BEIRUT: Cars zoom by at speeds that do not seem possible. Mopeds carrying three or more people pop out from all directions.

Potholes scattered across the street force you to swerve left and right at any given moment, while unavoidable bumps dent the bottom of your vehicle causing you to bounce out of your seat.

Suddenly, daredevil pedestrians cross the road out of the blue as your car narrowly avoids hitting them.

This is not a scene from Mad Max or The Fast and the Furious franchise, this is a typical day of driving in Beirut.

“’If you can drive in Lebanon, you can drive anywhere,”’ my father proudly tells people who visit Beirut. Indeed, driving in Lebanon is an incredible test of both skill and patience.

When you get behind the wheel in Beirut you enter into an involuntary war and race with every other driver.

It shapes you, gives you courage, and teaches you to stand up for yourself. In a country where the rules of the road are largely ignored, each driver must fend for themselves.

Lebanon’s appalling driving habits are linked to the country’s chaotic history and ongoing political problems.

“’People here drive the way they do because of the war and chaos,”’ a high-ranking official in the Lebanese internal security forces told Arab News. “’The same people who lived through the 1975 war are still driving.”’

At that time, “’the driving test had lost its credibility and seriousness, causing a lot of unfit and unprofessional drivers to be on the road.”’

That approach has been passed down to the next generation of drivers.

It is common in Lebanon for parents to gift their children a driver’s license for their 18th birthday, without them actually taking the test. Parents bribe driving examiners and officials to get the paperwork.

This allows someone with no proper driver lessons to take control of a 1,500kg machine among thousands of others on dangerous roads. The practice not only endangers the inexperienced driver but those around them.

“’The fault firstly lies with the government for not taking it seriously, they are letting people go drive (without taking the test),”’ Kunhadi, Fady Jubran, president of the Road Safety NGO, told Arab News.

“’Then the fault comes on the parents … you don’t use the mobile in front of your children or speed in front of your children,”’ he added.

Lebanese motorist Houssam Rifai, 23, believes that people in the country are only focussed on getting from point A to point B in the fastest way possible, even if it meant passing through a few red lights here and there.

“’You lose hope that we will ever become civilized people who follow the rules … it’s madness,”’ Rifai, a civil engineer, told Arab News.

Interior Minister Nohad Al-Machnouk said on Tuesday that Lebanon needed to develop a proper public transportation system before improving the road network.

He told a local news channel that there was no solution to the traffic crisis since the nature of the streets make it difficult to have organized driving.

Lebanon once had a railroad system across the country, but this was halted during the civil war and much of the metal tracks were removed and sold.

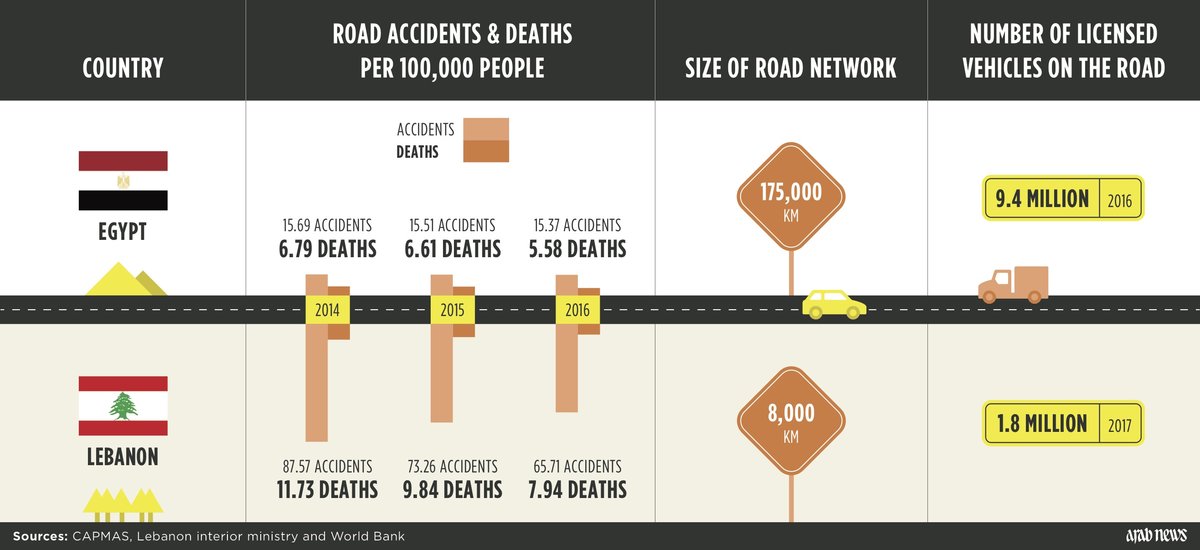

With few other options, most Lebanese are forced to use private cars to get from one place to the other, causing high levels of congestion. In a country with only 8,000km of road networks, there are currently 1.8 million cars for a population of 5 million.

And this means that Lebanon’s accident and road death rates are high for its relatively small population. Lebanon suffered about 4,000 road accidents in 2016 and almost 500 deaths, according to Interior Ministry figures.

“’In (some) European countries only 20 percent of the people use their cars and 80 percent use public transportation, while we are the opposite,”’ the security source said.

This makes it difficult for traffic officers to control and monitor the roads for violations, according to the officer. The absence of technology and smart cameras also plays a role. Outside of Beirut there is still a lack of traffic lights in many busy towns and cities.

There have been some signs of progress to tackle Lebanon’s appalling accident and death rates on the road.

Newly-placed radars have helped decrease speeding and the implementation of stricter and more expensive fines have decreased the number of road accidents and deaths by 22 percent over two years, the security source said.

But Lebanon still has a long way to go if it wants to shed its reputation as one of the world’s scariest places to travel by car.