WELLINGTON: Tentative plans for a movie that recounts the response of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern to a gunman's slaughter of Muslim worshippers drew criticism in New Zealand on Friday for not focusing on the victims of the attacks.

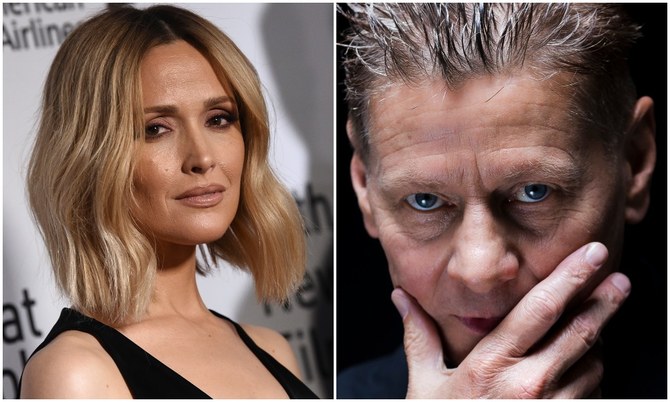

Hollywood news outlet Deadline reported that Australian actor Rose Byrne was set to play Ardern in the movie “They Are Us,” which was being shopped by New York-based FilmNation Entertainment to international buyers.

The movie would be set in the days after the 2019 attacks in which 51 people were killed at two Christchurch mosques.

Deadline said the movie would follow Ardern's response to the attacks and how people rallied behind her message of compassion and unity, and her successful call to ban the deadliest types of semiautomatic weapons.

The title of the movie comes from the words Ardern spoke in a landmark address soon after the attacks. At the time, Ardern was praised around the world for her response.

But many in New Zealand are raising concerns about the movie plans.

Aya Al-Umari, whose older brother Hussein was killed in the attacks, wrote on Twitter simply “Yeah nah,” a New Zealand phrase meaning “No.”

Abdigani Ali, a spokesperson for the Muslim Association of Canterbury, said the community recognized the story of the attacks needed to be told “but we would want to ensure that it’s done in an appropriate, authentic, and sensitive matter.”

Tina Ngata, an author and advocate, was more blunt, tweeting that the slaughter of Muslims should not be the backdrop for a film about "white woman strength. COME ON.”

Ardern’s office said in a brief statement that the prime minister and her government have no involvement with the movie.

Deadline reported that New Zealander Andrew Niccol would write and direct the project and that the script was developed in consultation with several members of the mosques affected by the tragedy.

Niccol said the film wasn't so much about the attacks but more the response.

“The film addresses our common humanity, which is why I think it will speak to people around the world," Niccol told Deadline. "It is an example of how we should respond when there’s an attack on our fellow human beings.”

Byrne's agents and FilmNation did not immediately respond to requests for comment. The report said the project would be filmed in New Zealand but did not say when.

Niccol is known for writing and directing “Gattaca” and writing “The Terminal" and “The Truman Show,” for which he was nominated for an Oscar.

Byrne is known for roles in “Spy” and “Bridesmaids.”

Plans for movie on New Zealand mosque attacks draw criticism

https://arab.news/bcjmt

Plans for movie on New Zealand mosque attacks draw criticism

- The movie would be set in the days after the 2019 attacks in which 51 people were killed at two Christchurch mosques

Decoding villains at an Emirates LitFest panel in Dubai

DUBAI: At this year’s Emirates Airline Festival of Literature in Dubai, a panel on Saturday titled “The Monster Next Door,” moderated by Shane McGinley, posed a question for the ages: Are villains born or made?

Novelists Annabel Kantaria, Louise Candlish and Ruth Ware, joined by a packed audience, dissected the craft of creating morally ambiguous characters alongside the social science that informs them. “A pure villain,” said Ware, “is chilling to construct … The remorselessness unsettles you — How do you build someone who cannot imagine another’s pain?”

Candlish described character-building as a gradual process of “layering over several edits” until a figure feels human. “You have to build the flesh on the bone or they will remain caricatures,” she added.

The debate moved quickly to the nature-versus-nurture debate. “Do you believe that people are born evil?” asked McGinley, prompting both laughter and loud sighs.

Candlish confessed a failed attempt to write a Tom Ripley–style antihero: “I spent the whole time coming up with reasons why my characters do this … It wasn’t really their fault,” she said, explaining that even when she tried to excise conscience, her character kept expressing “moral scruples” and second thoughts.

“You inevitably fold parts of yourself into your creations,” said Ware. “The spark that makes it come alive is often the little bit of you in there.”

Panelists likened character creation to Frankenstein work. “You take the irritating habit of that co‑worker, the weird couple you saw in a restaurant, bits of friends and enemies, and stitch them together,” said Ware.

But real-world perspective reframed the literary exercise in stark terms. Kantaria recounted teaching a prison writing class and quoting the facility director, who told her, “It’s not full of monsters. It’s normal people who made a bad decision.” She recalled being struck that many inmates were “one silly decision” away from the crimes that put them behind bars. “Any one of us could be one decision away from jail time,” she said.

The panelists also turned to scientific findings through the discussion. Ware cited infant studies showing babies prefer helpers to hinderers in puppet shows, suggesting “we are born with a natural propensity to be attracted to good.”

Candlish referenced twin studies and research on narrative: People who can form a coherent story about trauma often “have much better outcomes,” she explained.

“Both things will end up being super, super neat,” she said of genes and upbringing, before turning to the redemptive power of storytelling: “When we can make sense of what happened to us, we cope better.”

As the session closed, McGinley steered the panel away from tidy answers. Villainy, the authors agreed, is rarely the product of an immutable core; more often, it is assembled from ordinary impulses, missteps and circumstances. For writers like Kantaria, Candlish and Ware, the task is not to excuse cruelty but “to understand the fragile architecture that holds it together,” and to ask readers to inhabit uncomfortable but necessary perspectives.