YANGON, Myanmar: Rohingya Muslims are once more fleeing in droves into Bangladesh, trying to escape the latest surge in violence in Rakhine state between a shadowy militant group and Myanmar’s military.

It is the newest chapter in the grim recent history of the Rohingya, a people of about one million reviled in Myanmar as illegal immigrants and denied citizenship.

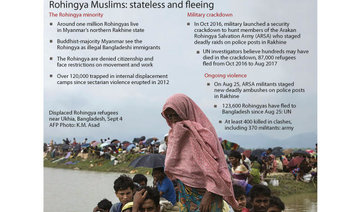

This is a fact box on them:

The Rohingya are the world’s largest stateless community and of one of its most persecuted minorities.

Using a dialect similar to that spoken in Chittagong in southeast Bangladesh, the Sunni Muslims are loathed by many in majority-Buddhist Myanmar who see them as illegal immigrants and call them “Bengali” — even though many have lived in Myanmar for generations.

They are not officially recognized as an ethnic group, partly due to a 1982 law stipulating that minorities must prove they lived in Myanmar prior to 1823 — before the first Anglo-Burmese war — to obtain nationality.

Most live in the impoverished western state of Rakhine but are denied citizenship and harassed by restrictions on movement and work.

More than half a million also live in Bangladeshi camps, although Dhaka only recognizes a small portion as refugees.

Sectarian violence between the Rohingya and local Buddhist communities broke out in 2012, leaving more than 100 dead and the state segregated along religious lines.

More than 120,000 Rohingya fled over the following five years to Bangladesh and Southeast Asia, often braving perilous sea journeys controlled by brutal trafficking gangs.

Then last October things got much worse.

Despite decades of persecution, the Rohingya largely eschewed violence.

But in October a small and previously unknown militant group — the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) — staged a series of well coordinated and deadly attacks on security forces.

Myanmar’s military responded with a massive security crackdown that UN investigators said unleashed “devastating cruelty” on the Rohingya that may amount to ethnic cleansing.

More than 250,000 new refugees have since flooded into Bangladesh bringing with them harrowing stories of murder, rape and burned villages.

A majority of those arrivals — 164,000 — have come in the past 12 days in the aftermath of a new series of ARSA ambushes and a subsequent Myanmar army crackdown.

Some 27,000 ethnic Rakhine Buddhists have also fled in the opposite direction saying Rohingya militants have murdered members of their community.

De facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi has faced widespread criticism for her stance on the Rohingya.

Her administration has dismissed concerns about rights abuses and refused to grant visas to UN officials tasked with investigating such allegations.

On Wednesday she said sympathy for the Rohingya was being generated by a “huge iceberg of misinformation.”

Analysts say Suu Kyi is hampered by the politically incendiary nature of the issue in Myanmar and the fact she has little control over the military.

Hatred toward the Rohingya is profound, particularly among Myanmar’s Bamar majority, making speaking up for them a potentially politically suicidal move.

But detractors say Suu Kyi is one of the few people with the mass appeal and moral authority in Myanmar to swim against the tide on the issue.

In the short term aid agencies say they need a major international drive to provide for the huge influx of arrivals in Bangladesh’s already overstretched camps.

They have also been unable to distribute food aid in northern Rakhine since the fighting began.

Longer term solutions are even more problematic.

Suu Kyi’s government commissioned former UN chief Kofi Annan to lead a year-long review on how peace can be brought back to Rakhine.

It published its findings last month.

Among its recommendations was an end to the state-sanctioned persecution of the Rohingya and a path to citizenship for them, as well as an investment drive to alleviate poverty among both Muslims and Buddhists in Rakhine.

The report was widely welcomed internationally with calls for Myanmar’s government to swiftly implement its findings, which they have previously vowed to do.

But within hours of the report’s release, renewed fighting broke out sparking the latest exodus.

Myanmar’s Rohingya: stateless, persecuted and fleeing

Myanmar’s Rohingya: stateless, persecuted and fleeing

EU looks to soften energy bill pressures for industry, document shows

- Brussels is looking for quick fixes after companies warned they cannot compete with rivals in China and the US

- The paper said the Commission would look at network charges

BRUSSELS: The European Union is examining energy taxes, network charges and carbon costs as possible areas for short-term measures to ease pressure on industries hit by high energy prices, a document seen by Reuters showed.

Brussels is looking for quick fixes after companies warned they cannot compete with rivals in China and the US — even before this week’s surge in oil and gas prices sparked by the US-Israeli war on Iran. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has pledged to present options for EU leaders to consider at a summit on 19 March.

A Commission paper prepared for a meeting of EU Commissioners on Friday showed the bloc is exploring short-term measures to help the hardest-hit regions and sectors, without undermining longer-term climate laws meant to shift Europe to a cheaper, low-carbon energy system.

“Any proposal for legislative change will not deliver immediately and a bridge solution may be needed to reduce energy prices in the next 2-5 years until the clean transition eases pressure on power prices as already seen in some regions,” said the document, seen by Reuters.

The paper said the Commission would look at network charges — which make up about 18 percent of industrial power bills — and national taxes and levies, as well as carbon costs, which account for around 11 percent of bills.

It noted that governments are underusing existing tools to cut companies’ energy bills, including state aid to offset carbon costs and contracts for difference that guarantee industrial consumers a stable power price. The document said that if energy supplies are disrupted further, Brussels must be ready to introduce measures to encourage consumers to use less energy, as it did in 2022 when Russia slashed gas deliveries.

A Commission spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for comment.