RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil: From the outside, it looks like another historic edifice in Rio’s rundown city center.

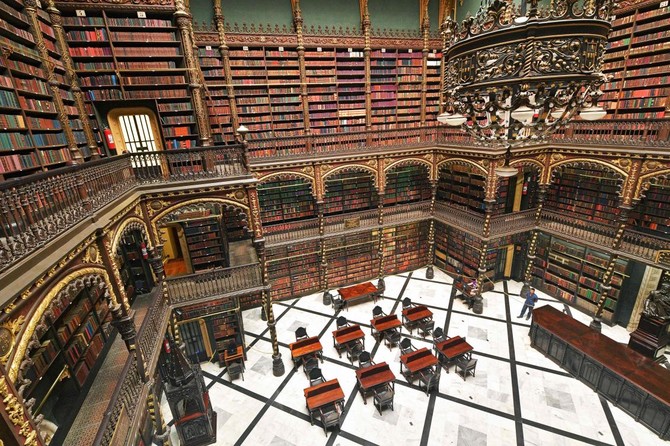

Inside, however, is a multi-tiered library so spectacular, so ornate, that stunned visitors feel like they’ve walked into a movie fantasy set.

“In ‘Harry Potter’ we’ve seen libraries like this!” exclaimed Didier Margouet, a 57-year-old French tourist, looking around at the shelves of leather bound books climbing the walls under an octagonal skylight of red, white and blue stained glass.

“Yes, like in the movies,” agreed his partner, Laeticia Rau, 50.

The Royal Portuguese Reading Room — the Real Gabinete Portugues de Leitura in Portuguese — was built in the late 19th century under the stewardship of an association of Portuguese migrants that still cares for the institution.

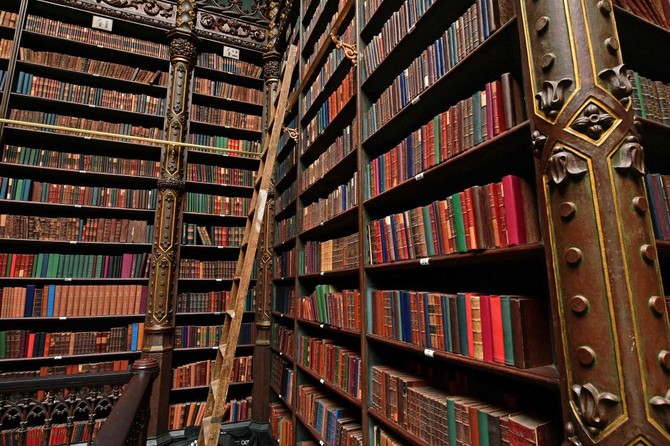

Its Gothic-Renaissance architecture and plethora of carvings, tiles and sculptures celebrate the glory of the Portuguese discoveries era in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Holding some 350,000 books, some of them very rare, the library today is more a tourist attraction and selfie backdrop than a reading room, though for a few it remains an indispensable haven for the largest collection of Portuguese-language books outside of Portugal.

One such loyal reader is Carlos Francisco Moura, an 86-year-old who writes about the history of Portugal.

He arrived in Brazil from Portugal aged four with his parents, and from childhood became a regular visitor. Now retired from his profession as architect, Moura spends his time leafing through the tomes, copying information for his own books.

“This is the alma mater of the Portuguese in Brazil — the reading room is that, and a lot more,” Moura told AFP, sitting at one of the dark wooden desks.

The library is a valuable resource, he explained, because since the 1930s it has become a repository of every book published in Portugal.

Brazil’s historic connection with its former colonial ruler runs deep. In 1808, Portugal’s king and his government made Rio de Janeiro the capital of the Portuguese Empire.

Later, the king’s son declared independence and made himself the emperor of Brazil. Portuguese remained the country’s principal language, and with it a two-way literary culture between the two countries. Today, the Portuguese and Brazilian flags both fly on the library’s exterior.

Orlando Inacio, 67, manages the place. He too came from Portugal as a boy — and has never returned.

“It’s a real point of pride to know that this library created by Portuguese is one of the most beautiful in the world,” he said.

Giving a bit of its history, he traced the library’s roots back to an association of Portuguese immigrants started in 1837.

“The aim was to help the immigrants, who in general were little educated, to improve their knowledge, their education,” he said.

The association continues to fund the library, its members paying a monthly amount that helps cover part of its overheads. The rest of the income comes from other buildings owned by the association that are rented out.

Inacio acknowledged that the Internet has brought changes, reducing the need for researchers and bookworms to frequent the place except for consulting rare books that are otherwise unavailable.

But his delight in his everyday office is evident. He is, after all, custodian of a temple of literature steeped in history, connecting Portugal and Brazil in a bond of language.

Historic library weaves ‘Harry Potter’-style tourist magic in Rio

Historic library weaves ‘Harry Potter’-style tourist magic in Rio

- The Royal Portuguese Reading Room was built in the late 19th century

- The library is a valuable resource because since the 1930s it has become a repository of every book published in Portugal

From historic desert landscapes to sound stages: AlUla’s bid to become the region’s film capital

DUBAI: AlUla is positioning itself as the center of cinema for the MENA region, turning its dramatic desert landscapes, heritage sites and newly built studio infrastructure into jobs, tourism and long‑term economic opportunity.

In a wide‑ranging interview, Zaid Shaker, executive director of Film AlUla, and Philip J. Jones, chief tourism officer for the Royal Commission for AlUla, laid out an ambitious plan to train local talent, attract a diverse slate of productions and use film as a catalyst for year‑round tourism.

“We are building something that is both cultural and economic,” said Shaker. “Film AlUla is not just about hosting productions. It’s about creating an entire ecosystem where local people can come into sustained careers. We invested heavily in facilities and training because we want AlUla to be a place where filmmakers can find everything they need — technical skill, production infrastructure and a landscape that offers limitless variety. When a director sees a location and says, ‘I can shoot five different looks in 20 minutes,’ that changes the calculus for choosing a destination.”

At the core of the strategy are state‑of‑the‑art studios operated in partnership with the MBS Group, which comprises Manhattan Beach Studios — home to James Cameron’s “Avatar” sequels. “We have created the infrastructure to compete regionally and internationally,” said Jones. “Combine those studios with AlUla’s natural settings and you get a proposition that’s extremely attractive to producers; controlled environment and unmatched exterior vistas within a short drive. That versatility is a real selling point. We’re not a one‑note destination.”

The slate’s flagship project, the romantic comedy “Chasing Red,” was chosen deliberately to showcase that range. “After a number of war films and heavy dramas shot here, we wanted a rom‑com to demonstrate the breadth of what AlUla offers,” said Shaker. “‘Chasing Red’ uses both our studio resources and multiple on‑location settings. It’s a story that could have been shot anywhere — but by choosing AlUla we’re showing how a comical, intimate genre can also be elevated by our horizons, our textures, our light.

“This film is also our first under a broader slate contract — so it’s a proof point. If ‘Chasing Red’ succeeds, it opens the door for very different kinds of storytelling to come here.”

Training and workforce development are central pillars of the program. Film AlUla has engaged more than 180 young Saudis in training since the start of the year, with 50 already slated to join ongoing productions. “We’re building from the bottom up,” said Shaker. “We start with production assistant training because that’s often how careers begin. From there we provide camera, lighting, rigging and data-wrangling instruction, and we’ve even launched soft‑skill offerings like film appreciation— courses that teach critique, composition and the difference between art cinema and commercial cinema. That combination of technical and intellectual training changes behavior and opens up real career pathways.”

Jones emphasized the practical benefits of a trained local workforce. “One of the smartest strategies for attracting productions is cost efficiency,” he said. “If a production can hire local, trained production assistants and extras instead of flying in scores of entry‑level staff, that’s a major saving. It’s a competitive advantage. We’ve already seen results: AlUla hosted 85 productions this year, well above our initial target. That momentum is what we now aim to convert into long‑term growth.”

Gender inclusion has been a standout outcome. “Female participation in our training programs is north of 55 percent,” said Shaker. “That’s huge. It’s not only socially transformative, giving young Saudi women opportunities in an industry that’s historically male-dominated, but it’s also shaping the industry culture here. Women are showing up, learning, and stepping into roles on set.”

Looking to 2026, their targets are aggressive; convert the production pipeline into five to six feature films and exceed 100 total productions across film, commercials and other projects. “We want private-sector partners to invest in more sound stages so multiple productions can run concurrently,” said Jones. “That’s how you become a regional hub.”

The tourism case is both immediate and aspirational. “In the short term, productions bring crews who fill hotels, eat in restaurants and hire local tradespeople,” said Shaker. “In the long term, films act as postcards — cinematic invitations that make people want to experience a place in person.”

Jones echoed that vision: “A successful film industry here doesn’t just create jobs; it broadcasts AlUla’s beauty and builds global awareness. That multiplies the tourism impact.”

As “Chasing Red” moves into production, Shaker and Jones believe AlUla can move from an emerging production destination to the region’s filmmaking epicenter. “We’re planting seeds for a cultural sector that will bear economic fruit for decades,” said Shaker. “If we get the talent, the infrastructure and the stories right, the world will come to AlUla to film. And to visit.”