ABU DHABI: In the age of the social media influencer, the phenomenon and the power of “likes” have been driving brands to sign up a handful of users for huge sums to reach out to the masses.

A single post or a picture by an “influencer” — such as a fitness guru, beauty blogger or fashion expert — can rake it in. In the Middle East, such elite users command astronomical fees with their appeal to a region that is home to a digitally empowered Arab youth.

But as with any lucrative business, fraud has followed.

Influencer fraud, in which celebrities acquire fake followers to create fake personas on platforms such as Instagram to inflate their fan base, is expected to cost businesses $1.3 billion (SR4.8 billion) this year, according to research from cybersecurity firm Cheq. The study found that at least 15 percent of all influencers’ followers were fake.

“It’s a huge waste,” said economist Roberto Cavazos, a University of Baltimore professor who conducted the analysis for Cheq, noting that his estimate is conservative.

Companies worldwide spend an estimated $8.5 billion annually to persuade influencers to market their products, according to Mediakix, an influencer-marketing firm.

Cavazos estimates about 15 percent of the corporate dollars spent daily are lost to influencer fraud.

He said the phenomenon of “vanity metrics” explains why many marketing companies have welcomed the recent move by Instagram to crack down on influencer fraud.

Fake accounts are banned on Instagram, which is owned by Facebook, and the company has recently started testing a design tweak that will no longer show the total number of “likes” other users’ posts have received.

Initially launched in Canada, it also being rolled out to users in six other countries: Ireland, Italy, Japan, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand.

Since the advent of social media, business marketing has gone through an overhaul, with the focus increasingly on billions of online users.

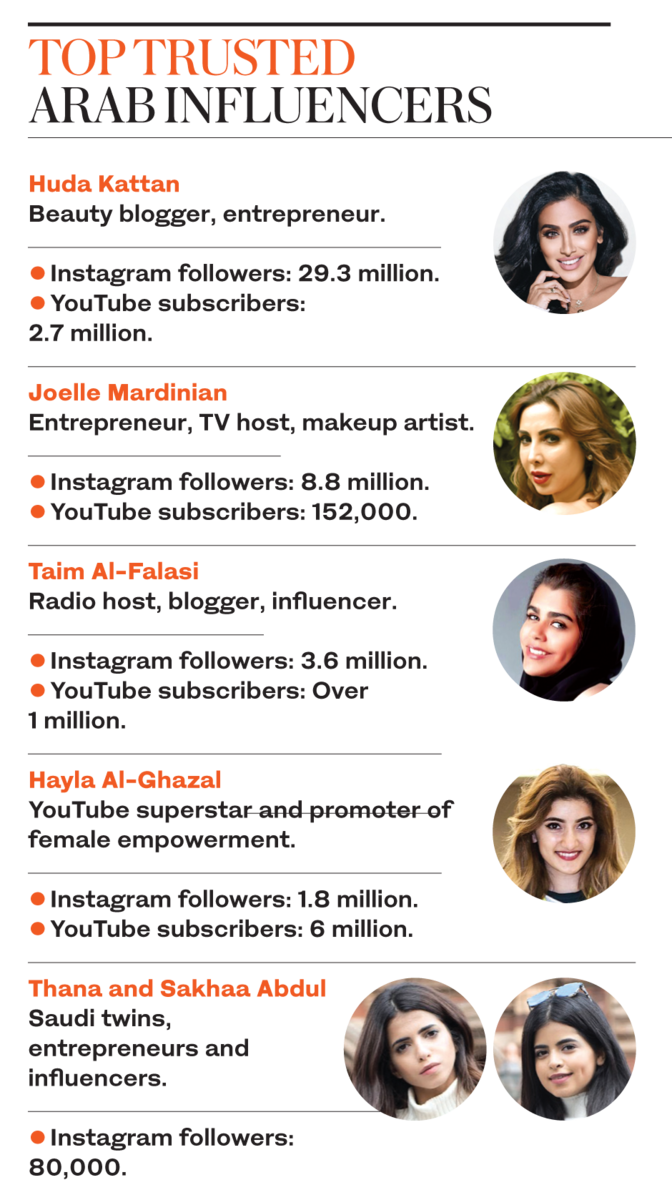

In Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, social media influencers have become one of the most important marketing tools for businesses to enhance awareness of their brands. In the Arab world alone, there are about 164 million active Facebook users, in addition to more than 200 YouTube channels with over a million subscribers.

Around 30,000 Middle East-based YouTubers have more than 10,000 followers. There are also about 12 million daily Snapchat users in the GCC, including 9 million in Saudi Arabia and 1 million in the UAE.

Kirsty O’Connor, director of content and publishing at Hill+Knowlton MENA, said the transformation of business marketing has allowed fake influencers to take advantage of brands’ desire to engage a young MENA audience online.

Influencer fraud can be described as a “social media publisher deceiving a brand or partner into thinking they are reaching and engaging with an audience that is not there,” she said.

The most common fraud, said O’Connor, is fake followers, or “bots,” including engagement that involves paying a “bot farm” — a computer robot — to mass “like” pages or posts.

Within the Middle East, O’Connor said influencer fraud is far easier to detect than in Western markets.

“Marketers and communicators have played their part in this, by first starting to benchmark influencers based on their follower number or engagement rate. ‘How many followers do they have?’ was — and still can be — a measure to decide whether to engage with an influencer, which for me needs to be stamped out.”

According to Aaron Brooks, co-founder of Middle East-based mobile content and influencer marketing platform Vamp, for anyone close to the influencer-marketing industry, “fake followers are old news.”

“It’s something platforms like Vamp, and Instagram itself, have been cracking down on for years,” he said. “The fact that someone has slapped a valuation on its impact has only brought the issue back in focus.”

Brooks says brands rely on “reach” for their products, even though this is an outdated metric.

“But marketers are still plowing their money into influencers with large followings, without doing due diligence on whether they are actually real, and are likely to be losing money,” he told Arab News.

“Fake followers cannot deliver a return on investment. Brands should also be aiming higher when it comes to the results of an influencer-marketing collaboration.”

He is clear about the way out: “Unless a campaign’s success hinges solely on visible engagement, nothing much will change,” he said. “What will change is the industry’s need to focus on solid return on investment to justify itself.”

According to O’Connor, the pressure on influencers to have millions of followers results in large bot followings in the region.

“The issue with a bot following is they are not real, so they don’t engage with your content like a human would, giving you a low number of ‘likes’ or comments on posts,” she said.

“Influencers then need to buy their ‘likes’ and comments to keep their following vs engagement percentage attractive to marketers.”

This becomes a cycle of buying fake followers, O’Connor said, adding that no influencer should be paid large amounts without sharing legitimate data about their following.

Experts have said they can identify fake accounts using several indicators. Takumi, a marketing agency, said these included large groups of followers, such as a 15,000 batch of fans following overnight. Other signs are large followings from countries such as India, Brazil and Mexico, “where bot farms are commonly located.”

O’Connor said an interesting development for the Middle East was the introduction by the UAE in January of an “influencer license.” All social media influencers must now have a license from the UAE’s National Media Council if they are commercializing their page.

“This is a great move to regulate influencers while also holding them accountable to local media and advertising laws,” she said. “It is similar to the US and UK where influencers have to disclose paid-for work as advertising to meet standards and protect the consumer.”

In January, the UAE introduced an “influence license,” which social media users must have before they commercialize their pages.

(Shutterstock)

“I hope to see this rolled out into other Middle East markets to ensure unity across influencer-marketing regulations.”

O’Connor said that Instagram’s recent move strengthens her belief that counting followers and “likes” to measure influencers is no longer viable.

“There should be a lot of focus on how we measure our work with influencers, and also pressure on influencers and Facebook to share their data before, during and after campaigns.

“Removing ‘likes’ from posts will make it harder to spot fake followings as this will amount to hiding a key engagement metric.”

O’Connor said that the role of influencers is far from over, but is in a state of “evolve or die.”

Brooks agrees, but cautions that all social media influencers should not be tarred with the same brush.

“Luckily, there are so many amazing influencers to partner with,” he told Arab News. “There are just as many creative, professional and authentic influencers as there are wannabes with falsely inflated followings. A considered selection process is key.”

A genuine following should be the minimum requirement for brands partnering with influencers.

“Advanced analytics can now tell a brand where an influencer’s following is based and how old they are, so marketers can target their customers with precision.

“Relevance is essential for an effective campaign. Brand ambassadors have been — and will always be — an effective marketing tactic,” he said.