CAIRO: The ancient Egyptians saw death as a temporary interruption rather than the cessation of life. Death was simply part of the journey, toward an individual’s immortality and experience of the afterlife. The pyramids of Giza are not only breathtaking for their monumental stature — to this day a feat of human ingenuity — but also awe-inspiring because of their spiritual significance and their resistance against time.

Giza’s pyramids were given new life earlier this week when the multidisciplinary arts entity Art D’Egypte opened “Forever is Now” on Oct. 21. The title of the exhibition, which will run until Nov. 7, is apt considering the pyramids’ history and, now, their new role in the first-ever contemporary art exhibition staged amidst their stately presence in 4,500 years. The exhibition, curated by independent arts advisor Simon Watson, features works by 10 contemporary artists, including Sultan bin Fahad, Alexander Ponomarev, Gisela Colon, Joao Trevisan, Lorenzo Quinn, JR, Moataz Nasr, Sherin Guirguis, Shuster + Moseley and Stephen Cox.

“Eternity Now” by Gisela Colon. Supplied/Hesham Al-Saifi

Held under the auspices of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and Tourism, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the patronage of UNESCO, the exhibition is the fourth staged by Art D’Egypte since its establishment in 2016. These have included shows of contemporary Egyptian and international art at the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, Manial Palace Museum and on Al-Muizz Street in historic Cairo.

American artist Colon’s “Eternity Now” (2021) demonstrates how the art of today can dialogue with the UNESCO heritage site. It features a 30-foot-long golden elliptical dome that could pass for something from outer space. The dome’s formal geometric aspects embody the mythical shape of the Egyptian sun god Ra’s glowing orb, “the venerable chroma of gold being omnipresent in Egyptian symbolism and ritualism,” as Colon explains. Visitors can catch a magical glimpse of their own reflection and that of their surroundings, which include Giza and its pyramids, by looking into its glossy exterior. The artwork thus allows the spectator, the artwork, and the ancient pyramids to become one for a brief second.

“The exhibition was historic, in the sense that it placed contemporary artworks within the backdrop of ancient history,” Colon told Arab News.

“Greetings From Giza” by JR. Supplied/Ammar Abd Rabbo

Staging 10 contemporary art installations by Middle Eastern and international artists was no easy feat, but Nadine Abdel Ghaffar, founder and director of Art D’Egypte, did not give up.

“I think if I knew how difficult it would be to stage this show, I might have shied away from it,” Abdel Ghaffar told Arab News. “Our archaeologists are not usually taken by the idea of contemporary art, so it took a lot of time to convince them to stage this show at the pyramids. Placing art here made a statement to the world, as the pyramids are not only Egyptian heritage but world heritage. The pyramids are one of the only ancient wonders still standing. Until now, there has never been a contemporary art exhibition at the pyramids of Giza.”

A powerful curatorial tactic involved placing each work within the perspective of the pyramids themselves so that their silhouettes and inherent features played with the forms of the ancient structures.

Egyptian LA-based artist Guirguis’ work, “Here I Have Returned” (2021) — a title inspired by a poem from the great Doria Shafik — features an elegant abstracted curved form with two steel disks dangling from two ropes that chime in a window. Guirguis’ installation perfectly frames the three Giza pyramids as if it were made for this very location. It is also scented with jasmine harvested by Egyptian women. According to Guirguis, the piece is meant to honor Egyptian women of the ancient past and those of the 1950s who fought for their freedom.

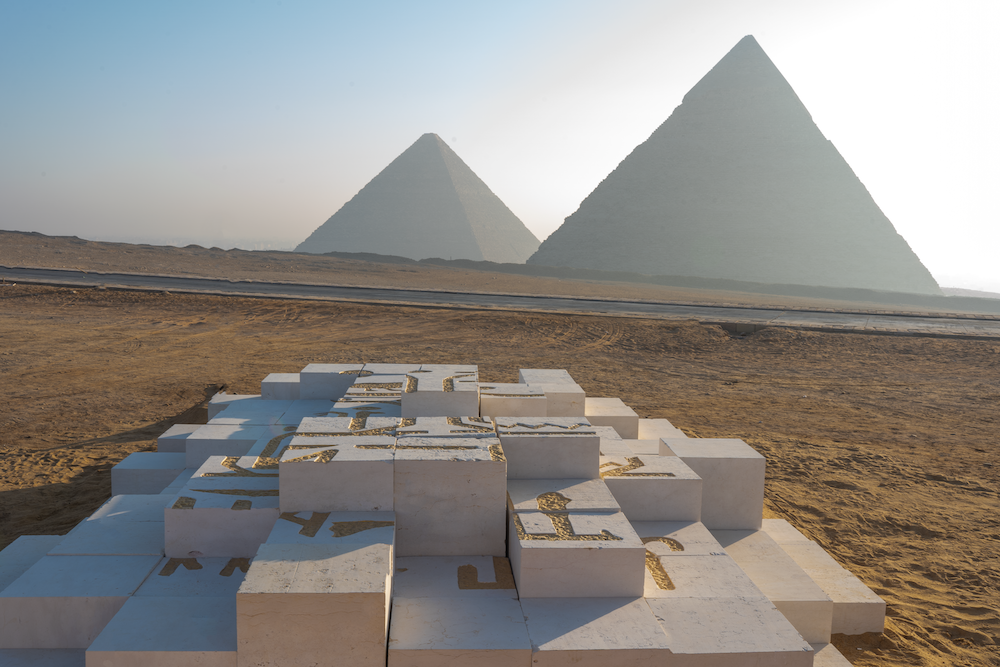

“R III” (2021), Sultan bin Fahad. Supplied/Hesham Al-Saifi

In Saudi artist Fahad’s “R III” (2021), a maze of stacked white cubes presents hieroglyphic inscriptions belonging to King Ramses III. The inscriptions were discovered by Saudi archaeologists in the northern part of the Kingdom. Fahad’s cubes, framed by the powerful forms of the nearby pyramids, shimmer when seen under the moonlight. The work investigates the historic roots between Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

Egyptian artist Nasr’s powerful piece “Barzakh” (2021) presents a series of oars joined together to form a triangular corridor. Inspired by the solar boat of the Egyptians, made to carry the souls of the pharaohs to the heavens, the work allows spectators to get a glimpse of the pyramids in the distance — perfectly framed by the triangular shape created in Nasr’s installation.

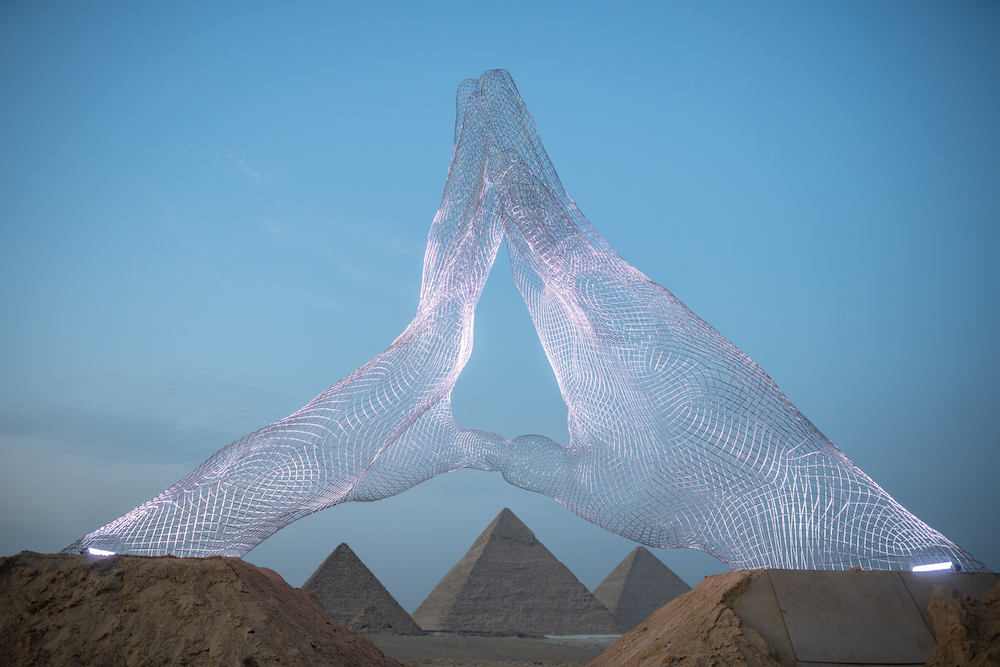

One of the most popular and perhaps moving installations is artist Quinn’s “Together” (2021), which shows two hands joined together in what appears to be a prayer. It is positioned so that the tips of the pyramids can be seen from just inside the hands.

“I will cherish forever this emotional moment in life,” Quinn told Arab News. “Exhibiting my art in front of one of the only standing wonders of the ancient world is beyond anything I had ever hoped for. My work, ‘Together,’ was made in honor of the pyramids and of Ra, the ancient Egyptian god of the sun, as well as the work of my father.” Quinn is the fifth son of actor Anthony Quinn.

‘Together,’ Lorenzo Quinn. Supplied/Hesham Al-Saifi

As for the fate of the artworks in the exhibition, Art d’Egypte’s plan is to have them remain in Egypt after the show concludes. In this sense, “Forever is Now” continues, like its name and the legacy of the pyramids, to live on both metaphorically and physically, carrying with it the memory of a short-lived contemporary art exhibition at the pyramids that surely will stand the test of time.

Not everyone in Egypt, however, was in favor of this exhibition. Most recently, Instagram account @Fartdegypte, with the line “Leave the pyramids alone” in its bio, quickly gathered 1,106 followers and has posted harsh criticism of the event, condemning it as an “Instagrammable Burning Man” show that makes a mockery of the ancient structures and offers access only to the few elite — many of whom have traveled to see the show from the farthest corners of the world.

Moataz Nasr, “Barzakh” (2021). Supplied/Hesham Al-Saifi

“Imagine a future where Pharrell, in Egypt, is surrounded by privileged Egyptians and white people all wearing symbols of the Ottoman Empire,” stated the most recent post. “A future where clout and culture are practically the same? You don’t have to wait too long my friends. This is happening. Right now. The future is now.”

Regardless of the criticism, the fact remains that staging contemporary artworks by such a riveting list of artists at the Giza Pyramids is no easy feat. Importantly, it is turned the world’s eyes once again to the wonders of Egypt, reminding people of the enduring beauty, knowledge and power still be to gained from dialogue with humanity’s ancient past.