NEW YORK CITY: As the breadbasket of the world remains engulfed in conflict, households in vulnerable and poor countries, as well as refugee camps around the world, are getting burned.

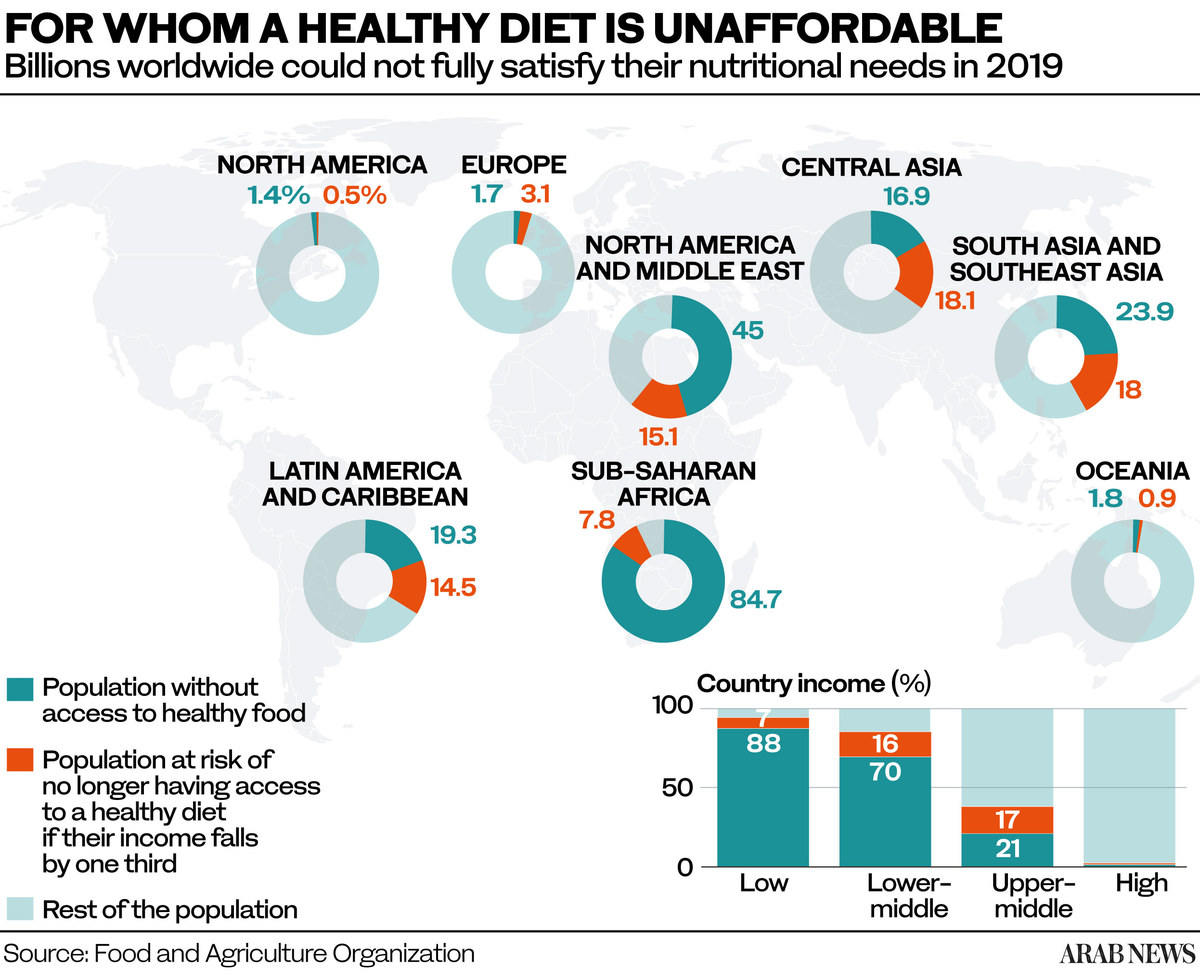

The Russia-Ukraine conflict is threatening to cause a global food crisis that could drive up hunger and undernourishment levels in the Middle East, Central Asia and beyond. The three Fs — food, fuel and fertilizers — could become rare commodities enjoyed by the few if the fighting in Ukraine continues.

The war erupted after two painful years of a pandemic that destroyed livelihoods around the world, strained financial resources and emptied wallets, especially in poor countries.

Fiscal difficulties and inflation were joined by extreme weather in the form of floods and droughts that added to the already considerable stress on the world economy, hampering recovery.

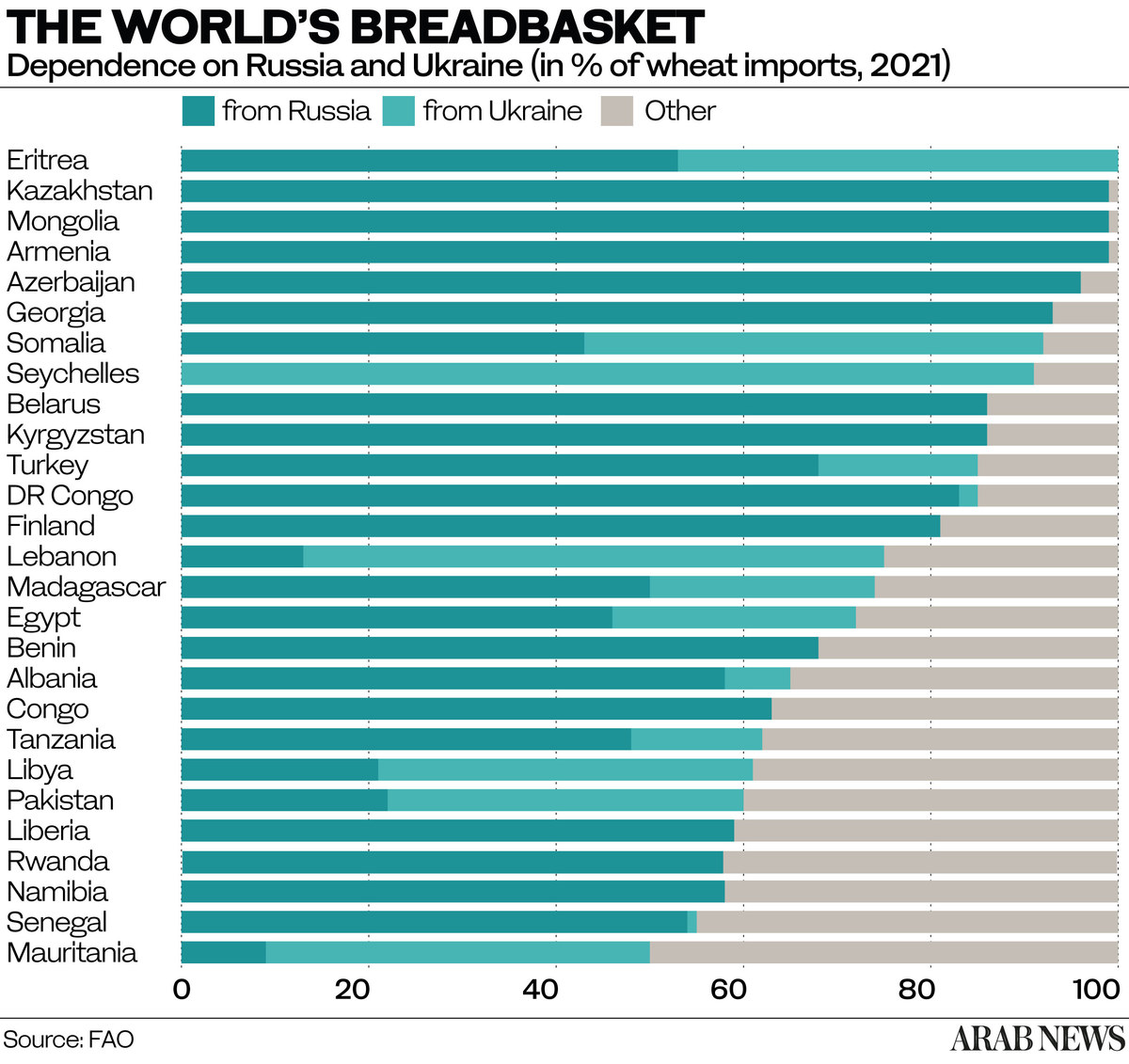

The war in Ukraine created a perfect storm because the two countries involved in it controlled 30 percent of wheat exports of the global market in 2021, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

Russia, the largest exporter of wheat in the world, and Ukraine, the fifth largest, have between them 50 countries around the world that depend on them for 30 percent, some up to 60 percent, of wheat imports. Russia and Ukraine also account for 75 percent of global sunflower seed oil production.

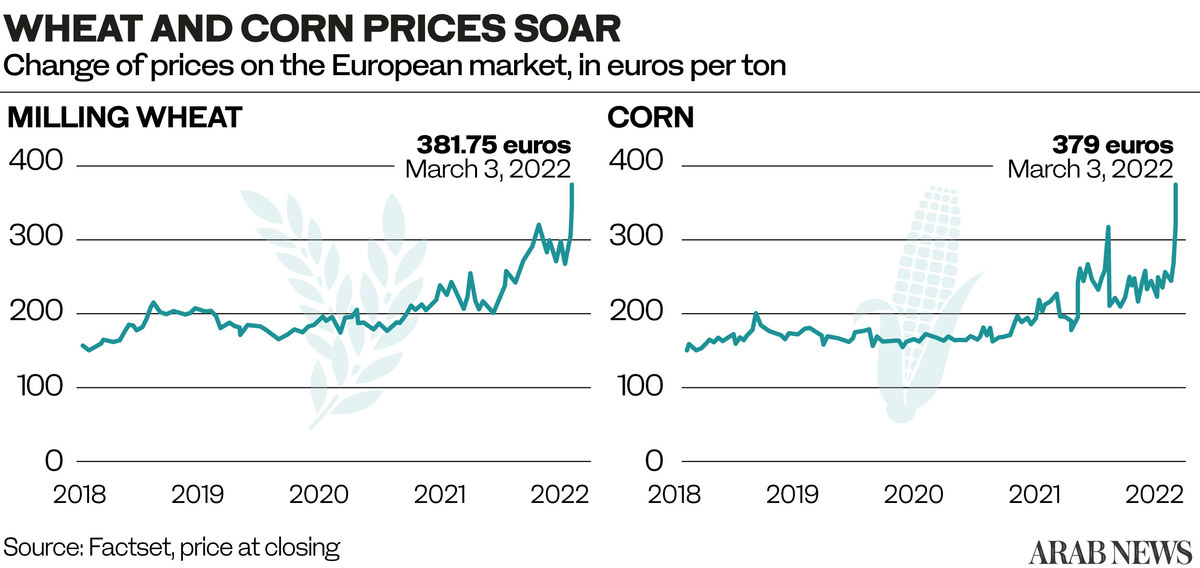

Wheat prices rose 55 percent a week before the war started, coming on the heels of a year that saw wheat prices surge 69 percent. It was also at a time when hunger was on the rise in many parts of the world, especially in the Asia Pacific region, according to the FAO. The pandemic led to an 18 percent rise in hunger, bringing the number of malnourished people to 811 million around the world.

Arab countries, notably Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Libya and Tunisia, rely heavily on Black Sea grain imported from Russia and Ukraine. They buy more than 60 percent of their wheat from the two countries.

A Russian man shovels grain at a farm in Vasyurinskoe. (AFP/File Photo)

These countries, themselves beset by economic problems or conflict, are now facing a difficult situation. In Lebanon for example, half of wheat in 2020 came from Ukraine. The corresponding figures for Libya, Yemen and Egypt were 43 percent, 22 percent and 14 percent, respectively.

The Arab Gulf region, according to IMF officials, will be less affected than other countries in the region because of the fiscal cushion provided by the windfall from high oil prices.

Countries are looking for solutions. But even if importers seek to replace Russia and Ukraine, they will face multiple challenges in looking for an alternative source of wheat supply.

The rise in energy prices is adding to the problem and leading to drastic increases in the price of food and wheat products. The new high price of oil is making importing wheat from distant producers, either in North and South America like the US, Canada and Argentina, or in Australia, very costly. Shipping costs have also increased along with insurance fees because of the conflict, adding to the ballooning price of wheat and food products.

Many wheat producers have resorted to protective policies and restrictions on wheat exports, to ensure enough domestic reserves for their populations. The immorality of vaccine inequality could pale in comparison to that of wheat hoarding by countries that have the financial means to do so. Competition will be fierce and poor countries will be pushed out of the market, causing shortages and tragedies.

One UN agency that feeds the poor and hungry is already feeling the financial pinch. The World Food Program buys almost half of its global wheat supply from Ukraine and the surge in price is affecting its ability to feed the hungry around the world.

According to one WFP official, its expenditure has “already increased by $71 million a month, enough to cut the daily rations for 3.8 million people.”

David Beasley, head of the World Food Program, was quoted as saying “we will be taking food from the hungry to give to the starving.”

A Syrian man, wearing a protective face mask to protect against the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, waits for customers at his bakery. (AFP/File Photo)

Climate change and extreme weather are compounding the problem, with floods and droughts in places such China and Brazil leading to shrinking crops and creating a need to import wheat from outside to satisfy domestic demand. This will ramp up the pressure on global supply and lead to a wheat rush.

The other factor fueling the crisis is a surge in the price of fertilizers. Russia is the world’s largest fertilizer exporter, with 15 percent of the world’s supply. Reports suggest it has asked its producers to halt fertilizer exports.

The sanctions slapped by the West on Russian entities are making payments difficult for exporters and importers alike, leading to a freeze in the fertilizer market. With less fertilizer available because of shortages and high prices, there will be less crop yield and more demand, potentially pushing up food prices further.

Importers of Russian wheat and fertilizers are frustrated and concerned about their ability to meet their needs, and have begun assigning blame.

Noorudin Zafer Ahmadi, An Afghan merchant who imports cooking oil from Russia to Afghanistan, told The New York Times that he found it difficult to buy what he needs in Russia and complained about the surge in prices. But he did not blame Russia; rather, he pointed the finger at those imposing the sanctions. “The US thinks it has only sanctioned Russia and its banks. But the US has sanctioned the whole world,” he told the newspaper.

In the worst-case scenario, food shortages can trigger protests and instability in already volatile countries, or those that are facing financial difficulties.

Surging food prices, especially those of bread, are historically associated with riots and unrest in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa, especially poorer ones. Asked about the potential regional impact of the deteriorating situation, Dr. Jihad Azour, director of the Middle East and Central Asia Department at the IMF, said: “Rising food and energy prices would further fuel inflation and social tensions in both regions (the Middle East and North Africa).

“The increase of food prices will have an impact on overall inflation and put additional pressure on low-income groups, particularly in the least developed countries with a high share of food in their consumption basket, and may trigger a rise in subsidies to counter these pressures, worsening fiscal accounts further,” he told Arab News.

David Beasley, head of the World Food Program. (Supplied)

Discussing the measures that the IMF is taking to help soften the blow to affected countries, Azour said: “The crisis adds to the policy trade-offs which have already become increasingly complex for many countries in the region with rising inflation, limited fiscal space and a fragile recovery.

“The IMF stands ready to help the MENA countries and others as was done during the COVID-19 crisis, where the IMF provided more than $20 billion in financial assistance to several MENA countries, in addition to about $45 billion of special drawing rights distributed last year that constitute an important liquidity line to deal with the various shocks.”

Antonio Guterres, the UN secretary-general, has announced new plans and measures for the organization to help mitigate the situation in countries most affected by soaring grain prices owing to the Ukraine war. He has said he is in touch with the heads of the IMF and the World Bank to coordinate their efforts in handling the crisis.

However, with Russian and Ukrainian forces seemingly locked in a standoff and the conflict showing no sign of ending, the food crisis could be just the beginning.

There are attempts being made by international organizations, at an inter-governmental level, to mitigate the impact of the food crisis on the most vulnerable countries. If these efforts fail to bear fruit, the coming months and years will see hunger on every door.