GWADAR: It was a still night sometime in the mid fifties when Muhammad Akbar and his father returned from sea and anchored their boat on the tiny jetty in Gwadar. Behind them, fireworks lit up the sky, reminding them that the religious festival of Eid had begun.

That is how Eid used to be officially announced in Gwadar until 1958 when the Pakistan government purchased the tiny fishing town from Oman for Rs5.5 billion (current equivalent of $3.89 billion), Akbar, now 78, told Arab News.

Arab soldiers of Oman seen in a photo handout by Gwadar resident Nasir Raheem.

“When Gwadar became a part of Pakistan, the ritual stopped being practiced,” he said as he sipped tea at the historic Kareemuk Hotel, formerly a bakery owned by an Arab businessman who gifted it to a local who has since converted it into a tea shop.

China has funded development of a deepwater port at Gwadar in the southern Balochistan province, and is also investing in other projects as part of the giant China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). In February, Saudi Arabia announced it would build a $10 billion refinery and petrochemicals complex in the coastal town.

But even as Gwadar grows from a poor coastal village into a major port city, the Arab legacy lingers.

This photo taken on Tuesday April 23, 2019 shows one of three Omani forts in Gwadar, which was part of the Sultanate of Oman until September 1958. (AN Photo by Hassam Lashkari)

The town is situated on a sandy 12-kilometer-long strip that links the Pakistani coast to rocky outcroppings in the Arabian Sea known as the Gwadar Peninsula, or Koh-e-Batil.

In 1783, the Khan of Kalat Mir Noori Naseer Khan Baloch granted suzerainty over Gwadar to Taimur Sultan, the defeated ruler of Musca. The sultan continued to rule over the territory through an administrator even after reclaiming Muscat.

From 1863 to 1879, Gwadar was the headquarters of a British administrator, a fortnightly port of call for the British India Steamship Navigation Company’s steamers and included a combined Post and Telegraph Office. The Sultan remained the sovereign of Gwadar until negotiations were held with the government of Pakistan in the 1950s.

This cannon displayed outside the old municipal office of Gwadar is one the two cannons which would fire explosives to announce the beginning of the religious festival of Eid before Pakistan purchased Gwadar from Oman in 1958, locals told Arab News on Tuesday, April 23, 2019 (AN Photo by Hassam Lashkari)

Today, officials say over 2,000 of Gwadar’s 140,000 residents are dual Pakistani and Omani nationals. Many people from Makran district, of which Gwadar is a part, serve in the Omani army and the Bahraini police. A large number continue to work in Oman, Qatar, UAE and Bahrain and send remittances back home.

Of the three forts built during Omani rule, one was restored and turned into a museum by Oman’s ministry of heritage and culture and officially inaugurated by former Pakistani military ruler General Pervez Musharraf on March 20, 2007.

“My brother works in Oman, my sister is an Omani national,” said Nasir Raheem, a social activist, whose father Raheem Bux Sohrabi campaigned for Gwadar’s accession to Pakistan. “This is the story of every second household and it connects us to the Arab world.”

On April 23, 2019, Sakeena Bibi, 80, recalled "the golden days" of Gwadar before Pakistan purchased the town from the rulers of Oman in 1958 (AN Photo by Hassam Lashkari)

Septuagenarian Akbar pointed to the cannons outside the town’s old municipal office. “They are not fired anymore to announce the advent of Eid,” Akbar said. “But we still break our fasts in the month of Ramadan much like the Arabs do.”

Unlike the rest of Balochistan, the people of Gwadar have dates and lassi, a cold drink of yogurt and water, at the traditional sundown iftar meal in the fasting month of Ramadan, and eat their dinner after evening tarawih prayers. In many homes, dates are softened in water and mixed with wheat flour to prepare the Arab dish of Sakoun, which is then distributed among family members and neighbors.

“In the olden days, women started preparing Sakoun at noon and would send it to neighbors homes a few hours before iftar,” Raheem, the social activist, said.

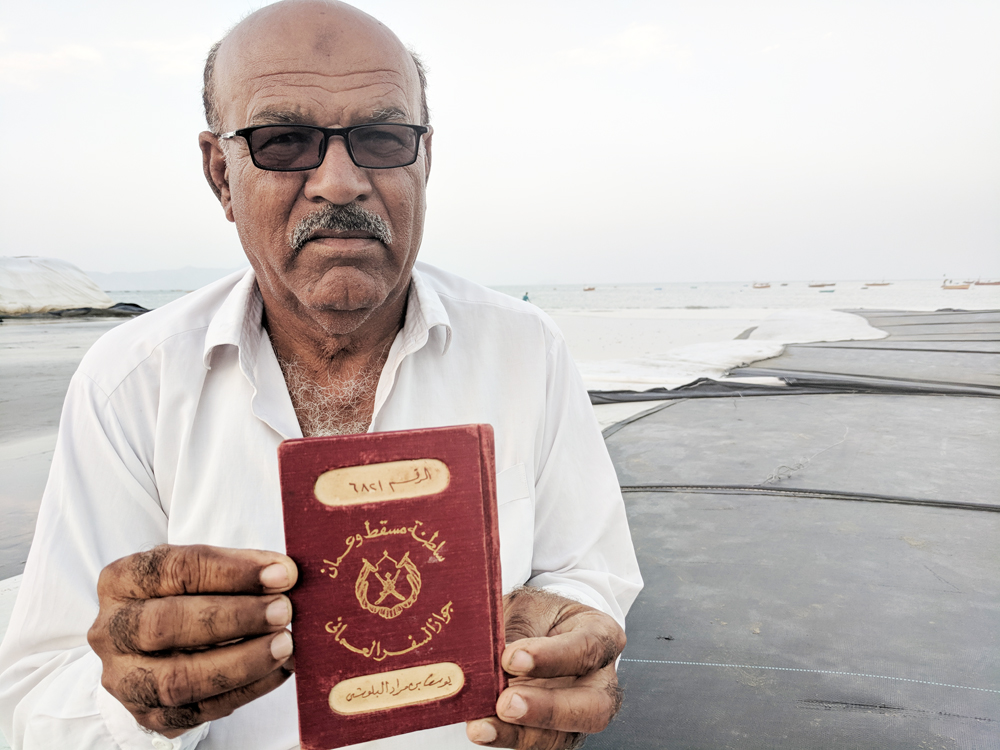

Dad Kareem, a fisherman who has kept the old Omani passport of his father, told Arab News on Tuesday, April 23, 2019 that the people of Gwadar have a special love for Arabs (AN Photo by Hassam Lashkari)

Sakeena Bibi, 80, said women in Gwadar still practiced many Arab traditions.

“They like to use oud scent,” she said. “Oud is put on flaming coals and the smoke is then spread in wardrobes to give clothes a long lasting fragrance.”

Whenever relatives in Oman or other Gulf countries asked about gift options, the women of Gwadar asked for oud, Bibi said.

The people of Gwadar have also taken inspiration from Leva, an African and Arab dance routine in which a man beats a drum and people dance around him. Many residents still wear the long kandura robe on special occasions like weddings, Eid and Friday prayers.

This photo taken on Tuesday April 23, 2019 shows a Omani fort in Thana Ward in Gwadar, which has now been converted into museum. (AN Photo by Hassam Lashkari)

Dad Karim, a fisherman who like many older residents of the town still has his parent’s old Gwadar passport from the 1900s, said the people of Gwadar could tolerate criticism of Pakistan’s government “but get annoyed when someone says something against the rulers of Oman.”

“When someone from a foreign country rules another population, the locals begin to despise them,” Karim said. “Ours is a special case. There is love and only love.”