COLOMBO, Sri Lanka: Don’t fall ill or get into accidents: That’s the advice doctors in Sri Lanka are giving patients as the country’s economic crisis leaves its health care system short of drugs and other vital supplies.

The South Asian island nation lacks the money to pay for basic imports like fuel and food, and medicine is also running out. Such troubles threaten to undo its huge gains in public health in recent decades.

Some doctors have turned to social media to try to get donations of supplies or the funds to buy them. They’re also urging Sri Lankans living overseas to help out. So far there’s no sign of an end to the crisis that has thrust the country into an economic and political meltdown.

Jesmi Fatima shows a prescription given by doctors to undergo pathology tests that were already delayed due to lack of supplies in Colombo, Sri Lanka, June 3, 2022. (AP)

That means 15-year-old Hasini Wasana might not get the medicine she needs to protect her transplanted kidney. Diagnosed with a kidney ailment as a toddler, she got a transplant nine months ago and needs to take an immune suppressant every day for the rest of her life to prevent her body from rejecting the organ.

Hasini’s family is depending on donors to help now that her hospital can no longer provide the Tacrolimus tablets that she received for free until a few weeks ago. She takes eight and a half tablets a day and the cost adds up to more than $200 a month, just for that one medicine.

“We are being told (by the hospital) that they don’t know when they will have this tablet again,” said Ishara Thilini, Hasini’s older sister.

The family sold their home and Hasini’s father got a job in the Middle East to help pay for her medical treatment, but his income is barely enough.

Cancer hospitals, too, are struggling to maintain stocks of essential drugs to ensure uninterrupted treatment.

“Don’t get ill, don’t get injured, don’t do anything that will make you go to a hospital for treatment unnecessarily,” said Samath Dharmaratne, president of the Sri Lanka Medical Association.

“That is how I can explain it; this is a serious situation.”

Dr. Charles Nugawela, who heads a kidney hospital in Sri Lanka’s capital, Colombo, said his hospital has kept running thanks to the largesse of donors but has resorted to providing medicine only to patients whose illness has advanced to the stage where they need dialysis.

Nugawela worries the hospital might have to put off all but the most urgent surgeries because of a shortage of suture materials.

Mohammed Feroze, a kidney patient, puts on his shirt as he waits to buy medicine in Colombo, Sri Lanka, June 3, 2022. (AP)

The Sri Lanka College of Oncologists gave a list of drugs to the Health Ministry that “are very essential, that all hospitals have to have all the time so that we could provide cancer treatment without any interruption,” said Dr. Nadarajah Jeyakumaran, who heads the college.

But the government is having a hard time providing them, he said.

And it’s not just medicine. Patients having chemotherapy are susceptible to infections and can’t eat normally but hospitals don’t have enough food supplements, Jeyakumaran said.

The situation threatens to bring on a health emergency at a time when the country is still recovering from the coronavirus pandemic.

Hospitals lack drugs for rabies, epilepsy and sexually transmitted diseases. Labs don’t have enough of the reagents needed to run full blood count tests. Items like suture material, cotton socks for surgery, supplies for blood transfusions, even cotton wool and gauze are running short.

“If you are handling animals, be careful. If you get bitten and you need surgery and you get rabies, we don’t have adequate antiserum and rabies vaccines,” said Dr. Surantha Perera, vice president of the Sri Lanka Medical Association.

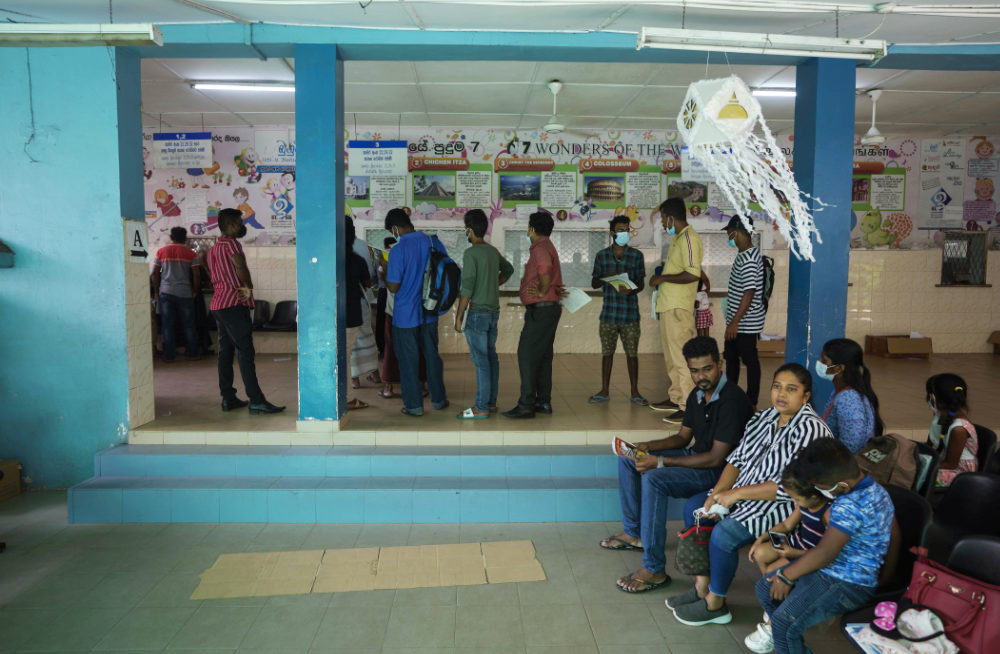

People wait to receive medicine at a pharmacy in a government hospital for children in Colombo, Sri Lanka, June 6, 2022. (AP)

The association is trying to help patients by seeking donations through personal contacts and from Sri Lankans living overseas, Perera said.

Dhamaratne, the association president, said if things don’t improve doctors may be forced to choose which patients get treatment.

It’s a reversal of decades of improvements thanks to a universal health care system that has raised many measures of health to the levels of much wealthier nations.

Sri Lanka’s infant mortality rate, at just under 7 per 1,000 live births, is not far from the US, with 5 per 1,000 live births, or Japan’s 1.6. Its maternal mortality rate of near 30 per 100,000 compares well with most developing countries. The US rate is 19, while Japan’s is 5.

Life expectancy had risen to nearly 75 years by 2016 from under 72 years in 2000.

The country has managed to eliminate malaria, polio, leprosy, the tropical parasitic disease filariasis commonly known as elephantiasis, and most other vaccine-preventable diseases.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has appealed for help, and the US, Japan, India and other countries have pledged funds and other humanitarian support. That aid and more from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and other agencies will ensure medical supplies until the end of next year, Wickremesinghe recently told lawmakers.

But in the hospital wards and operating rooms, the situation seems much less reassuring and it threatens to erode public trust in the health system, Dhamaratne said.

“Compared to COVID, as a health emergency today’s situation is far, far worse,” he said.