OXFORD: Arriving at the University of Oxford to begin her studies, Mahdiyah Rahman suddenly felt anxious. “I didn’t know how many other Muslim students would be there. I wasn’t sure what to expect.”

During her first week, the 19-year-old student discovered that there were just two other Muslims in Oriel, the Oxford college where she would eat, sleep and study during her time at the university. “I was the only one there wearing a headscarf,” she recalled. Over the summer Rahman had given little thought to the realities of practicing her faith at university, but standing in the crowded hall at Freshers’ Fair, surrounded by hundreds of stalls advertising student clubs and societies, she felt overwhelmed.

Then a banner for the Oxford University Islamic Society (ISoc) caught her eye. “They make you feel like there’s a community that will look out for you while you’re here,” she said. “No one who has joined the ISoc ever wants to leave.”

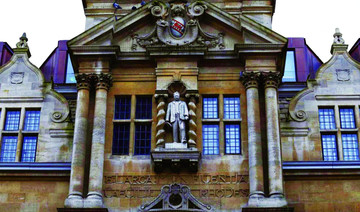

Muslim students starting out at Oxford University — an institution steeped in tradition where the earliest colleges date back to the 13th century — can struggle with a profound sense of alienation.

“A lot of the Muslims here are also ethnic minorities, so there is already this feeling that you’re going to be on the periphery,” Rahman told Arab News. Historically seen as the preserve of a white, upper-class elite, the student body has grown gradually more diverse, reflecting the changing character of modern, multicultural Britain in the country’s oldest seat of learning.

Faith societies such as ISoc allow students to engage with people who share their values and beliefs, and expand their network outside college life. Attending some activities during Freshers’ Week, as well as college parties and balls, can be difficult for Muslim students trying to avoid the alcohol-fueled atmosphere of university social life.

Getting halal meals in the college dining halls can also be a challenge, as Ayesha Musa, 19, the ISoc secretary, discovered when she arrived at Jesus College, Oxford to study medicine.

“That was a big adjustment — having to be vegetarian,” she said. “I wanted to eat with people in college and was reluctant to miss out on that social experience for the sake of getting something different to eat.”

But many Muslim students say they are “pleasantly surprised” by provisions made to accommodate their faith. “Overall I’ve been really impressed,” Musa said. Being part of ISoc means “you never miss an aspect of practicing your faith the way you would do at home with your family.”

Rahman was surprised by the size of university’s central prayer room, which “even has ablution facilities.”

Famously described as the “city of dreaming spires” — a reference by British poet Matthew Arnold to its scholarly atmosphere — Oxford, in southeast England, is one of the UK’s fastest-growing and most ethnically diverse cities.

Muslims account for 10,320 of the city’s population of 151,906, according to a 2011 census — up from 5,309 Muslim residents the previous decade. The findings also showed that a third of people living here were born abroad, contributing to the atmosphere of multiculturalism flourishing in the country’s oldest seat of learning.

“It’s very cosmopolitan. We live in one of the most beautiful and cohesive places in the country,” said Imam Monawar Hussein, who founded the Oxford Foundation to support disaffected young people and is also the Muslim tutor at Eton College, another of England’s renowned academic institutions.

In the university, this is reflected across the departments, where course names are beginning to reflect the demand for a wider educational experience in branches of Islamic studies.

The theology faculty, one of the oldest and most distinguished in the world, now offers a paper in Islam, while the Department of Economics has a professor specializing in the economics of Muslim societies.

“Oxford is possibly the most international university in the country and the preferred (higher learning) destination for many around the world,” said Farhan Nizami, founder director of the Oxford Center for Islamic Studies.

In recent years, he said, “the complexion of the Muslim student body has changed,” with most, he expects, now British citizens rather than overseas students.

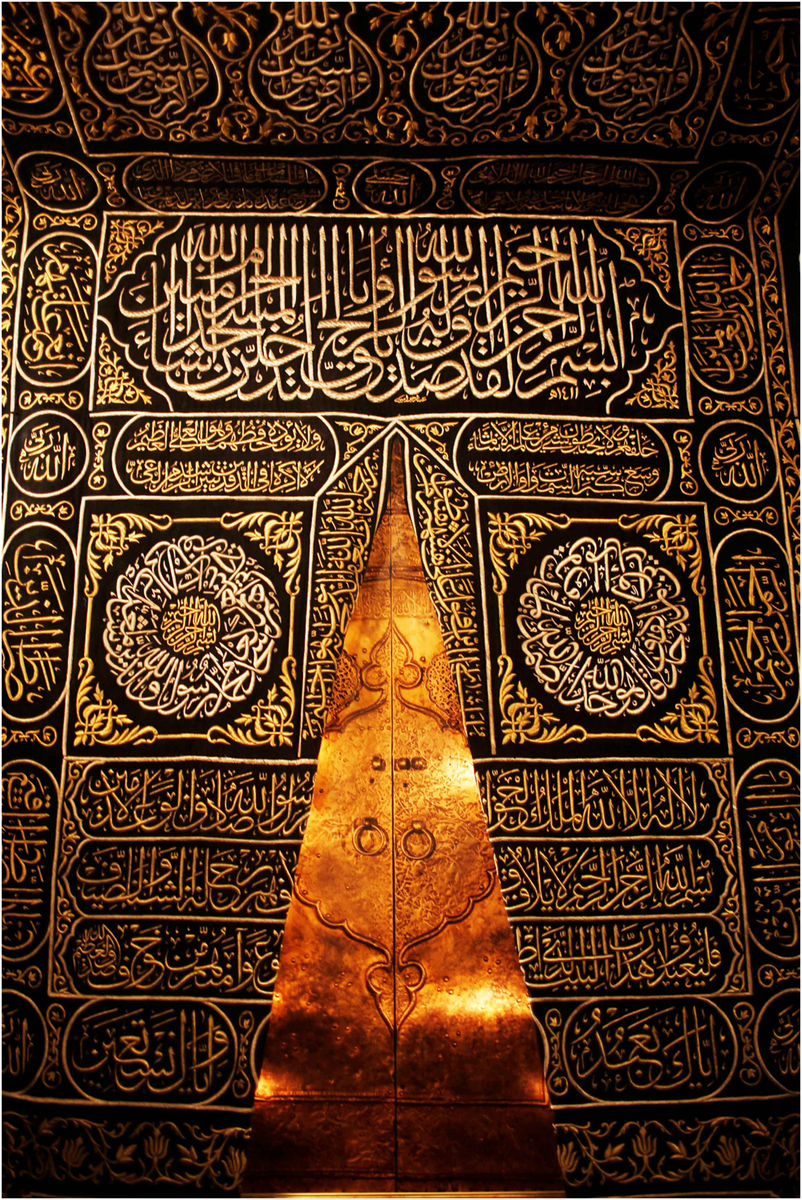

Woven with devotion: The curtain, known as “sitara”, forms the most elaborate part of the kiswa and covers the door of the Kaaba in Makka. Reuters

Set up in 1985 to promote the study of Islam and the Muslim world, the center has been instrumental in broadening the remit of oriental studies at the university to incorporate Muslim societies outside the Middle East and, increasingly, the study of Muslims in the West.

Last year the center, which is under the patronage of Prince Charles, opened the doors to an impressive new facility that rivals the traditional Oxford colleges for scale and grandeur.

With its domed roofs and columned cloisters opening on to the King Fahd quad — named after its Saudi benefactor — the building captures the lofty feel of its older neighbors with a design rooted in Islamic architecture.

“We wanted a building that would blend with Oxford and sit comfortably here,” said Nizami.

Inside the center’s white walls, which still have the gleam of fresh paint, different areas are named

after the countries that funded them, including the Malaysia Auditorium. Downstairs, polished bookshelves laden with volumes are tucked under the well-lit arches of the Kuwait Library, which is empty on the first day of the summer holidays.

A few professors eat lunch in the sunny Oman hall ahead of a guest lecture, part of a program of prestigious speakers that includes heads of state, members of the Arab League and royalty. From here, glass doors open out into tranquil gardens, where a satellite fountain runs between rose beds and down through an immaculate sloping lawn.

The mosque — a gift from the UAE — is one of four in Oxford, where for many decades Muslims had to make do with makeshift prayer halls, starting with the basement beneath an Indian restaurant in Jericho, which is one of the oldest quarters of the city.

Today, the eatery is a popular venue for university students, its faded facade now painted a smart powder-blue and the shabby neon sign replaced by elegant gold lettering.

Tables booked by groups from the university reflect the social, religious and ethnic diversity of Oxford social life, which groups such as ISoc actively promote. “I know in other universities the Islamic societies can be a bit polarizing and are sometimes inaccessible to non-Muslims,” but the ISoc, first-year student Rahman said, is open to all.

“I often bring my non-Muslim friends along to our events,” she said, adding that some envy her extended ISoc family. “They offer so much support. After exams I had messages from at least 20 ISoc girls congratulating me.”

King Fahd quad, named after its Saudi benefactor, at the Center. Reuters

During Ramadan, 80 to 90 students congregated every evening to pray together and break their fast. “I’m a bit sad it’s over, actually,” said Rahman, who found that the communal atmosphere made up for spending Ramadan away from home — a first for many students.

The society also hosts interfaith events as well as weekly socials and activities such as the Sisters’ Mocktails Party “to make sure Muslims don’t feel alone and can socialize with people who have the same values as them.”

“It is difficult and does require a thick skin,” Rahman said. But looking back on her first year, the experience of being a Muslim student in Oxford has been “overwhelmingly positive.” Now she is more daunted by the prospect of a whole summer away from college and her ISoc friends.