DUBAI: Our pick of the most influential films from the Golden Age of Arab cinema will help you decide what classic movie you are going to watch this week. So grab your popcorn, turn off your phone and take your pick.

“Doa Al-Karawan”

(The Nightingale’s Prayer)

The prolific Henry Barakat directs this adaptation of acclaimed writer Taha Hussein’s 1934 novel. The compelling, claustrophobic tale follows illiterate housekeeper Amna (Faten Hamama) as she tries to get revenge on ‘The Engineer’ (Ahmad Mazhar) who has seduced her sister and ruined her reputation.

“Al-Ard”

(The Land)

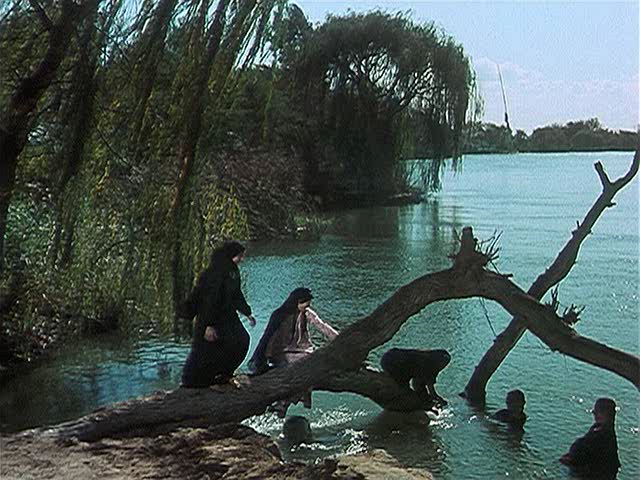

This 1969 adaptation of Abdel Rahman Al-Sharqawi’s novel, directed by Youseff Chahin, follows the struggle of a rural village in the 1930s against local authorities who are set to reduce its already meager water supply. A hard-hitting early examination of people-power that still resonates today.

“Nahr El-Hub”

(The River of Love)

Ezzel Dine Zulficar’s 1961 adaptation of “Anna Karenina” features the ‘First Couple’ of Egyptian cinema — Omar Sharif and Faten Hamama — in their last film together before their divorce. Hamama plays country girl Nawal, who is married off to a wealthy aristocrat but falls for army officer Khaled (Sharif). The couple’s real-life chemistry gives the movie an extra charge.

“Imm El-Arousa”

(Mother of the Bride)

Atef Salem’s 1964 comedy classic stars legendary Egyptian actors Tahiya Karioka and Emad Hamdi as Zeinab and Hussein — hardworking parents struggling to raise seven kids while arranging their eldest daughter’s upcoming wedding. And finding inventive ways to raise the necessary funds.

“Al-Mummia”

(The Mummy)

Ranked among Egyptian cinema’s greatest films, Shadi Abdel Salam’s 1969 movie is loosely based on the true story of the Abd El-Rasuls, a clan of grave robbers and black-market traders. It’s a thoughtful reflection on Egyptian identity which — like many on this list — hints at the tensions between rural and urban life.

“Khally Ballak Min ZouZou”

(Watch Out For ZouZou)

Starring Egyptian cinema icons Soad Hosny, Hussein Fahmy and Taheya Cariocca, Hassan Al Imam’s 1972 film — a perennial favorite in Egyptian households — tells the story of a college professor who falls in lust with a student. His fiancée decides to expose said student’s “shameful secret” — she was a dancer! — in an attempt to ruin her. Al Imam explored the friction between Egypt’s modernist urges and its conservative traditions.

The six most influential films from the Golden Age of Arab cinema

The six most influential films from the Golden Age of Arab cinema

- Celebrate the heyday of Arab cinema with these timeless classics

- From tragedies to comedies, these films are iconic and loved across the Arab world

From historic desert landscapes to sound stages: AlUla’s bid to become the region’s film capital

DUBAI: AlUla is positioning itself as the center of cinema for the MENA region, turning its dramatic desert landscapes, heritage sites and newly built studio infrastructure into jobs, tourism and long‑term economic opportunity.

In a wide‑ranging interview, Zaid Shaker, executive director of Film AlUla, and Philip J. Jones, chief tourism officer for the Royal Commission for AlUla, laid out an ambitious plan to train local talent, attract a diverse slate of productions and use film as a catalyst for year‑round tourism.

“We are building something that is both cultural and economic,” said Shaker. “Film AlUla is not just about hosting productions. It’s about creating an entire ecosystem where local people can come into sustained careers. We invested heavily in facilities and training because we want AlUla to be a place where filmmakers can find everything they need — technical skill, production infrastructure and a landscape that offers limitless variety. When a director sees a location and says, ‘I can shoot five different looks in 20 minutes,’ that changes the calculus for choosing a destination.”

At the core of the strategy are state‑of‑the‑art studios operated in partnership with the MBS Group, which comprises Manhattan Beach Studios — home to James Cameron’s “Avatar” sequels. “We have created the infrastructure to compete regionally and internationally,” said Jones. “Combine those studios with AlUla’s natural settings and you get a proposition that’s extremely attractive to producers; controlled environment and unmatched exterior vistas within a short drive. That versatility is a real selling point. We’re not a one‑note destination.”

The slate’s flagship project, the romantic comedy “Chasing Red,” was chosen deliberately to showcase that range. “After a number of war films and heavy dramas shot here, we wanted a rom‑com to demonstrate the breadth of what AlUla offers,” said Shaker. “‘Chasing Red’ uses both our studio resources and multiple on‑location settings. It’s a story that could have been shot anywhere — but by choosing AlUla we’re showing how a comical, intimate genre can also be elevated by our horizons, our textures, our light.

“This film is also our first under a broader slate contract — so it’s a proof point. If ‘Chasing Red’ succeeds, it opens the door for very different kinds of storytelling to come here.”

Training and workforce development are central pillars of the program. Film AlUla has engaged more than 180 young Saudis in training since the start of the year, with 50 already slated to join ongoing productions. “We’re building from the bottom up,” said Shaker. “We start with production assistant training because that’s often how careers begin. From there we provide camera, lighting, rigging and data-wrangling instruction, and we’ve even launched soft‑skill offerings like film appreciation— courses that teach critique, composition and the difference between art cinema and commercial cinema. That combination of technical and intellectual training changes behavior and opens up real career pathways.”

Jones emphasized the practical benefits of a trained local workforce. “One of the smartest strategies for attracting productions is cost efficiency,” he said. “If a production can hire local, trained production assistants and extras instead of flying in scores of entry‑level staff, that’s a major saving. It’s a competitive advantage. We’ve already seen results: AlUla hosted 85 productions this year, well above our initial target. That momentum is what we now aim to convert into long‑term growth.”

Gender inclusion has been a standout outcome. “Female participation in our training programs is north of 55 percent,” said Shaker. “That’s huge. It’s not only socially transformative, giving young Saudi women opportunities in an industry that’s historically male-dominated, but it’s also shaping the industry culture here. Women are showing up, learning, and stepping into roles on set.”

Looking to 2026, their targets are aggressive; convert the production pipeline into five to six feature films and exceed 100 total productions across film, commercials and other projects. “We want private-sector partners to invest in more sound stages so multiple productions can run concurrently,” said Jones. “That’s how you become a regional hub.”

The tourism case is both immediate and aspirational. “In the short term, productions bring crews who fill hotels, eat in restaurants and hire local tradespeople,” said Shaker. “In the long term, films act as postcards — cinematic invitations that make people want to experience a place in person.”

Jones echoed that vision: “A successful film industry here doesn’t just create jobs; it broadcasts AlUla’s beauty and builds global awareness. That multiplies the tourism impact.”

As “Chasing Red” moves into production, Shaker and Jones believe AlUla can move from an emerging production destination to the region’s filmmaking epicenter. “We’re planting seeds for a cultural sector that will bear economic fruit for decades,” said Shaker. “If we get the talent, the infrastructure and the stories right, the world will come to AlUla to film. And to visit.”