DUBAI: Our pick of the most influential films from the Golden Age of Arab cinema will help you decide what classic movie you are going to watch this week. So grab your popcorn, turn off your phone and take your pick.

“Doa Al-Karawan”

(The Nightingale’s Prayer)

The prolific Henry Barakat directs this adaptation of acclaimed writer Taha Hussein’s 1934 novel. The compelling, claustrophobic tale follows illiterate housekeeper Amna (Faten Hamama) as she tries to get revenge on ‘The Engineer’ (Ahmad Mazhar) who has seduced her sister and ruined her reputation.

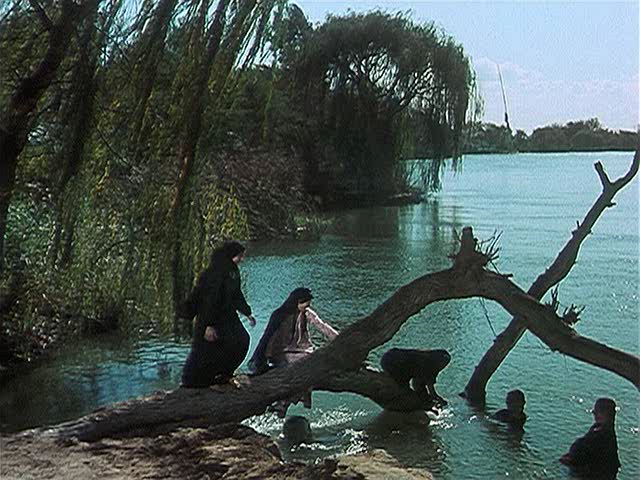

“Al-Ard”

(The Land)

This 1969 adaptation of Abdel Rahman Al-Sharqawi’s novel, directed by Youseff Chahin, follows the struggle of a rural village in the 1930s against local authorities who are set to reduce its already meager water supply. A hard-hitting early examination of people-power that still resonates today.

“Nahr El-Hub”

(The River of Love)

Ezzel Dine Zulficar’s 1961 adaptation of “Anna Karenina” features the ‘First Couple’ of Egyptian cinema — Omar Sharif and Faten Hamama — in their last film together before their divorce. Hamama plays country girl Nawal, who is married off to a wealthy aristocrat but falls for army officer Khaled (Sharif). The couple’s real-life chemistry gives the movie an extra charge.

“Imm El-Arousa”

(Mother of the Bride)

Atef Salem’s 1964 comedy classic stars legendary Egyptian actors Tahiya Karioka and Emad Hamdi as Zeinab and Hussein — hardworking parents struggling to raise seven kids while arranging their eldest daughter’s upcoming wedding. And finding inventive ways to raise the necessary funds.

“Al-Mummia”

(The Mummy)

Ranked among Egyptian cinema’s greatest films, Shadi Abdel Salam’s 1969 movie is loosely based on the true story of the Abd El-Rasuls, a clan of grave robbers and black-market traders. It’s a thoughtful reflection on Egyptian identity which — like many on this list — hints at the tensions between rural and urban life.

“Khally Ballak Min ZouZou”

(Watch Out For ZouZou)

Starring Egyptian cinema icons Soad Hosny, Hussein Fahmy and Taheya Cariocca, Hassan Al Imam’s 1972 film — a perennial favorite in Egyptian households — tells the story of a college professor who falls in lust with a student. His fiancée decides to expose said student’s “shameful secret” — she was a dancer! — in an attempt to ruin her. Al Imam explored the friction between Egypt’s modernist urges and its conservative traditions.

The six most influential films from the Golden Age of Arab cinema

The six most influential films from the Golden Age of Arab cinema

- Celebrate the heyday of Arab cinema with these timeless classics

- From tragedies to comedies, these films are iconic and loved across the Arab world

How science is reshaping early years education

DUBAI: As early years education comes under renewed scrutiny worldwide, one UAE-based provider is making the case that nurseries must align more closely with science.

Blossom Nursery & Preschool, which operates 32 locations across the UAE, is championing a science-backed model designed to close what it sees as a long-standing gap between research and classroom practice.

“For decades, early years education has been undervalued globally — even though science shows the first five years are the most critical for brain development,” said Lama Bechara-Jakins, CEO for the Middle East at Babilou Family and a founding figure behind Blossom’s regional growth, in an interview with Arab News.

She explained that the Sustainable Education Approach was created to address “a fundamental gap between what we know from science and what actually happens in nurseries.”

Developed by Babilou Family, the approach draws on independent analysis of research in neuroscience, epigenetics, and cognitive and social sciences, alongside established educational philosophies and feedback from educators and families across 10 countries. The result is a framework built around six pillars; emotional and physical security, natural curiosity, nature-based learning, inclusion, child rhythms, and partnering with parents.

Two research insights, Bechara-Jakins says, were particularly transformative. “Neuroscience shows that young children cannot learn until they feel safe,” she said, adding that stress and inconsistent caregiving can “literally alter the architecture of the developing brain.”

Equally significant was evidence around child rhythms, which confirmed that “pushing children academically too early is not just unhelpful — it can be counterproductive.”

Feedback from families and educators reinforced these findings. Across regions, common concerns emerged around pressure on young children, limited outdoor time and weak emotional connections in classrooms. What surprised her most was that “parents all sensed that something was missing, even if they couldn’t articulate the science behind it.”

At classroom level, the strongest body of evidence centres on secure relationships. Research shows that “secure attachments drive healthy brain development” and that children learn through trusted adults. At Blossom, this translates into practices such as assigning each child “one primary educator,” prioritising calm environments, and viewing behaviour through “a neuroscience lens — as stress signals, not misbehaviour.”

Bechara-Jakins believes curiosity and nature remain overlooked in many early years settings, despite strong evidence that both accelerate learning and reduce stress. In urban centres such as Dubai, she argues, nature-based learning is “not a luxury. It is a developmental need.”

For Blossom, this means daily outdoor time, natural materials, gardening, and sensory play — intentional choices aimed at giving children what science says they need to thrive.