CAIRO: Egypt’s chief prosecutor has claimed “forces of evil” are working inside the media to maliciously hurt the national interest as the country gears up for its presidential election.

Nabil Sadeq reminded his staff on Wednesday to monitor journalists’ work and initiate legal action against any news outlets deemed to be a threat to security — the latest sign the government is exerting growing pressure on political rivals and opposition activists.

A statement issued by the prosecutor’s office warned that “the forces of evil” — a favorite phrase of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi — are seeking “to undermine the security and safety of the nation through the broadcast and publication of lies and false news.”

His remarks came amid an escalating row with the BBC over an investigative report by the UK-based broadcaster examining the political situation in Egypt in the build-up to the March 26-28 election.

Entitled “Crushing Dissent in Egypt,” the documentary, which aired on Saturday, said torture is “routine nationwide” and featured interviews with several dissidents, including one who claimed to have been held without trial for more than two years and electrocuted while in government custody. “Anyone opposing the regime is at risk,” the documentary said.

These allegations have provoked a furious backlash from officials and government supporters in the Egyptian press. The State Information Service, which accredits and monitors foreign media, said the 23-minute program was “flagrantly fraught with lies” and violated “internationally recognized professional norms.”

In an attempt to rebut the BBC’s claims that the government has turned forced disappearances into “a trademark of the El-Sisi era,” one television channel invited a 23-year-old student whose case featured in the documentary on to a talk show. In her appearance, the student said she had not been detained by masked police but had run away from her mother, married and had a child.

The BBC has told Reuters it stands by the “integrity of our reporting teams.”

The journalist behind the documentary, Orla Guerin, has had an illustrious career, working in Europe, Africa and the Middle East. She received an honorary MBE in 2005 for her “outstanding service to broadcasting.”

Egypt’s presidential campaign began on Saturday, with the incumbent El-Sisi running against Mousa Mustafa Mousa, a relative unknown on the political scene.

El-Sisi came to power in 2013, ousting the democratically elected president and Muslim Brotherhood member Mohammed Mursi in a military coup after widespread public protests against his rule. He was subsequently elected in 2014, winning almost 97 percent of the vote, and is the overwhelming favorite to win another four-year term this time.

The government has arrested several of El-Sisi’s political rivals in recent weeks, including Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, founder of the Strong Egypt Party. He was accused of having ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, placed on a terrorist watch list and had his assets frozen after giving media interviews critical of the government during a trip to the UK.

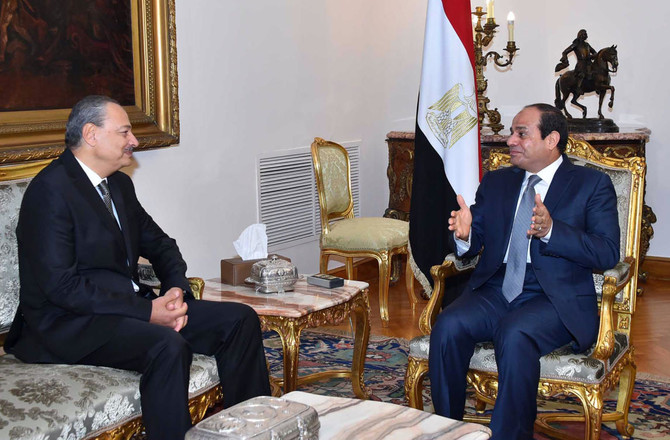

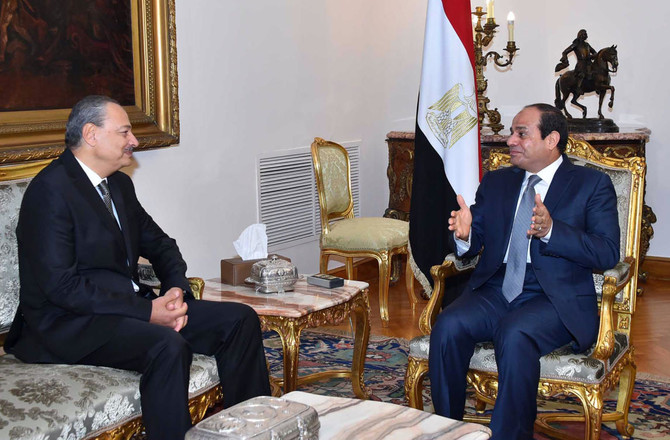

Egypt's chief prosecutor wants close monitoring of the media

Egypt's chief prosecutor wants close monitoring of the media

A ceasefire holds in Syria but civilians live with fear and resentment

QAMISHLI: Fighting this month between Syria’s government and Kurdish-led forces left civilians on either side of the frontline fearing for their future or harboring resentment as the country’s new leaders push forward with transition after years of civil war.

The fighting ended with government forces capturing most of the territory previously held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in the country’s northeast, and a fragile ceasefire is holding. SDF fighters will be absorbed into Syria’s army and police, ending months of disputes.

The Arab-majority population in the areas that changed hands, Raqqa and Deir Ezzor, have celebrated the SDF’s withdrawal after largely resenting its rule.

But thousands of Kurdish residents of those areas fled, and non-Kurdish residents remain in Kurdish-majority enclaves still controlled by the SDF. The International Organization for Migration has registered more than 173,000 people displaced.

Fleeing again and again

Subhi Hannan is among them, sleeping in a chilly schoolroom in the SDF-controlled city of Qamishli with his wife, three children and his mother after fleeing Raqqa.

The family is familiar with displacement after the years of civil war under former President Bashar Assad. They were first displaced from their hometown of Afrin in 2018, in an offensive by Turkish-backed rebels. Five years later, Hannan stepped on a land mine and lost his legs.

During the insurgent offensive that ousted Assad in December 2024, the family fled again, landing in Raqqa.

In the family’s latest flight this month, Hannan said their convoy was stopped by government fighters, who arrested most of their escort of SDF fighters and killed one. Hannan said fighters also took his money and cell phone and confiscated the car the family was riding in.

“I’m 42 years old and I’ve never seen something like this,” Hannan said. “I have two amputated legs, and they were hitting me.”

Now, he said, “I just want security and stability, whether it’s here or somewhere else.”

The father of another family in the convoy, Khalil Ebo, confirmed the confrontation and thefts by government forces, and said two of his sons were wounded in the crossfire.

Syria’s defense ministry in a statement acknowledged “a number of violations of established laws and disciplinary regulations” by its forces during this month’s offensive and said it is taking legal action against perpetrators.

A change from previous violence

The level of reported violence against civilians in the clashes between government and SDF fighters has been far lower than in fighting last year on Syria’s coast and in the southern province of Sweida. Hundreds of civilians from the Alawite and Druze religious minorities were killed in revenge attacks, many of them carried out by government-affiliated fighters.

This time, government forces opened “humanitarian corridors” in several areas for Kurdish and other civilians to flee. Areas captured by government forces, meanwhile, were largely Arab-majority with populations that welcomed their advance.

One term of the ceasefire says government forces should not enter Kurdish-majority cities and towns. But residents of Kurdish enclaves remain fearful.

The city of Kobani, surrounded by government-controlled territory, has been effectively besieged, with residents reporting cuts to electricity and water and shortages of essential supplies. A UN aid convoy entered the enclave for the first time Sunday.

On the streets of SDF-controlled Qamishli, armed civilians volunteered for overnight patrols to watch for any attack.

“We left and closed our businesses to defend our people and city,” said one volunteer, Suheil Ali. “Because we saw what happened in the coast and in Sweida and we don’t want that to be repeated here.”

Resentment remains

On the other side of the frontline in Raqqa, dozens of Arab families waited outside Al-Aqtan prison and the local courthouse over the weekend to see if loved ones would be released after SDF fighters evacuated the facilities.

Many residents of the region believe Arabs were unfairly targeted by the SDF and often imprisoned on trumped-up charges.

At least 126 boys under the age of 18 were released from the prison Saturday after government forces took it over.

Issa Mayouf from the village of Al-Hamrat, was waiting with his wife outside the courthouse Sunday for word about their 18-year-old son, who was arrested four months ago. Mayouf said he was accused of supporting a terrorist organization after SDF forces found Islamic chants as well as images on his phone mocking SDF commander Mazloum Abdi.

“SDF was a failure as a government,” Mayouf said “And there were no services. Look at the streets, the infrastructure, the education. It was all zero.”

Northeast Syria has oil and gas reserves and some of the country’s most fertile agricultural land. The SDF “had all the wealth of the country and they did nothing with it for the country,” Mayouf said.

Mona Yacoubian, director of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said Kurdish civilians in besieged areas are terrified of “an onslaught and even atrocities” by government forces or allied groups.

But Arabs living in formerly SDF-controlled areas “also harbor deep fears and resentment toward the Kurds based on accusations of discrimination, intimidation, forced recruitment and even torture while imprisoned,” she said.

“The experience of both sides underscores the deep distrust and resentment across Syria’s diverse society that threatens to derail the country’s transition,” Yacoubian said.

She added it’s now on the government of interim Syrian President Ahmad Al-Sharaa to strike a balance between demonstrating its power and creating space for the country’s anxious minorities to have a say in their destiny.

The fighting ended with government forces capturing most of the territory previously held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in the country’s northeast, and a fragile ceasefire is holding. SDF fighters will be absorbed into Syria’s army and police, ending months of disputes.

The Arab-majority population in the areas that changed hands, Raqqa and Deir Ezzor, have celebrated the SDF’s withdrawal after largely resenting its rule.

But thousands of Kurdish residents of those areas fled, and non-Kurdish residents remain in Kurdish-majority enclaves still controlled by the SDF. The International Organization for Migration has registered more than 173,000 people displaced.

Fleeing again and again

Subhi Hannan is among them, sleeping in a chilly schoolroom in the SDF-controlled city of Qamishli with his wife, three children and his mother after fleeing Raqqa.

The family is familiar with displacement after the years of civil war under former President Bashar Assad. They were first displaced from their hometown of Afrin in 2018, in an offensive by Turkish-backed rebels. Five years later, Hannan stepped on a land mine and lost his legs.

During the insurgent offensive that ousted Assad in December 2024, the family fled again, landing in Raqqa.

In the family’s latest flight this month, Hannan said their convoy was stopped by government fighters, who arrested most of their escort of SDF fighters and killed one. Hannan said fighters also took his money and cell phone and confiscated the car the family was riding in.

“I’m 42 years old and I’ve never seen something like this,” Hannan said. “I have two amputated legs, and they were hitting me.”

Now, he said, “I just want security and stability, whether it’s here or somewhere else.”

The father of another family in the convoy, Khalil Ebo, confirmed the confrontation and thefts by government forces, and said two of his sons were wounded in the crossfire.

Syria’s defense ministry in a statement acknowledged “a number of violations of established laws and disciplinary regulations” by its forces during this month’s offensive and said it is taking legal action against perpetrators.

A change from previous violence

The level of reported violence against civilians in the clashes between government and SDF fighters has been far lower than in fighting last year on Syria’s coast and in the southern province of Sweida. Hundreds of civilians from the Alawite and Druze religious minorities were killed in revenge attacks, many of them carried out by government-affiliated fighters.

This time, government forces opened “humanitarian corridors” in several areas for Kurdish and other civilians to flee. Areas captured by government forces, meanwhile, were largely Arab-majority with populations that welcomed their advance.

One term of the ceasefire says government forces should not enter Kurdish-majority cities and towns. But residents of Kurdish enclaves remain fearful.

The city of Kobani, surrounded by government-controlled territory, has been effectively besieged, with residents reporting cuts to electricity and water and shortages of essential supplies. A UN aid convoy entered the enclave for the first time Sunday.

On the streets of SDF-controlled Qamishli, armed civilians volunteered for overnight patrols to watch for any attack.

“We left and closed our businesses to defend our people and city,” said one volunteer, Suheil Ali. “Because we saw what happened in the coast and in Sweida and we don’t want that to be repeated here.”

Resentment remains

On the other side of the frontline in Raqqa, dozens of Arab families waited outside Al-Aqtan prison and the local courthouse over the weekend to see if loved ones would be released after SDF fighters evacuated the facilities.

Many residents of the region believe Arabs were unfairly targeted by the SDF and often imprisoned on trumped-up charges.

At least 126 boys under the age of 18 were released from the prison Saturday after government forces took it over.

Issa Mayouf from the village of Al-Hamrat, was waiting with his wife outside the courthouse Sunday for word about their 18-year-old son, who was arrested four months ago. Mayouf said he was accused of supporting a terrorist organization after SDF forces found Islamic chants as well as images on his phone mocking SDF commander Mazloum Abdi.

“SDF was a failure as a government,” Mayouf said “And there were no services. Look at the streets, the infrastructure, the education. It was all zero.”

Northeast Syria has oil and gas reserves and some of the country’s most fertile agricultural land. The SDF “had all the wealth of the country and they did nothing with it for the country,” Mayouf said.

Mona Yacoubian, director of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said Kurdish civilians in besieged areas are terrified of “an onslaught and even atrocities” by government forces or allied groups.

But Arabs living in formerly SDF-controlled areas “also harbor deep fears and resentment toward the Kurds based on accusations of discrimination, intimidation, forced recruitment and even torture while imprisoned,” she said.

“The experience of both sides underscores the deep distrust and resentment across Syria’s diverse society that threatens to derail the country’s transition,” Yacoubian said.

She added it’s now on the government of interim Syrian President Ahmad Al-Sharaa to strike a balance between demonstrating its power and creating space for the country’s anxious minorities to have a say in their destiny.

© 2026 SAUDI RESEARCH & PUBLISHING COMPANY, All Rights Reserved And subject to Terms of Use Agreement.