JOHANNESBURG: Room 1026 of Johannesburg’s Central Police Station looks like any mid-century office in need of a fresh coat of paint: Dusty vertical blinds hang in the window, opening onto an unremarkable view of a chip shop, a lunchtime favorite for police officers.

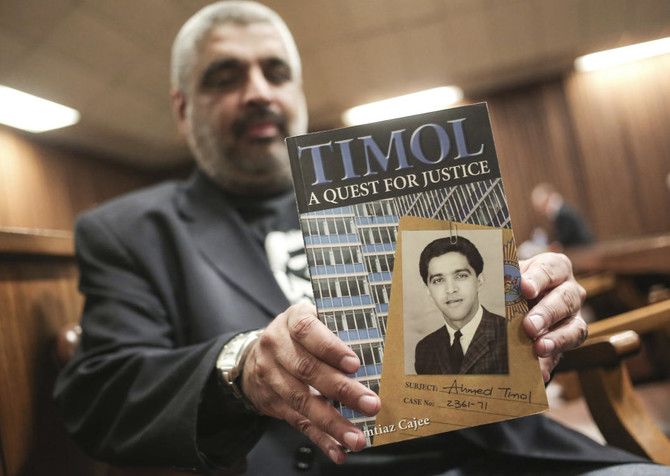

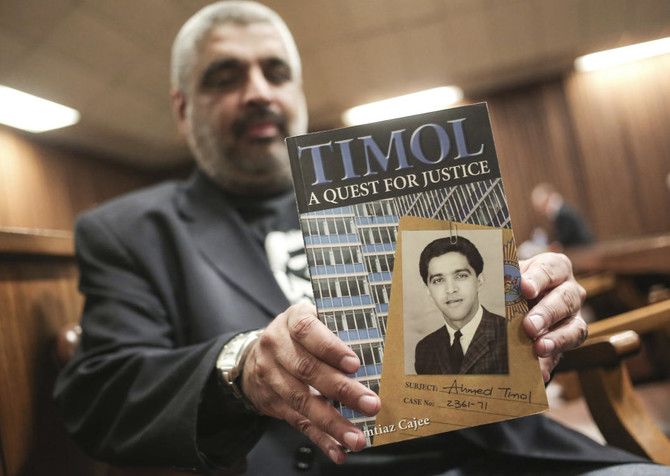

But for the past several weeks, South Africans have been riveted by an inquest into whether anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol jumped or was pushed to his death from that 10th-floor window on Oct. 27, 1971.

The hearings have dredged up dark memories of one of the country’s most infamous landmarks and legal experts say the case could set a precedent for investigating similar deaths.

For many who lived through apartheid, the system of white-minority rule that ended in the early 1990s, the building remains an ominous symbol of racial and political oppression in a country still struggling to find justice for the atrocities of a not-so-distant past.

For decades, the Johannesburg Central Police Station was known as John Vorster Square, named after the apartheid leader who oversaw the sentencing of Nelson Mandela to life in prison. Its top two floors were home to the notorious Security Branch, where anti-apartheid activists were detained and tortured. Eight people, including Timol, died while in custody in the building.

Last week Timol’s family recommended that South Africa’s government open a new criminal investigation into his death, saying police covered up having assaulted him during his detention by pushing him to his death and calling it suicide.

“What was the Security Branch covering up? It could only have been two things: the torture, and the fact that there was no suicide,” Howard Varney, an attorney for the Timol family, said during his closing arguments during the inquest at the North Gauteng High Court in Pretoria. “If there wasn’t a suicide, it must have been murder.”

Timol, a member of the South African Communist Party, was arrested at a police roadblock on Oct. 22, 1971. He died five days later after being held in Room 1026, one of 73 political detainees who died in police custody in South Africa between 1963 and 1990.

A 1972 inquest into Timol’s death upheld the police assertion that he was not tortured during his detention but jumped to his death to avoid a long prison sentence, among other reasons. The Timol family maintained he was assaulted and pushed or thrown from the building. In June, South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority opened a new inquest to re-examine the circumstances of his death.

Taking the witness stand last month, former security policeman Joao Rodrigues, who said he was in Room 1026 with Timol when he died, stood by his story. He said he was asked by colleagues to guard Timol and the activist dove out of the window before Rodrigues had the chance to stop him.

Inconsistencies in Rodrigues’ story and crucial aspects of Timol’s death cast doubt on that version of events, the family’s counsel argued. Forensic pathologists testified that Timol suffered serious injuries to his head and leg that were incompatible with his fall and that would have made it difficult for him to climb onto the window sill and jump out.

The police version of events “would have us believe that Timol was treated with care and compassion by the Security Branch,” Varney said Thursday. “None of it is believable.”

The lawyer recommended that Rodrigues be investigated for murder, accessory after the fact and perjury.

Judge Billy Mothle now will make a recommendation to state prosecutors whether a criminal case should be opened into Timol’s death, a decision that could set an important precedent for other apartheid-era cases of political prisoners’ deaths during detention.

Today, Room 1026 where Timol spent his final moments is occupied by South African border police who spend their days tackling drug smuggling and human trafficking.

The small offices on the 10th floor have not changed much in the last 40 years, observers say. Tshepiso Gloria Nkwe, a black police officer who now works in the office, admits she found it disconcerting when she learned its history. “I was scared at first,” Nkwe said.

A small plaque inside the building’s lobby lists the names of the 73 detainees who died in police custody during apartheid, including Timol’s.

Outside the building, there is little testament to its dark history. A sculpture across the street, entitled “Simakade,” or “forever standing” in the Zulu language, commemorates those who died in the building, but its plaque has been ripped off, leaving passersby to guess at its meaning.

Gerald Garner, who helped launch the popular 1 Fox development that sells craft beer and artisanal coffee in the police station’s shadow, said he finds the building “offensive.” He believes that more could be done to educate the public about its history as the new Johannesburg grows up around it.

“The fact that the building is there means you can’t avoid it,” he said.

S. Africa case is opening doors to grim apartheid deaths

S. Africa case is opening doors to grim apartheid deaths

US warships arrive off coast of Haiti

- US embassy in Haiti says flotilla sent as a part of ‘Operation Southern Spear’

- US military campaign targets alleged drug traffickers in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific

WASHINGTON: US military officials said Tuesday American warships had arrived off the coast of Haiti, as the island country’s leaders cling to power in their ongoing war against violent drug gangs.

The USS Stockdale, USCGC Stone and USCGC Diligence entered the Bay of Port-au-Prince to “reflect the United States unwavering commitment to Haiti’s security, stability and a brighter future,” the US embassy in Haiti posted on X.

The flotilla was sent “at the direction of the Secretary of War” Pete Hegseth as a part of “Operation Southern Spear,” the statement said, referring to the US military campaign targeting alleged drug traffickers in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific that has killed more than 100 people in boat strikes.

After facing years of violence and instability, Haiti is entering a new phase of political turbulence in the days before the official end of the mandate for the country’s Presidential Transitional Council on February 7.

Gang violence forced the resignation in 2024 of a previous prime minister, Ariel Henry, and the country has not held elections since 2016, with government authority collapsing in much of the country, leading to overlapping security, health and economic crises.

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, with swaths of the country under the control of rival armed gangs who carry out murders, rapes and kidnappings.

The US recently announced new visa restrictions targeting senior officials, who are accused of supporting gangs.

The USS Stockdale, USCGC Stone and USCGC Diligence entered the Bay of Port-au-Prince to “reflect the United States unwavering commitment to Haiti’s security, stability and a brighter future,” the US embassy in Haiti posted on X.

The flotilla was sent “at the direction of the Secretary of War” Pete Hegseth as a part of “Operation Southern Spear,” the statement said, referring to the US military campaign targeting alleged drug traffickers in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific that has killed more than 100 people in boat strikes.

After facing years of violence and instability, Haiti is entering a new phase of political turbulence in the days before the official end of the mandate for the country’s Presidential Transitional Council on February 7.

Gang violence forced the resignation in 2024 of a previous prime minister, Ariel Henry, and the country has not held elections since 2016, with government authority collapsing in much of the country, leading to overlapping security, health and economic crises.

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, with swaths of the country under the control of rival armed gangs who carry out murders, rapes and kidnappings.

The US recently announced new visa restrictions targeting senior officials, who are accused of supporting gangs.

© 2026 SAUDI RESEARCH & PUBLISHING COMPANY, All Rights Reserved And subject to Terms of Use Agreement.