SHARJAH: The successful entry of the UAE’s Hope probe into orbit around Mars is a historic event on the scientific, educational, and strategic levels. Indeed, for the first time ever, an Arab nation has gone beyond applied space science and technology (satellites, essentially) and successfully invested and engaged in space exploration.

It is important to underline the mission’s wider and embracing slogan, “Arabs to Mars,” which stresses the idea that this project is greater than just the UAE joining a select club of space-faring nations. It is about leading the Arab world into deep space, into the future.

Now that Hope probe is set for its scientific agenda and the UAE is set to become a science-producing nation in the space arena, it is important to reflect on the significance of this event for the Arab world and the vistas that it opens for its people.

As great as the scientific agenda of the mission is (providing in-depth, close-up, and global explorations of the Martian atmosphere), the impact that this is likely to have on the Arab world, particularly its ambitious youth, will be multifaceted and strong.

Emirati men are pictured at the mission control center for the "Hope" Mars probe at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre in Dubai on July 19, 2020, ahead of its expected launch from Japan. (AFP/File Photo)

Indeed, this quantum-leap event tells Arabs — or at least this is how it should be understood — that science is the way to the future, and Mars (with all the scientific and technical know-how that will have been acquired) is simply a springboard to that future.

Since the launch of Hope, last July, followed by the Chinese mission to Mars, Tianwen-1, and the American one, Mars 2020, I have noticed an important change in the views expressed by many Arabs and people in the region.

Until then, most people seemed bewildered by the “wasteful” Hope mission (although $200 million is really not much for such a big endeavor) and often asked “what’s the benefit in there?”, “why don’t you spend money helping the poor around the world.”

Indeed, the utilitarian standpoint is so prevalent in the Arab world that last July, two weeks before the launch of Hope, I took part in a panel titled “Why spend money on space science?”, a question I am asked time and again.

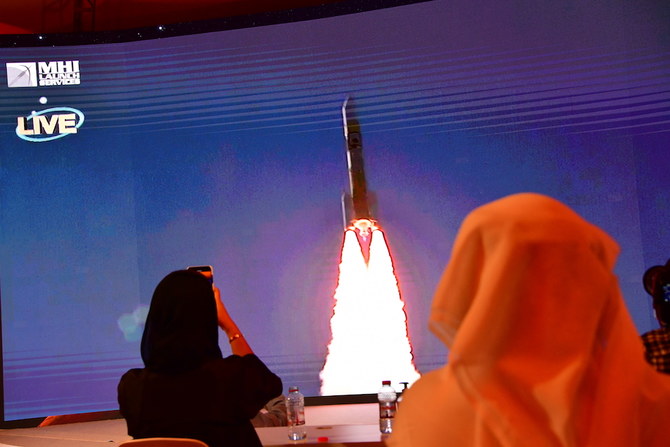

H-2A rocket carrying the Hope Probe, known as "Al-Amal" in Arabic, developed by the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to explore Mars, blasts off from Tanegashima Space Centre in southwestern Japan. (AFP/Mitsubishi Heavy Industries/File Photo)

My reply, depending on my interlocutors or audience, usually revolves around the following points. First, before anyone criticizes space-science budgets (a grand total of roughly $50 billion in the whole world, averaging $6.5 per year for each human being), they should take a look at military budgets ($1,750 billion worldwide in 2019, 35 times more than the worldwide space budget).

Secondly, space science brings many direct benefits (think of all the applications of satellites, starting with GPS, which each of us uses almost every day) as well as indirect ones, as we explore, discover, learn, widen our horizons, and think of new things.

Last but not least, space is a field that fascinates people, especially youngsters, and leads them to embark on various exciting careers that benefit their nations and the world at large.

READ MORE: UAE’s ‘Hope’ probe sends home first image of Mars

UAE Hope Probe expected to provide first complete picture of Mars in one week

Interestingly, since the launch of Hope, I have been hearing the “why waste money on Mars and in space” viewpoint less often. Surveys on attitudes toward science, technology, and space are being conducted in the region, and it will be highly interesting to see how those attitudes have evolved recently and will evolve in the future.

It is worth noting that in the decade following John Kennedy’s “to the moon” announcement, the number of Ph.D. holders in the US tripled in the physical sciences and quadrupled in engineering. And a 2009 survey found that 50 percent of the internationally renowned scientists who have published in Nature (the premier scientific research journal) had been inspired to become scientists by the US moon program.

I am convinced that the Hope mission will have a similar effect in the Arab world. We are already seeing such results in the UAE, where the number of students who are choosing physics, astronomy, and space has increased manifold in recent years.

Visitors watch an air craft maintenance competition during the "World Skills" International competition in Abu Dhabi on October 18, 2017. (AFP/File Photo)

If the Hope mission produces that kind of educational effect in the wider Arab world, it will be a magnificent, transformative achievement that historians will be discussing for decades or even centuries.

In fact, I believe that the project can achieve even greater objectives than that lofty educational goal. It could also lead to a quantum leap in science and technology production in the Arab world.

How could that be achieved? First, Arab scientists, decision makers, and opinion makers need to embrace the “basic” (that is, not applied) type of science and knowledge that space exploration represents. Simply put, Arab countries cannot become “developed” by limiting their development to applied fields; technology goes hand in hand with science, and with broader knowledge.

It is not a coincidence that astronomy (which has little if any direct applications in our everyday lives) was the first big science to blossom and flourish during the Arab-Islamic civilization and the last one to wane. And yet, today, the number of properly operating and science-producing astronomical observatories in the entire Arab world can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Most Arab countries have locations and weather that favor the erection of astronomical observatories, which are not very expensive; this should be pursued promptly and in earnest.

Likewise, several Arab countries, particularly the UAE and Oman, are geographically well placed (low latitude, sea or ocean to the east, etc.) to host space rocket launch facilities. This could be one of the next projects to embark on, to build platforms from where to launch both our own rockets and those of others (for profit).

A handout picture provided on February 14, 2021 by the United Arab Emirates Space Agency (UAESA) taken by the Emirates eXploration Imager (EXI) after Mars Orbit Insertion (MOI) on board the First Emirates Mars Mission (EMM) from an altitude of 24,700 km above the Martian surface shows the Olympus Mons, the highest volcano on Mars, and the Tharsis Montes, three volcanoes named (top to bottom) Ascraeus Mons, Pavonis Mons and Arsia Mons. (AFP/File Photo)

Moreover, as we have seen with NASA for the last 60 years or so, technological spin-offs from space programs can be adopted and applied in other areas of life and economy, such as medical facilities, transportation, telecommunications, and more.

Last but not least, the new Arab space strategy (at least six states have space agencies now) should lead to important reviews of Arab educational programs. Universities must revisit, update, and upgrade their curricula, including the creation of new departments and specializations (space science, artificial intelligence, etc).

It is not acceptable, or even logical, for the Arab world to have half a dozen space agencies but fewer space-science departments and specialized programs.

We urgently need to train students in both applied space science (for example, remote sensing) and astronomy (Mars and beyond), to support and complement the work of the Arab space agencies. In fact, we need a wider update and revamping of higher-education programs in the Arab world, but that is another discussion.

The Hope mission to Mars can be truly transformative if everyone aims high and believes that science is the key to a knowledge-based economy and future. Let us use this historic event to rebuild Arab scientific, technological, and educational institutions, to strengthen national, regional and international collaborations, and to give Arab youngsters a vision and plan for a bright future.

---------------------

Nidhal Guessoum is a professor of physics and astronomy at the American University of Sharjah. Twitter: @NidhalGuessoum