DUBAI: This summer, at least 20 countries around the world have recorded maximum temperatures of 50 degrees Celsius or above, with extreme heat episodes striking Europe, the Middle East and Africa — often for the first time on record.

The Arab region in particular has experienced progressively extreme temperatures year on year, attributable to long-term variations in weather patterns. Environmental activists warn that at this rate, the reality of climate change could well prove worse than the forecasts.

“Countries in the Middle East that have surpassed temperatures of 50 degrees Celsius include Kuwait, Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE,” Hussein Rifai, chairman of Australian company SPC Global, public speaker and a keen environmentalist, told Arab News.

“Temperatures are expected to rise in the region by at least 4 degrees Celsius by 2050 if greenhouse gases continue to increase at the current rate.”

According to an International Monetary Fund report published in March, temperatures in the Middle East are set to rise by almost half a degree Celsius per decade, leading to extreme weather events including drought, flash flooding and dust storms.

The findings show that climate disasters in the region are already reducing annual economic growth by 1-2 percentage points on a per-capita basis.

“This is not fiction or exaggeration,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said in April, responding to the latest findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“It is what science tells us will result from our current energy policies. We are on a pathway to global warming of more than double the 1.5-degree limit (above pre-industrial levels agreed by world leaders in Paris in 2015).”

The effects can already be seen in Tunisia, where 90 percent of coastal tourism infrastructure is threatened by erosion caused by seawater flooding. Similarly, in Iran a severe drought last year sparked protests as water shortages destroyed farmers’ livelihoods.

Hotter summers and more frequent dust storms have implications for public health, productivity and energy demands say experts. (AFP)

“Climate change is exacerbating desertification and water stress,” said Rifai, whose Shepparton-based company made a commitment last year to a sustainable future for the planet. “Repeated sandstorms like those in Iraq will continue to shut down commerce and send thousands to hospital.”

Because of the Middle East and North Africa’s geographical location, average temperatures have already risen much faster than other inhabited regions, up by around 1.5 degrees Celsius in the last three decades — twice the average global increase of 0.7 degrees.

A study published in the scientific journal Climate Dynamics, which introduces a new and more precise way to project temperatures, claims the threshold for dangerous global warming could be crossed as early as 2027, and certainly by 2042.

“It’s a combination of burning fossil fuels, faulty waste-management systems, continuous deforestation and excessive urbanization, creating greenhouse gases that trap heat in the atmosphere and make the planet warmer,” Zoltan Rendes, chief marketing officer of SunMoney Solar Group, which manages a large community solar-power program, told Arab News.

Erratic weather patterns could be especially harmful for regions that are already hot. Droughts could be longer, deeper and more common, while the frequency of dust storms in the Middle East could double by 2050.

“To put things in perspective, in 2015 a major dust storm blanketed Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq, causing widespread disruption. It was so massive that it could be seen from space,” said Rendes. “One can only imagine how dangerous the situation will be in the years to come.”

Policymakers throughout the Arab world are now grappling with what increasingly hot summers will mean for public health, infrastructure, productivity, the natural environment and energy demand.

No matter what measures are taken at the global and regional levels to slow the pace of global warming, experts say communities will have to adapt quickly to cope with hotter summers and mitigate their most harmful effects.

Research shows that greenhouse-gas emissions are making heatwaves more common and more intense.

Indeed, this summer at least 90 cities worldwide issued heat alerts, urging the public to remain indoors to avoid excessive sun exposure and heat exhaustion.

Iraqi youths beat the heat in the Shatt Al-Arab river in the southern port city of Basra. (AFP)

The elderly, the homeless, and those with pre-existing medical conditions are especially vulnerable. Hundreds of heat-related fatalities were recorded over the summer months in places that lacked the facilities and infrastructure required to deal with the abnormal weather conditions.

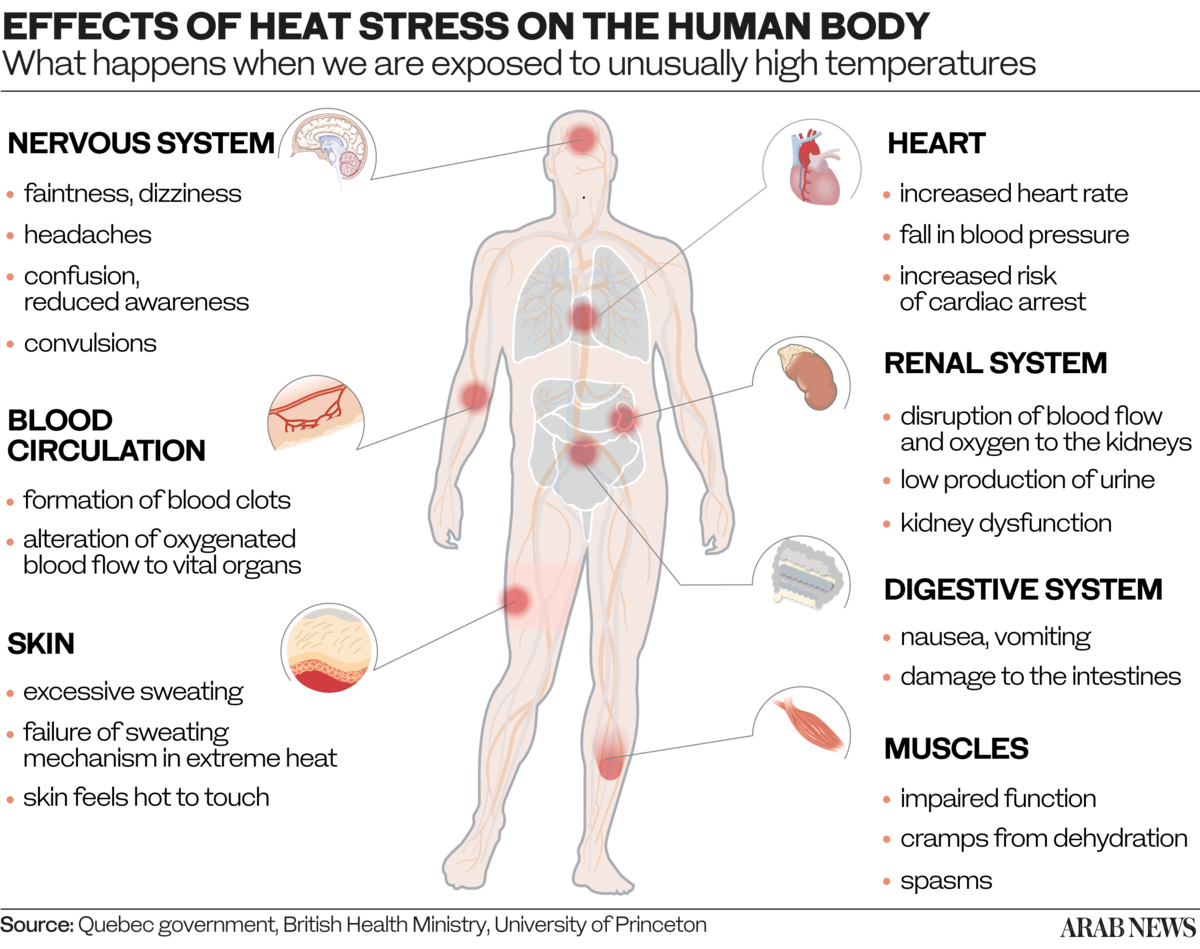

The combination of high temperatures and relative humidity is potentially deadly if the human body is unable to cool off through sweating — a phenomenon known as “wet-bulb” temperatures.

Scientists have calculated that a healthy human adult in the shade with unlimited drinking water will die if wet-bulb temperatures (TW) exceed 35 degrees Celsius for a period of six hours.

It was long assumed this theoretical threshold would never be crossed. However, US researchers came across two locations — one in the UAE, another in Pakistan — where the 35C TW barrier was breached more than once in 2020, if only fleetingly.

Hotter climates will also reduce worker productivity and cause overheated equipment to malfunction.

The Arab world in particular has experienced ever-more extreme temperatures year on year, due to a mixture of suspected man-made climate change and long-term variations in weather patterns. (AFP)

“This is particularly true in manual-labor jobs, but even office workers can be affected when temperatures become too hot,” said Rendes.

Under the circumstances, air conditioners have to work harder to keep people cool, which puts further strain on power grids in the form of higher energy demand.

“If we don’t take action to increase energy efficiency, switch to renewable sources of energy like solar, and propel clean energy solutions through green investments, these problems will grow bigger in the days to come,” said Rendes.

With even roads, railway tracks and runways at risk — some of them literally melted in this year’s summer heat — disruption of economic activity is likely to become more frequent.

Equally worrisome is the increasing risk of conflict and social unrest resulting from human displacement, discomfort and deprivation as rising temperatures destroy livelihoods, overwhelm infrastructure and cause shortages of even basic necessities.

“There will be geopolitical unrest as marginalized citizens fight for access and control of scarce food and water resources,” said Rifai, predicting a looming security threat if no action is taken.

Countries need to be more ambitious with their climate change legislation, the lives and those of future generations are at stake if not, according to Hussein Rifai, SPC Global chairman. (Supplied)

Responding to the challenge, the Gulf states have sought to lower their greenhouse-gas emissions in line with the 2015 Paris Agreement by reducing their reliance on fossil fuels.

The UAE, for instance, has pledged to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, and to invest up to $160 billion in clean and renewable-energy solutions.

Last year, Saudi Arabia launched the Saudi Green and Middle East Green initiatives, committing the Kingdom to reach net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2060 and to plant 10 billion trees over the coming decades.

Rifai thinks widespread adoption of alternative green technologies such as wind turbines, solar panels and battery-powered electric vehicles is the way to go.

If wind and solar-power facilities were to be set up in half the world’s countries, he says, not only would their greenhouse-gas emissions be negligible, but the combined cost of installing them would be much lower than operating the existing fossil-fuel power plants.

Some Gulf countries have made notable progress in the development of utility-scale solar and wind power, including the third phase of the Mohammed bin Rashid solar project in Dubai completed last year, and the inauguration of Saudi Arabia’s first wind farm at Dumat Al-Jandal.

A man rides his scooter along a street during a sand storm in Dubai, on August 14, 2022. (AFP)

Saudi authorities aim to increase the Kingdom’s solar-photovoltaic power-generation capacity to 40 gigawatts by 2030.

Another sustainable-energy source being explored by Gulf states is hydrogen, which is regarded by many experts as a clean fuel of the future, particularly green hydrogen, which is produced using solar energy.

Some countries are also tapping the potential of artificial rain to combat drought and increasing aridity.

Cloud seeding is a man-made intervention to increase precipitation, where clouds are seeded by aircraft or ground rockets, which then release the required material, most commonly silver iodide.

Worldwide, as many as 56 countries are using cloud-seeding technology, according to the World Meteorological Organization. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have both launched programs to boost precipitation.

“In the UAE, where warm clouds are prevalent, salts mixed with magnesium, sodium chloride and potassium chloride are used,” Rifai said.

Palestinian children play in a public fountain during a hot summer day in Gaza City. (AFP)

Of late, the UAE has been testing a new method of cloud seeding by using drones that zap clouds with electricity. Rifai believes more research is needed to fine-tune cloud-seeding technologies.

“It’s not a perfect solution to drought issues, as it requires the presence of clouds to work and a specific type of cumulus cloud. In drought-affected areas, there are likely to be fewer seedable clouds,” he said.

Viewed together, the aforesaid clean-energy, environmental and weather-modification initiatives show that Arab countries that have the requisite resources and political will are getting to grips with the climate crisis.

Even so, hotter temperatures appear to be the new normal, which Middle East populations will simply have to adapt to.

“It’s not too late, but countries need to be more ambitious with their climate-change legislation. Our lives and those of our future generations are truly at stake,” Rifai said.

“Rich nations that have pledged billions in annual funding to help poor countries transition to renewable energy have to start delivering on this promise.”