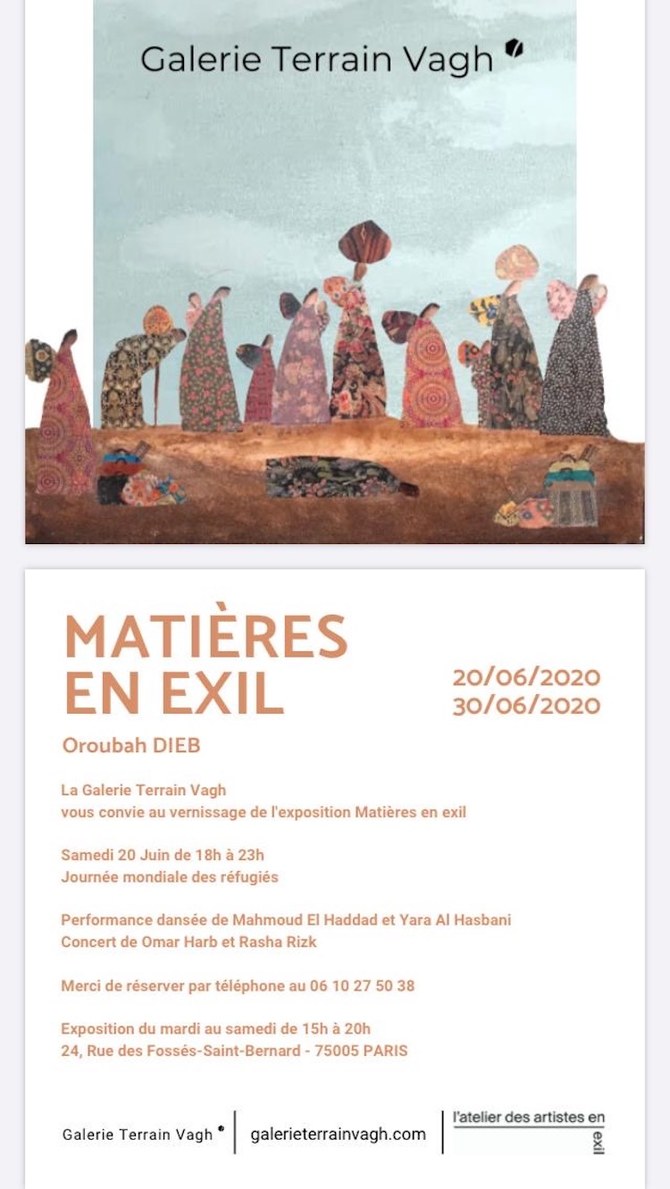

PARIS: To mark World Refugee Day, “Materials in Exile,” an exhibition of work by Syrian sculptor and painter Oroubah Dieb, will open at Galerie Terrain Vagh in Paris on June 20.

The artist left Damascus in 2012, seven years after founding a private art school in the city with her husband, Hammoud Shantout, who is also a painter and sculptor.

“We were the first to establish a private fine arts school for children and adults in Syria,” said Dieb. “We worked with schools and universities, and sponsored numerous exhibitions and activities.

“We launched the project seven years before we were forced to leave Syria. In 2012 we had to close the school and move to Lebanon due to the war that was ravaging the country. We could no longer remain, with our three girls, in our country and we could not take part in this war so we left Syria when our lives became impossible. We had to give up very good jobs and a comfortable life to go to Lebanon and France, where we have had to change our lives completely.”

Since leaving Syria, Dieb has worked to help refugees. In Lebanon, she taught art to children in the Khiara refugee camp. She has also worked with Syrian humanitarian and relief foundation Najda Now International, which has set up projects in Sabra and Shatila camps, which were originally set up for Palestinian refugees. They have a resident psychoanalyst, Dr. Yasser Moalla, and Dieb’s daughter Nour Shantout, who was studying at the Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts, an architectural university in Beirut.

“We were working in the camp on how to remedy the effects of war on children through the arts,” said Dieb. “We held many exhibitions at the French Embassy in Lebanon and also in downtown Beirut. There are Syrian refugees who have settled in the Sabra and Shatila camps and we worked with them.”

Dieb is currently working at the Artists in Exile workshop in Paris and participates in art events across Europe. Her work has been displayed around the world in Beirut, Dubai and many other cities. She said that much of her art embodies the experience of living in exile that refugees are forced to face. Her paintings depict the dramatic situations they encounter, and their suffering and misery.

“In my case, I was lucky enough to leave with my family on a plane when my daughter was already in France,” she said. “I had many acquaintances, so my situation was really very good compared with others.

“Still, the exile was a disaster for me because I had to give up everything I had worked for with my husband for 45 years in Syria. We arrived in France where no one knew us and where we had nothing but worries. This is my suffering — and I am well aware of the much greater drama and misery of millions of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.”

Materials in Exile by Oroubah Dieb will be at Galerie Terrain Vagh in Paris from June 20 to 30. The show has been organized by the gallery’s owners, Tunisian artist Moufida Atig and Judith Depaule of the Craftsmen’s Workshop.

The opening on June 20 will be accompanied by a series of events at the gallery, including performances by acclaimed Syrian singer Racha Rizk and young Syrian guitarist, Omar Harb, and a dance display by Mahmoud Al-Haddad from Egypt and Yara Hasbani from Syria. All of the day’s events will focus on the plight of refugees.