UKHIA, BANGLADESH: The lost Rohingya boy made the journey from Myanmar alone, following strangers from other villages across rivers and jungle until they reached Bangladesh, where he had no family and no idea where to go.

“Some women in the group asked, ‘Where are your parents?’ I said I didn’t know where they were,” said Abdul Aziz, a 10-year-old whose name has been changed to protect his identity.

“A woman said, ‘We’ll look after you like our own child, come along’. After that I went with them.”

More than 1,100 Rohingya children fleeing violence in western Myanmar have arrived alone in Bangladesh since August 25, according to the latest UNICEF figures.

These solo children are at risk of sexual abuse, human trafficking and psychological trauma, the UN children’s agency said.

Many have seen family members brutally killed in village massacres in Rakhine state, where the Myanmar army and Buddhist mobs have been accused of crimes described by the UN rights chief as “ethnic cleansing.”

Others narrowly escaped with their own lives — some children arriving in Bangladesh bear shrapnel and bullet wounds.

The number of children who crossed into Bangladesh alone, or were split up from family along the way is expected to climb as more cases are discovered.

More than half of the 370,000 Rohingya Muslims who have made it to Bangladesh since August 25 are minors, according to UN estimates.

A sample of 128,000 new arrivals conducted in early September across five different camps, found 60 percent were children, including 12,000 under one year of age.

This presents a needle in a haystack scenario for child protection officers trying to find unaccompanied minors in sprawling refugee camps, where toddlers roam naked, children sleep outdoors and infants play alone in filthy water.

“This is a big concern. These children need extra support and help being reunited with family members,” Save the Children’s humanitarian expert George Graham said in a statement.

“At first they don’t talk, don’t eat, don’t play. They just sit still, staring a lot,” Moazzem Hossain, a project manager with Bangladeshi charity BRAC told AFP at a ‘child-friendly space’ run in partnership with UNICEF at Kutupalong refugee camp.

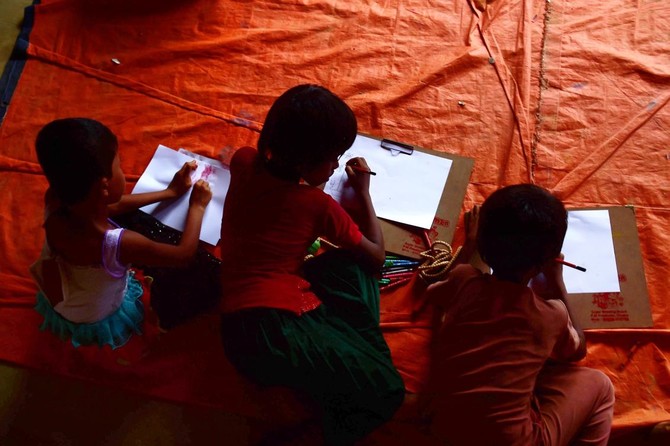

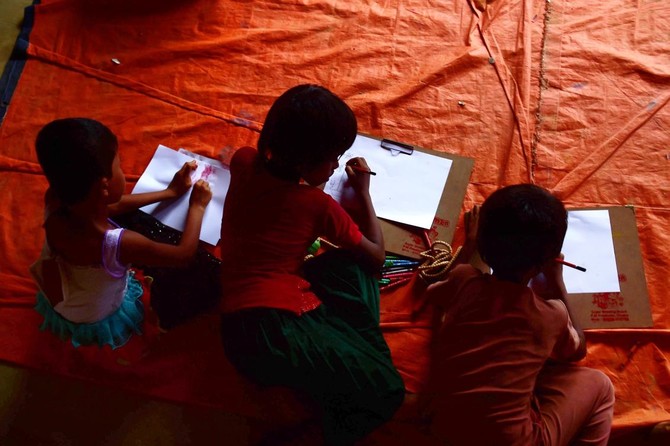

There are 41 of these safe zones across Bangladesh’s ever-expanding network of refugee camps.

Every day children, some carrying younger siblings, flock to the simple wooden huts for activities like singing, playing with toys and blocks and skipping ropes.

It is a welcome distraction from the misery outside, where monsoon rain turns the camp into a quagmire and exhausted refugees compete for dwindling food and space.

But playtime also allows staff to register details about a child’s background, monitor newcomers and keep an eye out for the tell-tale signs of a child on their own.

One such youngster was 12-year-old Mohammad Ramiz, who found himself alone after fleeing his village and tagged along with a group of adults.

“There was a lot of violence going on, so I crossed the river with others,” said Ramiz, not his real name.

“I ate leaves from the tree, and drank water to survive.”

There are fears the vulnerable minors could be exploited if left unsupervised in the camps, UNICEF Geneva spokesman Christophe Boulierac told AFP.

Girls are particularly at risk of being lured into child marriages, or trafficked to red-light districts in big cities where they are forced into prostitution and abused, he added.

But the facilities for refugee children are vastly overstretched.

Over just two days, 2,000 children came through a single ‘safe space’ in Kutupalong, little larger than a classroom with just a few staff on hand.

Thirty-five unaccompanied minors were identified over that period, Boulierac said, but more resources were needed to ensure others did not slip through the cracks.

“The faster we act, the more chance we have of finding their family,” he told AFP.

“The most important thing is to protect them because unaccompanied children, separated children, are particularly vulnerable and in danger.”

Hundreds of Rohingya children arrive in Bangladesh alone

Hundreds of Rohingya children arrive in Bangladesh alone

French hard-left party says evacuates Paris HQ after ‘bomb threat’

- The party’s coordinator Manuel Bompard said all employees and activists are safe

PARIS: France’s hard-left France Unbowed party said Wednesday it had to evacuate its Paris headquarters following a “bomb threat,” after it was accused of partial responsibility in the killing of a far-right activist.

“The national headquarters of LFI have just been evacuated following a bomb threat. Police services are on site. All employees and activists are safe,” the party’s coordinator Manuel Bompard said on X.

© 2026 SAUDI RESEARCH & PUBLISHING COMPANY, All Rights Reserved And subject to Terms of Use Agreement.