RIYADH: Unlike other companies that displayed the latest technology at Riyadh’s recent Made in Saudi exhibition, the Aloqailat Museum showed visitors the history and origins of the country’s industry.

The museum, which was established 22 years ago in Qassim, took visitors on a journey to the past about Saudi culture and how trading used to be done.

“Aloqailat (trading) is a commercial profession that does not belong to a tribe or a family,” Abdulatif Alwehibi, the museum's owner and author of the Aloqailat Encyclopedia, told Arab News.

“They are traders who export camels and horses from Najd to all markets within Arab countries. They go to trade and come back with things they do not have in their countries. They also export valuable spices and deliver sheep, ghee, and weapons. Because of this, their reputation spread widely, and they made a name for themselves.”

This display of two men in the desert surrounded by camels tells the story of the lack of security in the past, as there were many thieves. (AN photo by Rahaf Jambi)

The museum showcases the tools and other items that were important for their business such as guns, saddles, big pouches, ropes, everything related to camel care and trade, and also how they used to protect themselves when it came to travel.

At the expo, the museum had three life-sized camels in a desert setting and two characters telling the story of traders.

“This display of two men in the desert surrounded by camels tells the story of the lack of security in the past as there were many thieves and many looting operations. In the display, you find that there are men hiding behind the camel to protect themselves from thieves. The camels’ heads act as a radar, so if they see any stranger, their behavior changes immediately as a warning to their owners.”

HIGHLIGHT

The Made in Saudi expo showcased the products of more than 150 local companies and manufacturers with workshops, lectures covering a range of subjects, and thousands of local products.

During the pilgrimage season, the Aloqailats, who participated in business and trade matters, supplied a number of horses and 500 camels for pilgrims to Madinah and Makkah after an official command from King Abdulaziz.

Zakaria Alwehibi, deputy supervisor of the museum, said the king loved the Aloqailats and gathered them close to him.

A 150 years old Camel's saddle in Aloqilat mobile museum in Saudi Made exhibition. (AN photo by Rahaf Jambi)

“As an appreciation gesture from King Abdulaziz, he assigned Aloqailats in high positions. They founded Riyadh Police, established the armed forces, and were the first ambassadors and ministers during the reign of King Abdulaziz.”

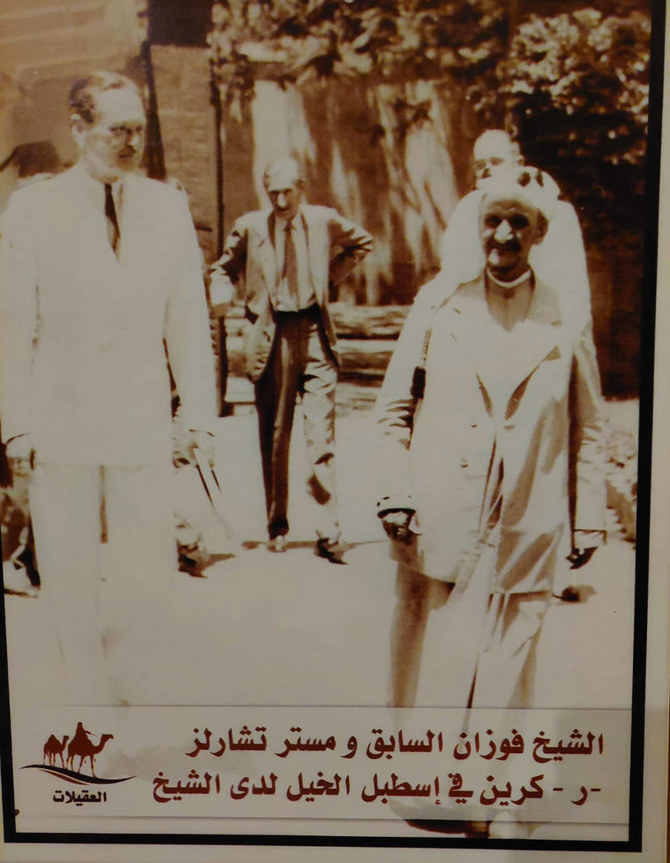

He talked about a trader called Sheikh Al-Fawzan, who is considered to be the reason for the discovery of petroleum in the Arabian Peninsula.

The story dates back to 1927, when he was Saudi Arabia’s first ambassador to Egypt. He was known for his love and passion for breeding purebred Arabian horses and he was the most famous horse breeder in Egypt.

“Charles Crane, an American businessman who was a fan of Arabian horses, was hosted by Sheikh Al-Fawzan in Egypt at his stable. Crane asked about Fawzan’s horses and was then gifted a horse by him as a form of generosity.

Aloqilat's rifles that date back to 100 years in Aloqilat mobile museum. (AN photo by Rahaf Jambi)

“Crane sent a message to Al-Fawzan with his desire to explore oil in the Kingdom. Then he received an invitation from the minister of industry. I think our contribution to the exhibition is important because the history of Aloqailat is important to exist as people love its history.”

The museum’s display at the Made in Saudi event included more than 50 paintings highlighting the role of Aloqailats in the Kingdom’s commercial industries, manuscripts dating back more than a century, and more than 50 local and international participants to show off the centuries-long history of Aloqailats.

Abdulatif invited people to visit the original museum in Qassim, saying it had a rich history that all citizens should know about.

The Qassim museum, which has more than 3,500 photos, aims to preserve the industrial and commercial heritage of the Kingdom and to fuse history, heritage, and culture.

The Made in Saudi expo showcased thousands of products from more than 150 local companies and manufacturers. There were also workshops and lectures covering a range of subjects.