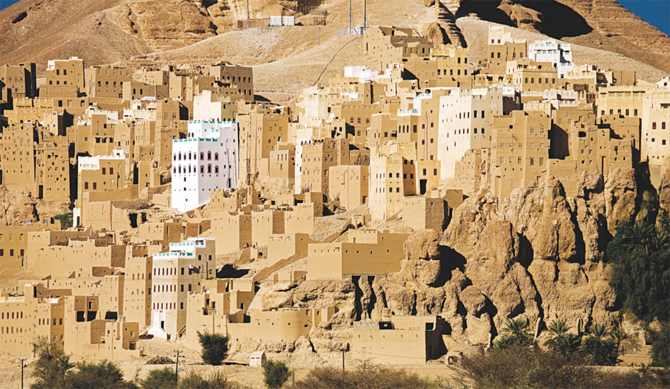

SINGAPORE: The first car to arrive in Tarim, a historic town in the Hadhramaut Valley of Yemen, was an American Studebaker.

It had traveled across oceans and continents to get there — but not without the help of one prominent Arab family in Singapore.

“Tarim’s first car was bought and imported to Singapore by the Alkaff family,” said Zahra Aljunied, whose forefathers came from Tarim. The 62-year-old senior librarian is a fifth-generation Singaporean Arab from the lineage of Syed Omar Aljunied, one of the first Arabs to set foot in the port in 1820.

“They disassembled the car, put it on a ship, and brought it to Mukallah, which is nine hours’ drive from Tarim,” she told Arab News. “Then it was put on the back of camels, brought all the way to Tarim, where they reassembled the car with the S (Singapore number) plate before it was driven.”

Though the Indian Ocean separates the Asian metropolis of Singapore and the Arabian deserts of Hadhramaut, the ties that bind them run deep and go back centuries.

Almost all Arabs in Southeast Asia trace their ancestry to Hadhramaut, a region on the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula in present-day Yemen. Referred to as Hadhrami Arabs, they began migrating to Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore in large numbers from the mid-18th century.

Names such as Aljunied, Alkaff and Alsagoff are familiar to most Singaporeans, as streets, buildings, mosques, schools and even a district have been named after these prominent Arab clans. Yet few realize the impact the early Muslim settlers had on colonial Singapore, or on the families they left behind in the homeland.

“When Sir Stamford Raffles founded Singapore in 1819, one of the first things he did was to persuade Hadhrami families to come here,” recounted Singapore’s former foreign minister George Yeo at the launch of a 2010 exhibition about Arabs in Southeast Asia.

“Syed Mohammed Harun Aljunied and (his nephew) Syed Omar Aljunied from Palembang (in present-day Indonesia) were given a warm welcome, and from that time on Singapore became the center of the Hadhrami network in Southeast Asia,” Yeo said.

Zahra Aljunied, a fifth-generation Singaporean Arab. (AN photo by Munshi Ahmed)

Attracted by Singapore’s free port status, the two men — already successful merchants in Palembang — brought everything they owned “lock, stock and barrel,” said Zahra, whose paternal grandmother came from the line of Syed Omar.

Syed Omar was born in 1792 in Tarim, a small town in South Yemen widely considered a theological, judicial and academic hub in Hadhramaut. The Malays saw him as a prince because the Aljunied family, being part of the Ba’alawi tribe, can trace their ancestry to the Prophet Muhammad and were regarded as legitimate custodians of Islam.

But growing up, Tarim was a place that Zahra and her siblings shunned.

“When we were kids, my grandmother or grandfather will say: ‘If you are naughty, we will send you back to Hadhramaut’,” she said, laughing. “So we looked at Hadhramaut as a place we didn’t want to be in. We didn’t look forward to going there.”

But her journey towards discovering her roots took a new turn in 2004, when she became part of a research team from Singapore organizing an exhibition entitled “Rihlah — Arabs in Southeast Asia.”

That journey drew her back to Hadhramaut five times, and also to Palembang and Java in Indonesia. She discovered that decades of Southeast Asian influence gave Hadhramaut a unique culture not found in other parts of the Middle East.

“When I first went to Hadhramaut, it was so different from Sanaa … It’s their way of life — what they eat, wear, even the language,” she said.

While men in Sanaa usually wear the traditional Yemeni dress called a thobe, men in Hadhramaut prefer shirts and sarongs, traditional Indonesian clothing often made of Javanese batik.

“Yes, they dress differently … They eat belacan (the shrimp paste condiment used in Southeast Asia) and keropok (Malay/Indonesian prawn crackers), all imported from Indonesia,” Zahra said.

“You ask me how I’ve assimilated to the culture here, but over in Tarim, they have already assimilated to the culture that is imported from here.”

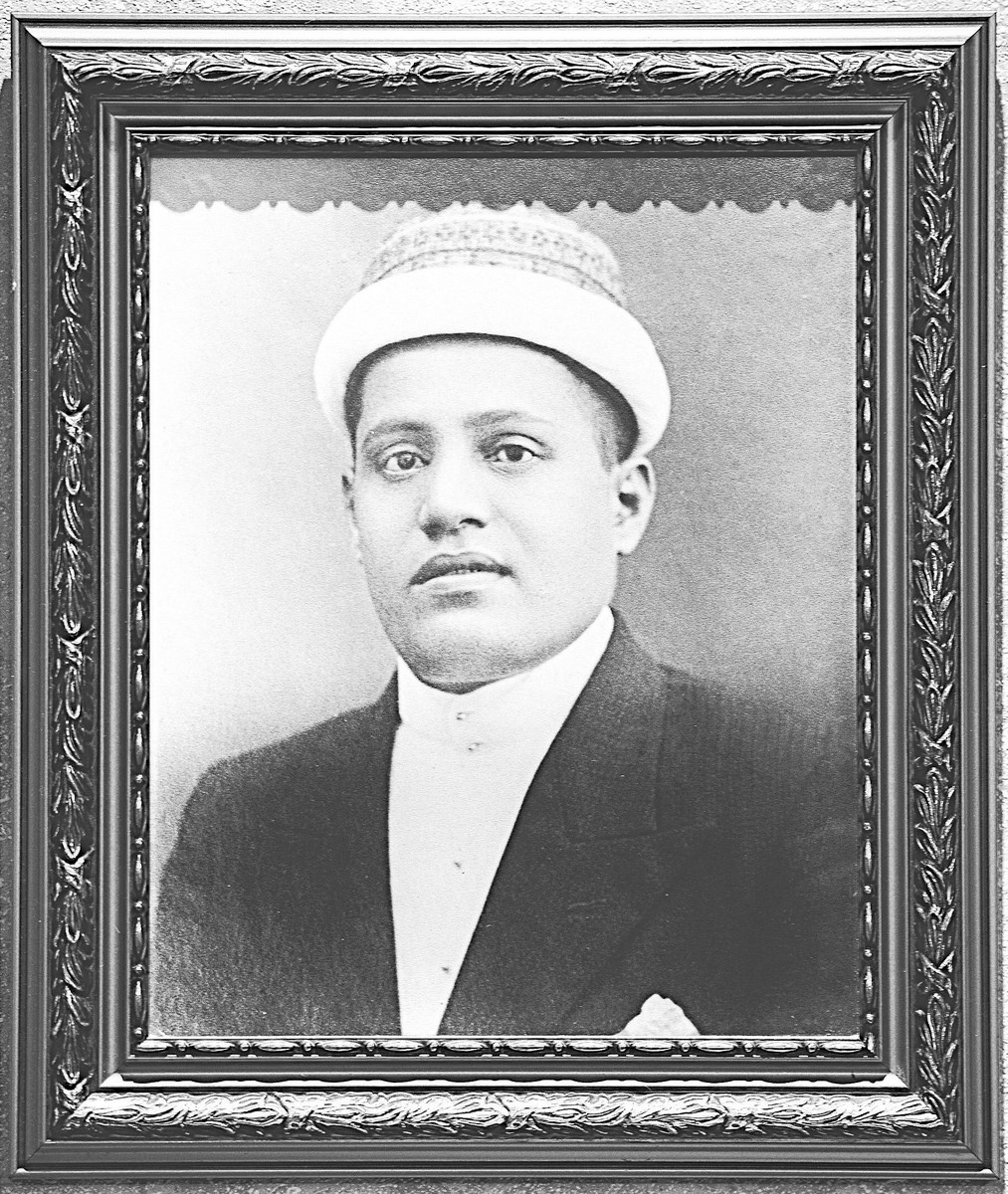

Abdul Rahman bin Junied Aljunied, Zahra’s great grandfather. (AN photo by Munshi Ahmed)

Hadhramis have been traversing the Indian Ocean for centuries, said Syed Farid Alatas, professor of sociology at the National University of Singapore.

Situated at the crossroads of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, Hadhramaut was at that time a key post on the ancient spice trade route.

“The migration to Southeast Asia was relatively recent compared with the other migrations in East Africa and southern India,” said Alatas, who is also from a prominent Hadhrami family in Southeast Asia.

Famine and economic hardship were some push factors, he added. “But I think you can’t divorce that from a certain interest that Hadhramis have because they were living in the coastal areas. Hadhramaut has a long coast and so they were seafaring and interested in going out, in exploring other places.”

However, the homeland was never far from their hearts. Parents used to send their young sons to Hadhramaut to study in religious schools, where they would to learn Arabic and Islamic values. Sometimes they also married off their local-born daughters to Hadhrami men.

“They want their sons to know Arabic, so they send them to study there for many years, like my father, my uncle, some of my brothers,” Zahra said. “My grandfather was the same like others before him. They often sent money and many things back to Hadhramaut. Maybe once in three months, my grandmother would get a big carton and put lots of things inside — keropok (prawn crackers), belacan (shrimp paste), the Three Rifles brand (a homegrown brand) men’s singlets.”

Remittances from the Far East soon became the most important source of income for those in the homeland as overpopulation, poverty and arid farming conditions made it difficult to sustain traditional livelihoods such as agriculture, herding and trade.

By the 19th century, Arabs in Southeast Asia dominated trade, commerce and maritime networks. They operated the largest fleets and vessels in the Indo-Malay archipelago, and the port of Singapore became the hub of Hadhrami shipping. For a time, Singapore was also the major transit point for Hajj pilgrims.

Hadhrami Arabs were instrumental in the spread of Islam in the region. Many held high positions in civic and religious affairs or took part in politics. Others owned large swathes of land in the early colonial days — an estimated 50 percent of Singapore’s total land mass at one time, according to one scholar.

Known for their philanthropy, they also donated much of their land for cemeteries, hospitals and places of worship including famous landmarks such as St. Andrew’s Cathedral and Singapore’s first mosque, Masjid Omar Kampong Melaka — both of which still stand today.

After World War II, however, Arab wealth and prominence in Singapore began to fade, due in part to rent controls as the government sought to curb inflation. The introduction of the 1966 land acquisition act also affected Arab land ownership as the post-independence government bought property for state development.

Estimates put the Arab population in Singapore at about 10,000 today, but some say that the numbers are difficult to determine as many have assimilated into the Malay community and no longer distinguish themselves as Arabs.

Syed Harun bin Hassan Aljunied, Zahra’s paternal grandfather. (AN photo by Munshi Ahmed)

“Many Hadhrami emigrants intermarried with their host societies and integrated so completely that after the passing of a generation or two, their descendants could no longer be regarded as members of a diaspora. Others, however, chose to retain their affiliation to the homeland,” wrote historian Ulrike Freitag in her book “Indian Ocean Migrants and State Formation in Hadhramaut: Reforming the Homeland.”

However, she warned that “it would be premature to conclude that members of the Hadhrami diaspora have either all departed or assimilated to the extent of renouncing their Hadhrami identity.”

Some observers say that Singaporean Arabs have lost their identity since many young Arabs no longer speak Arabic and have little ties to Hadhramaut, but Alatas disagreed.

“Have Singaporean Chinese lost their identity?” he asked. “Singaporean Chinese are not like the Chinese in China. Even if they speak Mandarin, they think differently from Chinese in China. On that basis, is it fair to say that Chinese in Singapore have lost their identity?”

Arabs are no exception, he said. “You have Arabs in Singapore who feel and strongly identify themselves as Arab. On the other hand, you have those who have assimilated into Malay society — they know they have Arab ancestry, but they feel Malay.

“Then you have Arabs who are in between, who are creole.”

The war in Yemen has taken a huge human and economic toll on the country and disrupted transport links. Even those hoping to maintain ties with their ancestral home find it hard to return.

Flights have become irregular and expensive, and reaching Tarim now involves a 10-hour bus journey from Salalah in Oman, Zahra said.

“My father also stopped going,” she said sadly. “I miss Tarim.”