CAIRO: “The Knight and the Princess,” Egypt’s first animated feature film, created by a Saudi company, recently had its world premiere at the third edition of the El Gouna Film Festival and will soon make its way to the 9th Malmo Arab Film Festival in Sweden.

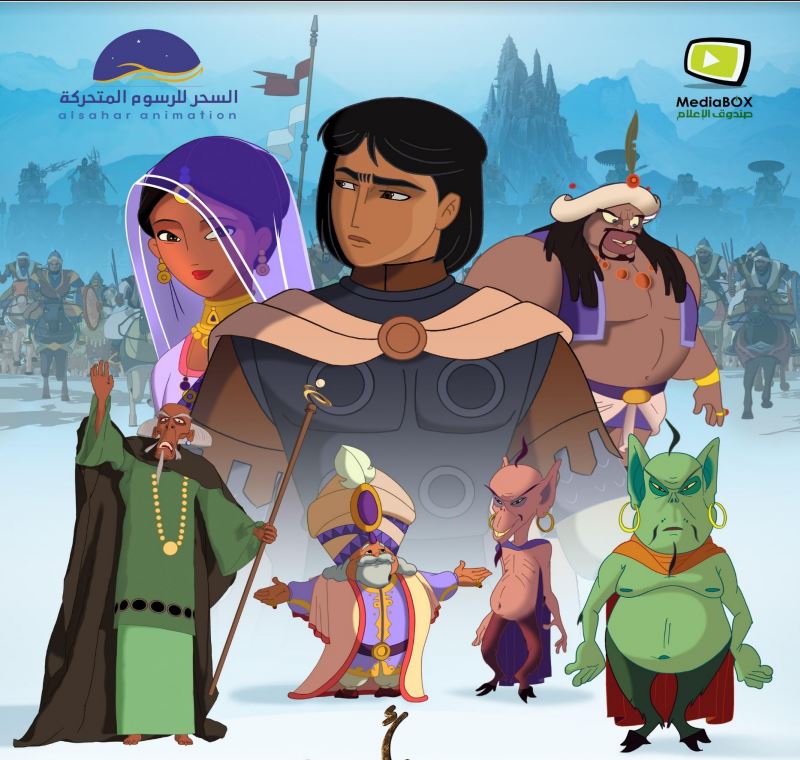

Scripted and directed by prominent screenwriter Bashir El-Deek and co-directed by Ibrahim Mousa Mostafa, with character designs by late cartoonist Mustafa Hussein, this long-awaited action-adventure animated comedy is the latest production from leading Saudi-led animation company, Alsahar Animation.

The animation is a fictionalized account of the adventures of 7th century Basra-born warrior Mohammed Bin Alkassim, who at the age of 15 sets off to save women and children abducted by pirates from merchant ships in the Indian Ocean. His heroic adventures ultimately bring him face to face with king Daher, the tyrannical ruler of North India, and his treacherous sorcerer, Gandar.

The film features a star-studded voice cast, including Egyptian mega stars Medhat Saleh, Donia Samir Ghanem, Mohamed Henedy, Maged El-Kedwany, Abdel Rahman Abou Zahra, Abla Kamel and Lekaa Elkhamissi.

“The Knight and the Princess” was born of a dream to tell an Arab story featuring a real Arab hero and is premised on the belief that “Arab stories are better told from an Arab perspective by Arab talents,” according to the press release.

“From the start, when we decided to produce an animated feature, our aim was that the story has to come from our culture, and (be) done by Arab artists,” Alabbas Bin Alabbas, founder and president of Alsahar Animation, told Arab News.

“It is self-expression of our history and culture and artistic point of view. We felt we have something to convey to our society and the world at large. Making a decent and respectful effort to tell our story from our perspective was the right thing to do,” he added.

Telling these kinds of stories, Alabbas believes, will “naturally...face off with the stereotypes the West intentionally (pushes).”

Alabbas’s Cairo-based company has built its reputation over the past three decades producing children’s animated series.

Established by Alabbas in 1992 as the Arab region’s leading animation production company, the enterprise was inspired by a personal encounter he had years earlier.

‘The Knight and the Princess’ recently had its world premiere at the third edition of El Gouna Film Festival. (Getty)

“When I was in the US during my PhD program, my son was five-years-old, I was surprised by the great impact of the animation series he was watching,” Alabbas explained.

“I decided to travel to Egypt to get a few Arabic TV animation series and to my surprise I discovered there was no animation in Egypt or the Arab world,” he said.

This was Alabbas’s cue to switch careers from engineering and computer science and delve into the world of animation production, establishing his production company soon after graduation.

“After eight years and many animated TV series, we felt the urge to take on a bigger challenge and be free of the restrictions and limitations requested by TV stations,” Alabbas said of why he decided to create the new film.

Growing more confident in his company’s animation abilities, Alabbas felt the time was ripe for the company’s first animated feature and approached screenwriter Bashir El-Deek with the idea.

“The Knight and the Princess” is Egypt’s first animation feature film. (Supplied)

It wasn’t smooth sailing, however.

“The quality demands of an animated feature film far exceed the limited animation styles fit for animated TV series,” Alabbas said.

“So, we had to train more talents and develop the experience of all talents to outperform themselves. I was determined not to present the film with excuses of our lack of experience.”

It was in the process of training animators that Alabbas and his crew ended up building a competent local industry.

“We meant to produce the film and ended up building the animation industry in the Arab world,” he says.

Now that the film is finally hitting the big screen, Alabbas has reason to be optimistic about the future of the Arab animation industry.

“The successful result of our production puts a lot of pressure on everyone in the Arab world — they have no excuse not to venture into this important and vital industry,” he said.

“The ball (is now in the court of) those who used to say we need to do something for our new generations that makes them proud of their heritage.”

“The Knight the Princess” is due to have its European premiere at the 9th Malmo Arab Film Festival, which runs from Oct. 4-8, and is sure to enchant international audiences.