BEIRUT: Mona El-Hallak is standing in what was once Photo Mario, a neighborhood photographer’s studio located in Beit Beirut in the Lebanese capital’s Sodeco district. In front of her are 80 negatives displayed in a glass cabinet.

“This one is my favorite,” she says, pointing at a medium-format negative. “See the twirls, the capillary breaks, the yellows, the blues. It’s artistic, the way it has deteriorated.”

The 80 negatives on show are just a fraction of the 8,000 that El-Hallak discovered when she first entered the building in 1994.

“When I looked at the photographs for the first time they would look back at me,” she recalls. “And because they’re negatives, they had these white eyes. There were men and women, girls and boys, families, portraits of couples. They had different styles of dress, different hairstyles, and posed in different ways. It was life in all its variety.

“I particularly remember a photograph that looked a lot like one my uncle had taken, and I realized that you identify with photographs beyond whether you know the person or not. You identify with a pose or a family portrait similar to one your own family had taken.”

It was this realization that led to the creation of the Photo Mario Archive Project, an initiative that seeks to recapture memories, not only of the studio and the neighborhood, but of the wider city via the identification of the photographer’s subjects and the recording of their stories. So far only three people have been identified.

“People think that the only aim of this project is to find these people and to tell their stories,” says El-Hallak, an architect and activist. “This is, of course, one aspect, but so many people who don’t know anybody in the photographs still look at them and talk about the memories that they trigger. I want all these stories.”

El-Hallak is consumed by the idea of Beirut’s collective memory. Her belief is that the city is the sum total of its people and their stories, and that maps are human, not geographic. To her the negatives are individual time capsules, and photography a “technology of memory.” Even Beit Beirut, an architectural marvel originally designed in a neo-Ottoman style by Youssef Aftimos in 1924, is nothing without the tales of its inhabitants.

Formerly known as the Barakat building, Beit Beirut was once a grand and impressive residential block made of ochre-colored sandstone. It still has an undeniable allure, despite its infamy as a snipers’ nest during Lebanon’s protracted civil war. Partially destroyed and neglected in the years that followed, it largely owes its existence to El-Hallak, who campaigned tirelessly to stop the building from being demolished. It has now been transformed by the architect Youssef Haidar into a museum to the memory of the city, although it remains, for the most part, controversially closed and unused.

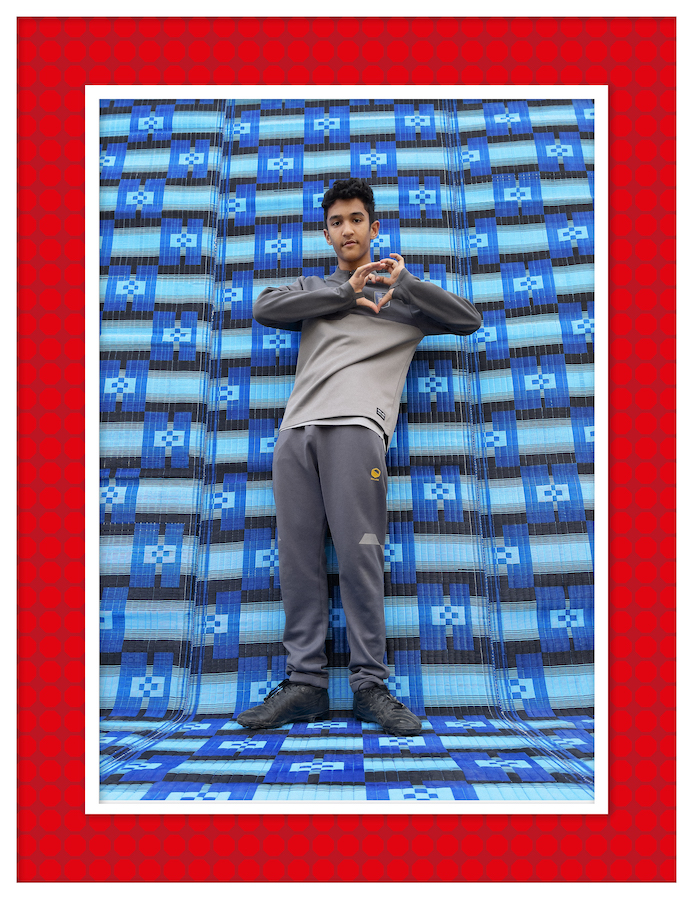

Photo Mario’s tiny studio was located on a mezzanine level just above the ground-floor commercial space and reached via a steep set of stairs. Less than two meters high, it had an array of curtain backdrops, some of which can be seen in the photographs that El-Hallak has developed with the help of the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC). The Arab Image Foundation assisted with the cleaning and restoration of the negatives.

Of those who have so far been identified, Dia El Turk was just two years old when his photograph was taken. In it, he sits in front of a wintery backdrop wearing a knitted outfit and lace-up ankle-boots. He was identified by his daughter Noura during AFAC’s 10th anniversary exhibition in Beit Beirut last November.

“It’s the only one we have left in the house,” says Noura, showing me a similar photograph of her father. It is almost identical, only portrait instead of landscape. “The outfit he’s wearing was knitted by my grandmother,” she adds with a smile.

“When I saw the picture it was like looking at my father’s past through my own eyes. I’m the one that lives in this country now, so it was such a beautiful parallel to see. It was very emotional. I hadn’t expected it to be.”

It is such emotion that El-Hallak hopes will drive her project forward. With thousands of negatives to be cleaned, restored and potentially developed, this is a long-term commitment. She even envisages a Photo Mario Cafeteria within Beit Beirut, with an additional digital platform allowing people to upload their photographs and stories. All, hopefully, will contribute to the permanent collection of the museum, creating a database of memory. “It’s like a constant exhibition of people’s portraits and a constant quest for identification,” she says.

The photographs — remnants of a bygone tradition of family portraiture — not only represent the past but are also a physical manifestation of Lebanese nostalgia; that idea of a pre-war golden age and the sometimes desperate attempts to salvage it. Uncropped, with distinctive black borders, they are intimate, peaceful, serene.

“Just looking at the picture it’s like 50 years passed by in front of my eyes,” says Dia from his home in Kuwait. “I can still remember the street, remember the smell of the street, how we used to go to the Sanayeh Garden to play, and how the streets were empty, with only a few cars.

“What I remember mostly from that time was a different environment. A different kind of culture. Everybody knew everybody. It was so beautiful and calm and green. Not like now. We knew everybody. Now you don’t know your neighbor.”

Dia’s photograph had been taken a few days before his family left Lebanon for Kuwait in 1965. Although they would return to Beirut for the summer every year, he wouldn’t move back to the country again until 1981, a year before the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. He would come and go for the next 15 years.

“Every time I left Lebanon I used to say goodbye to everyone as if I would never see them again,” says Dia, whose family was forced to move from Ras Al Nabaa to Hamra in 1987 due to the intensity of the fighting. “It broke my heart. Lebanon used to gather people, now it separates them. I think my story is like many Lebanese: My brother in Morocco, my sister in Cairo and my daughter in Lebanon.”

Haidar’s transformation of Beit Beirut — particularly the use of steel prosthetics and the demolition of a rear service staircase — has not been without its critics, El-Hallak among them. And a year-and-a-half after its completion, the building remains closed.

“For me, the Photo Mario project shows the municipality that this archive needs to be cleaned, restored and shown to the public,” says El-Hallak. “It’s kind of my first step to tell the municipality, ‘Do something about this building that makes the people appropriate it.’

“Every portrait has a story to tell that relates to life in the city before the war and reflects the socio-economic and demographic conditions of that time,” she continues. “This archive and the stories that it will bring back to Beit Beirut will reconstruct a part of our history.”