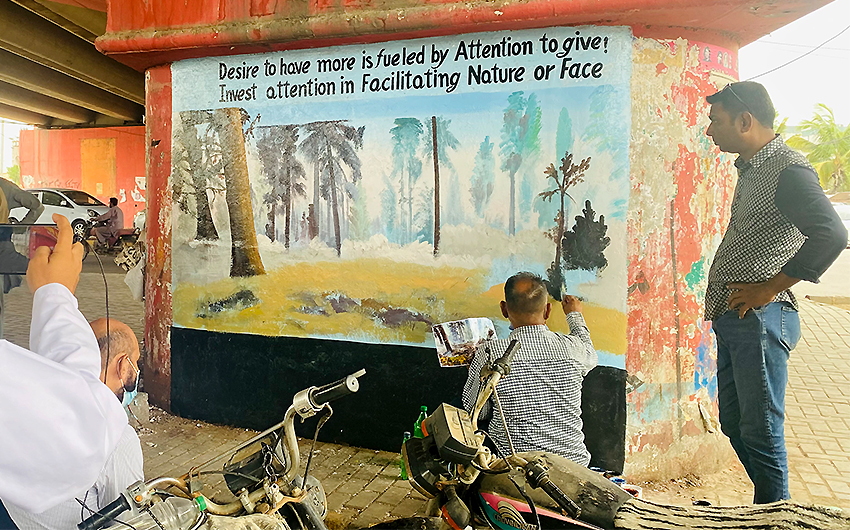

KARACHI: A Pakistani artist on Tuesday scratched advertising posters from a pillar supporting a busy flyover in the port city of Karachi, and then began painting “a mural with a message” over the palimpsest.

Iqbal Sanam, a renowned truck artist who has painted murals around the world, including on the Berlin Wall, believes he can use his art to create awareness about social issues. These days, he wants to remind his fellow residents of Karachi about the dangers posed by climate change.

“This mural not only has trees but also plumes of smoke that are spreading across the jungle, endangering its greenery and wildlife,” Sanam told Arab News, describing the painting he was working on. “Its message is to preserve nature and protect forests and trees.”

“A painting with a message educates many,” the artist added. “We are reaching out to students, our future generation, along with the general public with the message of environmental protection since that can benefit our loved ones and the world at large.”

Jawad Ali, who works at a local hospital, takes photos of a mural near Karachi’s Civic Center, Pakistan, on July 27, 2021. (AN Photo)

Tariq Khan, a director of the Sadequain Foundation, said Sanam’s mural was part of an initiative to paint bus stops, flyovers and education institutions with colorful artwork that would create awareness and lead people to reflect on the perils of climate change.

“The first in the series of these murals was painted on a wall of Sir Syed Girls’ College about two days ago,” Khan said. “That depicted the adverse effect of climate change by highlighting how the melting of glaciers recently flooded parts of Germany.”

Another mural with a climate change message would next be painted near a crowded traffic signal at Ayesha Manzil, a busy area in Karachi, Khan said: “We have chosen places that are visited by large numbers of people to create greater awareness.”

People look at a mural showing melting glaciers and floods that was recently painted on a wall of Sir Syed Girls’ College in Karachi, Pakistan, on July 27, 2021. (AN Photo)

Jawad Ali, who works at a local hospital, stopped to have a look at Sanam’s painting on his way to work.

“Deforestation can have a drastic impact on our lives,” he told Arab News. “People should ponder over the message of this mural.”

Yousuf Rehman, who drives an autorickshaw, also pulled over to study the mural.

“It is soothing to see such beautiful paintings,” he said, “instead of provocative slogans and ugly posters on the walls.”