.4 trillion over the next three years on bringing manufacturing home or to a nearby country.

That is up from $2.4 trillion in the past three years.

“The rapidity with which reindustrialization has taken hold is remarkable,” said the report.

“Driving this is the imperative to promote supply chain resilience and flexibility; increase both the availability and appeal of skilled manufacturing jobs; meet climate targets; re-establish national security in strategic sectors, and regain the manufacturing might that the industrial powerhouses of Europe and North America once enjoyed,” it added.

The COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted global supply chains, making many companies want to regain greater control over raw materials and components.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine brought to the fore the national security aspect of having control over essential supplies and the necessary manufacturing capacity.

“We were surprised by the magnitude of the phenomenon” of relocalization of manufacturing, one of the report’s authors, Etienne Grass, said.

He noted that the investment represents an average allocation of around 8.7 percent of revenue of the companies it surveyed.

“That’s really a considerable” amount, Grass said.

Some 1,300 senior executives of industrial firms with more than a $1 billion in annual revenue were interviewed for the survey in February.

The companies were located in Britain, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United States.

The top reason cited by companies for reindustrialization was to strengthen their supply chains, followed by the importance of establishing a domestic manufacturing infrastructure to ensure national security.

In third place was reducing greenhouse gas emissions, followed by taking advantage of financial incentives to reindustrialize offered by their governments.

While US companies have the largest reinvestment plans in absolute terms at $1.4 trillion, it trails companies in other nations in terms of percentage of gross domestic product, said Grass.

The German reindustrialization effort is equivalent to 20 percent of GDP and the French effort is 13 percent, compared to five percent for the United States despite the generous subsidies offered under the Inflation Reduction Act.

In addition to bringing production back or near home, companies are also reducing their dependence on China by investing in other emerging market nations, the report found.

“To this end, businesses are distributing their critical assets (such as production facilities, warehouses, and logistics centers) across geographies such as India, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Mexico,” it said.

Ukraine, Israel aid package gains Biden’s support as US House Speaker Johnson fights to keep his job

Ukraine, Israel aid package gains Biden’s support as US House Speaker Johnson fights to keep his job

- Aid package to provide $61 billion for Ukraine, $26 billion for Israel and $8 billion to allies in the Indo-Pacific

- Republican hardliners have moved to oust Johnson, but are expected to fail without support from Democrats

WASHINGTON: President Joe Biden said Wednesday he strongly supports a proposal from Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson to provide aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, sending crucial bipartisan support to the precarious effort to approve $95 billion in funding for the US allies this week.

Before potential weekend voting, Johnson was facing a choice between potentially losing his job and aiding Ukraine. He notified lawmakers earlier Wednesday that he would forge ahead despite growing anger from his right flank. Shortly after Johnson released the aid proposals, the Democratic president offered his emphatic support for the package.

“The House must pass the package this week, and the Senate should quickly follow,” Biden said. “I will sign this into law immediately to send a message to the world: We stand with our friends, and we won’t let Iran or Russia succeed.”

After agonizing for days over how to proceed on the package, Johnson pushed ahead on a plan to hold votes on three funding packages — to provide about $61 billion for Ukraine, $26 billion for Israel and $8 billion to allies in the Indo-Pacific — as well as several other foreign policy proposals in a fourth bill. The plan roughly matches the amounts that the Senate has already approved.

The bulk of the money for Ukraine would go to purchasing weapons and ammunitions from US defense manufacturers. Johnson is also proposing that $9 billion of economic assistance for Kyiv be structured as forgivable loans, along with greater oversight on military aid, but the decision to support Ukraine at all has angered populist conservatives in the House and given new energy to a threat to remove him from the speaker’s office.

Casting himself as a “Reagan Republican,” Johnson told reporters, “Look, history judges us for what we do. This is a critical time right now.”

The votes on the package are expected Saturday evening, Johnson said. But he faces a treacherous path to get there.

The speaker needs Democratic support on the procedural maneuvers to advance his complex plan of holding separate votes on each part of the aid package. Johnson is trying to squeeze the aid through the House’s political divisions on foreign policy by forming unique voting blocs for each issue, then sewing the package back together.

Under the plan, the House would also vote on bill that is a raft of foreign policy proposals. It includes legislation to allow the US to seize frozen Russian central bank assets to rebuild Ukraine; to place sanctions on Iran, Russia, China and criminal organizations that traffic fentanyl; and to potentially ban the video app TikTok if its China-based owner doesn’t sell its stake within a year.

House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries said he planned to gather Democrats for a meeting Thursday morning to discuss the package “as a caucus, as a family, as a team.”

“Our topline commitment is iron-clad,” he told reporters. “We are going to make sure we stand by our democratic allies in Ukraine, in Israel, in the Indo-Pacific and make sure we secure the humanitarian assistance necessary to surge into Gaza and other theaters of war throughout the world.”

The House proposal keeps intact roughly $9 billion in humanitarian aid for civilians in Gaza and other conflict zones. However, progressive Democrats are opposed to providing Israel with money that could be used for its campaign into Gaza that has killed thousands of civilians.

“If they condition the offensive portion of the aid, that would be a conversation, but I can’t vote for more aid to go into Gaza and continue to kill people,” said Rep. Pramila Jayapal, the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus.

Meanwhile, the threat to oust Johnson from Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican of Georgia, gained steam this week. One other Republican, Rep. Thomas Massie of Kentucky, said he was joining Greene and called for Johnson to resign. Other GOP lawmakers have openly defied Johnson’s leadership.

“I want someone that will actually pursue a Republican agenda and knows how to walk in the room and negotiate and not get tossed around the room like some kind of party toy,” Greene said. But she added that she would not move on the motion to vacate Johnson as speaker before the vote on foreign aid.

In an effort to satisfy conservatives, Johnson offered to hold a separate vote on a border security bill, but conservatives rejected that as insufficient. Rep. Chip Roy of Texas called the strategy a “complete failure.”

“We’re going to borrow money that we don’t have — not to defend America, but to defend other nations. We’re going to do nothing to secure our border,” said Rep. Bob Good, the chair of the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus.

With the speaker fighting for his job, his office went into overdrive trumpeting the support rolling in from Republican governors and conservative and religious leaders for keeping Johnson in office.

“Enough is enough,” said Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp on social media. He said “instead of bickering among themselves” the House Republicans should do their “job and vote on the important issues facing our nation.”

At the same time, the speaker’s office was tidying up after Johnson said on Fox News that he and Trump were “100 percent united” on the big agenda items, when in fact the Republican presidential nominee, who had just hosted the House leader in a show of support, opposes much overseas aid as well as a separate national security surveillance bill.

Johnson told CNN on Wednesday that he thought Trump, if elected president, would be “strong enough that he could enter the world stage to broker a peace deal” between Ukraine and Russia.

Yet Johnson’s push to pass the foreign aid comes as alarm grows in Washington at the deteriorating situation in Ukraine. Johnson, delaying an excruciating process, had waited for over two months to bring up the measure since the Senate passed it in February.

“Ukraine is on the verge of collapsing,” said Rep. Michael McCaul, the Republican chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

In a hearing on Wednesday, Pentagon leaders testified that Ukraine and Israel both desperately need military weapons.

“We’re already seeing things on the battlefield begin to shift a bit in Russia’s favor,” said Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin.

The House’s version of the aid bill pushes the Biden administration to provide long-range ATACMS (Army Tactical Missile Systems) to Ukraine, which could be used to target Russian supply lines.

The US has resisted sending those weapons out of concerns Moscow would consider them escalatory, since they could reach deeper into Russia and Russian-held territory. The House legislation would also allow the president to decline to send the ATACMS if it is against national security interests, but Congress would have to be notified.

Still, there was acknowledgement in Washington that Johnson could soon be out as speaker — a job he has held less than five months since Rep. Kevin McCarthy was ousted from the office.

Rep. Don Bacon, a Nebraska Republican, said this week that if Johnson is ousted, he would “be known in history as the man who did the right thing even though it cost him a job.”

Poland’s president becomes the latest leader to visit Donald Trump as allies eye a possible return

- Andrzej Duda, who has long expressed admiration for Trump, is also a staunch supporter of Ukraine in its war against Russia

- He has encouraged the US to provide more aid to Kyiv. That funding has been held up by Trump allies in Congress

NEW YORK: Former President Donald Trump met Wednesday in New York with Polish President Andrzej Duda, the latest in a series of meetings with foreign leaders as Europe braces for the possibility of a second Trump term.

The presumptive Republican nominee hosted Duda for dinner at Trump Tower, where the two were expected to discuss Ukraine, among other topics. Duda, who has long expressed admiration for Trump, is also a staunch supporter of Ukraine and has encouraged Washington to provide more aid to Kyiv amid Russian’s ongoing invasion. That funding has been held up by Trump allies in Congress.

As he arrived, Trump praised the Polish president, saying, “He’s done a fantastic job and he’s my friend.”

“We had four great years together,” Trump added. “We’re behind Poland all the way.”

US allies across the world were caught off guard by Trump’s surprise 2016 win, forcing them to scramble to build relationships with a president who often attacked longstanding treaties and alliances they valued. Setting up meetings with him during the 2024 campaign suggests they don’t want to be behind again.

Even as he goes on trial for one of the four criminal indictments against him, Trump and Democratic President Joe Biden are locked in a rematch that most observers expect will be exceedingly close in November.

“The polls are close,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Connecticut, a Biden ally and a major voice in his party on foreign affairs. “If I were a foreign leader — and there’s a precedent attached to meeting with candidates who are nominated or on the path to being nominated — I’d probably do it too.”

Murphy noted that former President Barack Obama did a lengthy international tour and met with foreign leaders when he first ran for the White House. So did Mitt Romney, the former Massachusetts governor, who challenged Obama in 2012 and whose trip included a stop in Poland’s capital, Warsaw.

Duda’s visit comes a week after Trump met with British Foreign Secretary David Cameron, another NATO member and key proponent of supporting Ukraine, at the former president’s Florida estate.

And last month, Trump hosted Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, an autocrat who has maintained the closest relationship with Russia among European Union countries. Orban shared a montage of footage of the visit on his Instagram feed, with included an image of him and his staff meeting with Trump and the former president’s aides in a scene that looked like an official bilateral meeting.

Trump also met briefly in February with Javier Milei, the fiery, right-wing populist president of Argentina who ran a campaign inspired by Trump, complete with red “Make Argentina Great Again” hats. Milei gave Trump an excited hug backstage at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference outside Washington, according to video posted by a Trump campaign aide.

Biden administration officials have been careful not to weigh in publicly on foreign leaders’ meetings with Trump, who they acknowledge has a real chance of winning the race.

While some officials have privately expressed frustration with such meetings, they are mindful that any criticism would open the US to charges of hypocrisy because senior American officials, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, meet frequently with foreign opposition figures at various forums in the United States and abroad.

Security and policy officials monitor the travel plans of foreign officials visiting the US, but generally don’t have a say in where they go or with whom they meet, according to an administration official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss protocol.

Trump has been back in his hometown this week for the start of his criminal hush money trial, which has dramatically limited his ability to travel and campaign. While in town, aides have been planning a series of events that began Tuesday night when Trump, after court adjourned, stopped by a Harlem bodega where a man was killed to rail against crime and blast the district attorney who made him the first former president in US history to stand criminal trial.

Duda, a right-wing populist who once proposed naming a military base in his country “Fort Trump,” described the dinner earlier Wednesday as a private get-together between friends at Trump’s former residence while he is in town for meetings at the United Nations.

“I have been invited by Mr. Donald Trump to his private apartment,” Duda told reporters, saying it was “a normal practice when one country has good relations with another country” to want those relations to be as strong as “possible with the representatives of various sides of the political stage.”

He described a friendly relationship with Trump built over years of working together.

“We know each other as people. Like two, I can say in some way, friends,” said Duda, whose term ends in 2025.

Duda’s visit comes as House Republicans wrangle over a $95 billion foreign aid bill that would provide new funding to Ukraine, including money for the US military to replace depleting weapon supplies.

Many Trump allies in the House are fiercely opposed to aiding Ukraine, even as the country warns that it is struggling amid a fresh Russian offensive. Trump has said he might be open to aid in the form of a loan.

Like Cameron, Duda’s efforts to push the US to approve additional aid put him in common cause with Biden, who has struggled for six months to unlock additional congressional funding.

One area where Trump and Duda agree when it comes to the conflict are their efforts to push NATO members to increase their defense spending. Duda has called on fellow members of the alliance to raise their spending to 3 percent of gross domestic product as Russia continues its invasion of Ukraine. That would represent a significant increase from the current commitment of 2 percent by 2024.

Trump, in a stunning break from past US precedent, has long been critical of the Western alliance and has threatened not to defend member nations that do not hit that spending goal. That threat strikes at the heart of the alliance’s Article 5, which states that any attack against one NATO member will be considered an attack against all.

In February, Trump went even further, recounting that he’d once told leaders that he would “encourage” Russia to “do whatever the hell they want” to members that are — in his words — “delinquent.”

Duda suggested he intended to raise his proposal at the dinner.

“I have never talked with President Donald Trump about my proposal of raising the spending on defense of NATO countries from 2 percent to 3 percent of GDP, but I think that his approach to it will be positive,” he said.

The visit was met with mixed reaction in Poland, where fears of Russia run high and Duda’s friendly relationship with Trump has been a source of controversy.

Poland’s centrist Prime Minister Donald Tusk, a political opponent of Duda, was critical of the dinner but expressed hope that Duda would use it as an opportunity “to raise the issue of clearly siding with the Western world, democracy and Europe in this Ukrainian-Russian conflict.”

Duda, for his part, said he wasn’t worried since presidents regularly meet with various politicians during foreign trips.

“No, I am not worried because presidents meet with their colleagues, especially with those who had held presidential offices in their respective countries,” he said. “This is regular practice, there is nothing extraordinary here.”

Thousands protest in Georgia as parliament votes on so-called ‘Russian law’ targeting media

- Protesters denounce it as “the Russian law” because Moscow uses similar legislation to stigmatize independent news media

- Opponents say the proposal would obstruct Georgia’s long-sought prospects of joining the European Union

TBILISI, Georgia: Georgia’s parliament has voted in the first reading to approve a proposed law that would require media and non-commercial organizations to register as being under foreign influence if they receive more than 20 percent of their funding from abroad.

Thousands gathered outside parliament to protest. Opponents say the proposal would obstruct Georgia’s long-sought prospects of joining the European Union. They denounce it as “the Russian law” because Moscow uses similar legislation to stigmatize independent news media and organizations seen as being at odds with the Kremlin.

“If it is adopted, it will bring Georgia in line with Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus and those countries where human rights are trampled. It will destroy Georgia’s European path,” said Giorgi Rukhadze, founder of the Georgian Strategic Analysis Center.

In an online statement Wednesday, EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell described the parliament’s move as “a very concerning development” and warned that “the final adoption of this legislation would negatively impact Georgia’s progress on its EU path.”

“This law is not in line with EU core norms and values,” Borrell said.

Borrell said that “Georgia has a vibrant civil society” that is a key part of its EU membership quest.

“The proposed legislation would limit the capacity of civil society and media organizations to operate freely, could limit freedom of expression and unfairly stigmatize organizations that deliver benefits to the citizens of Georgia,” he added.

Although Georgian President Salome Zourabichvili would veto the law if it is passed by parliament in the third reading, the ruling party can override the veto by collecting 76 votes. Then the parliament speaker can sign it into law.

The bill is nearly identical to a proposal that the governing party was pressured to withdraw last year after large street protests. Police in the capital, Tbilisi, used tear gas Tuesday to break up a large demonstration outside the parliament.

Wednesday had an even larger rally. Speaking there, opposition parliament member Aleksandre Ellisashvili denounced lawmakers who voted for the bill as “traitors” and said the rest of Georgia will show them that “people are power, and not the traitor government.”

The only change in wording from the previous draft law says non-commercial organizations and news media that receive 20 percent or more of their funding from overseas would have to register as “pursuing the interests of a foreign power.” The previous draft law said “agents of foreign influence.”

Zaza Bibilashvili with the civil society group Chavchavadze Center called the vote on the law an “existential choice.”

He suggested it would create an Iron Curtain between Georgia and the EU, calling it a way to keep Georgia “in the Russian sphere of influence and away from Europe.”

freedom of expression and unfairly stigmatize organizations that deliver benefits to the citizens of Georgia,” he added.