JERUSALEM: For Pierre Krahenbuhl, the commissioner general of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), it was a rare piece of good news during the biggest crisis in the history of his organization.

During the Arab League summit in the Saudi city of Dhahran, King Salman announced a $50 million contribution to help support the UN agency responsible for the care of Palestinian refugees. Within days the UAE had followed suit.

“I was deeply appreciative of the amount and that was made at such a senior level and I was pleased that there was close interaction with the leadership of the UAE who followed suit in making a similar amount of support within a week,” said Krahenbuhl, a Swiss national who was appointed by UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon in 2014.

The donations came after months of uncertainty about a gaping hole in the agency’s funding. On Jan. 16, Donald Trump announced that Washington would withhold $65 million out of the first tranche of the $125 million of contributions for 2018. The decision placed in doubt the provision of services such as health care and education to tens of thousands of Palestinians.

In a wide-ranging exclusive interview with Arab News, Krahenbuhl discussed UNRWA’s financial status, relations with the US, and the status of Palestine refugees in Gaza, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan.

Speaking from his humble East Jerusalem office, he said the US decision was a major disappointment to the UN agency.

“In past years, the US contributed an average of $350 million per year. They have always been a generous and stable partner to UNRWA.”

Last year Washington gave the UN agency $364 million. “My understanding is that in Congress the amount is still there, but that will require a political decision to get it released, and we don’t presently expect that to happen.”

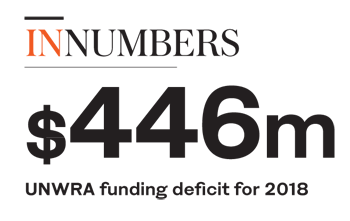

With a huge $446 million deficit in 2018, UNRWA went back to the international community that had given it a mandate to serve Palestinian refugees. An international emergency fundraising conference sponsored by Sweden, Jordan and Egypt was quickly convened in mid-March in Rome. More than 25 foreign ministers or deputy foreign ministers attended, as well as the UN Secretary General and the Palestinian prime minister.

“The message of this high-level attendees was important politically. Their presence reflected that UNRWA is an organization that needs to be protected,” said the commissioner general.

In the few months since the Trump announcement, UNRWA has managed to gather funds of more than $200 million. Of this, $100 million was raised at the conference held in Rome on March 15, as countries such as Qatar, Turkey, India, Norway and Canada made contributions. While the vast majority of the support so far has come from member states, Krahenbuhl is confident of being able to raise a lot more money from private individuals and national organizations.

Shortly after the announcement was made by Trump, UNRWA officials realized that they needed a campaign with a powerful message.

Shortly after the announcement was made by Trump, UNRWA officials realized that they needed a campaign with a powerful message.

“Many ideas where thrown around and it was energizing to see Palestine refugees, student parliaments, and our staff brainstorming to come up with a strong slogan.”

The consensus fell on a simple but powerful one: “Dignity is priceless.”

The campaign was launched within days of Trump’s announcement. “It is important to stress concepts such as dignity and rights. I know that no Palestinian refugee wants to trade food for a solution. No money can buy dignity and respect of their rights. The campaign has opened space for us.”

The UN agency that normally deals with member states all of a sudden was able to portray a strong concept that was very human.

“With the campaign people rediscovered another side of our mandate. For instance, in Indonesia people were surprised that we have 98 percent of our staff are Palestine refugees.”

The UN official added that UNRWA will make a powerful fundraising appeal during Ramadan. The agency has become eligible to receive Zakat funds and it

plans to engage with various nationalist institutions.

“I was in Turkey and met President Erdogan who committed to mobilize the national Turkish institutions. We are diversifying

well, both in terms of sources and ways of fundraising.”

Despite his efforts to raise money for the UN agency, Krahenbuhl said that the most challenging effect of years of wars and siege is felt on the emotional level — particularly in Gaza where years of Israeli siege have pushed the economic and humanitarian situation to a new low in recent months.

“The psychological effects are deep and devastating; our medical colleagues talk about an epidemic of psycho-social conditions in Gaza.”

Krahenhuhl explains that due to the blockade and conflict there is no hope on the horizon. “They go to school, but 65 percent will not get a job and 90 percent of our students have never left Gaza. We have 270,000 students studying in Gaza.”

The UN official is concerned about the long-term emotional effects on the population of Gaza.

“We give food to one million people, a population who are highly educated and who used to run their own businesses. They lost all that because of the blockade. I am proud we can help them.”

Between 250,000 and 350,000: The number of Palestinians expelled from their homes by Zionist paramilitaries between the passage of the UN partition plan in November 1947 and Israel’s declaration of independence on May 14, 1948.