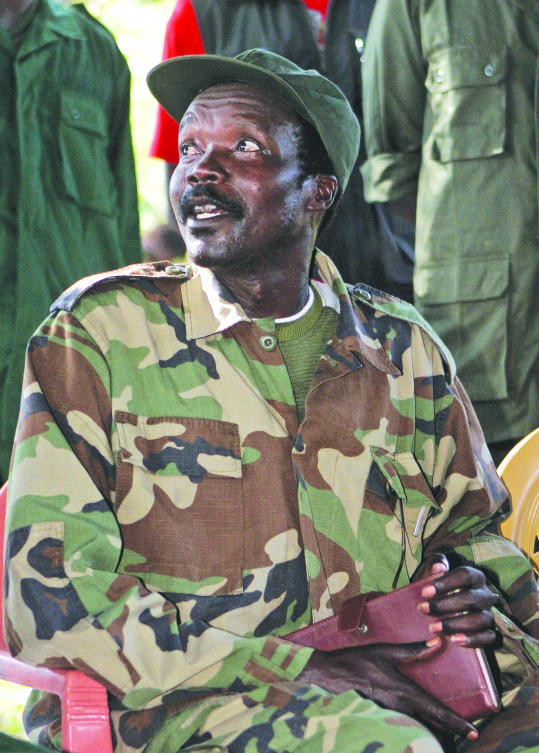

KAMPALA, Uganda: Indicted for killing thousands and kidnapping children to become soldiers and sex slaves, Joseph Kony has been Africa’s most notorious warlord for three decades. Now that the US and others are ending the international manhunt for him and his Lord’s Resistance Army, it appears Kony may never be brought to justice.

His elusiveness in the often lawless bush of central Africa is legendary. In one incident, Ugandan military forces in hot pursuit raided Kony’s hideout deep in a Congo wildlife park in 2008 and seized little but a wig and guitar he left behind.

Despite the millions of dollars spent to catch him, Kony has outlasted his hunters. That’s a blow to victims who hoped he would stand trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) where he has been charged for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

“The yearning for justice is there,” said Judith Akello, a lawmaker who represents a community in northern Uganda once hit by Kony’s rebel insurgency. “Justice is what the people demand.”

Kony became internationally notorious in 2012 when the US-based advocacy group Invisible Children made a viral video highlighting the LRA’s alleged crimes. The group is accused of killing over 100,000 people, according to the UN.

The US has offered up to $5 million for information leading to Kony’s capture.

Although scores of LRA fighters have recently surrendered or been killed, the whereabouts of Kony, now in his 50s, remain a mystery. Recent defectors from the rebel group suggest he is sick and hiding somewhere in the vast, ungoverned spaces of central Africa.

In pulling out of the military mission against the LRA, the US in March said the rebel group’s active membership is now less than 100. The US first sent about 100 special forces as military advisers to the mission in 2011, and in 2014 sent 150 Air Force personnel.

Echoing the US, Uganda’s military last month announced it was ending the manhunt and pulling out 1,500 troops because “the mission to neutralize the LRA has now been successfully achieved.”

The military withdrawal means Kony may never be caught, said some observers. Of the five LRA commanders indicted by the ICC in 2005, he is the only one still at large. One commander, Dominic Ongwen, is currently on trial at the ICC following his arrest in Central African Republic in 2015.

“Kony is the ultimate master of survival in the jungle,” said Kasper Agger, an independent researcher in Central African Republic who monitors LRA activities. “He has survived three decades of warfare and evaded capture from the most powerful and expensive military in the world.”

Kony’s rebels may continue as a “group of bandits” in sparsely populated areas of Congo and Central African Republic, where they may link up with other armed groups, said Agger. LRA rebels trade in wildlife products to support their activities, slaughtering elephants for ivory in Congo under Kony’s direct orders, according to The Enough Project.

The LRA remains a regional threat, a new UN report on sexual violence in conflict says. “The Lord’s Resistance Army continued its decade-old pattern of abduction, rape, forced marriage, forced impregnation and sexual slavery” in Central African Republic and has a presence in Congo and South Sudan, it says.

Kony has proved difficult to capture “mainly because he hides in Sudan-controlled territory” in which other African forces are not permitted to operate, said Sasha Lezhnev of the Enough Project. Sudan has denied allegations by Uganda’s government that it actively supports the LRA.

A former Catholic altar boy whose rebel movement started as a tribal uprising with aspirations of ruling Uganda according to the biblical Ten Commandments, Kony is an almost mythical figure. LRA fighters have said he has paranormal powers to read the minds of disloyal commanders.

Under military pressure, the LRA fled Uganda in 2005, moving first to Congo and then to parts of Central African Republic in a vast jungle area about the size of France. By then vastly degraded, the LRA splintered into small groups that were constantly on the move.

The rebels were up against a poorly organized Ugandan military, whose commanders in the anti-Kony campaign were accused of creating phantom soldiers on the payroll and abusing civilians.

“Kony and LRA’s nine lives were the result of their discipline,” said Angelo Izama, an analyst in Uganda who runs a think tank on regional security called Fanaka Kwawote.

Although Kony could appear bizarre, “he presided over a formidable, well-armed and loyal outfit that was quite capable of running rings around the supposedly superior soldiers sent to hunt him down,” said Matthew Green, author of “Wizard of the Nile,” a 2008 book about the LRA.

“While many people in (northern Uganda) reviled Kony for the atrocities he ordered, they were also subject to repression and abuses by (Ugandan) President Museveni’s security forces,” Green said. “Kony survived in part because there was often a deep-seated ambiguity in attitudes toward his movement among his own people, even though they were his principal victims.”

As manhunt ends, top African warlord Kony eludes justice

As manhunt ends, top African warlord Kony eludes justice

Robbers assault Chinese MP in million-euro Paris burglary

- The Chinese MP was “assaulted in his sleep and reports the theft of several pieces of jewelry ” prosecutors said

- The unauthorized use of a key could be an aggravating factor

PARIS: Thieves attacked a Chinese lawmaker at his Paris home while he was asleep, making off with jewelry and luxury goods worth several million euros, prosecutors said on Friday.

The attack took place overnight Thursday to Friday in the city’s upscale 16th arrondissement, where police found no signs of forced entry, the Paris public prosecutor’s office said.

The Chinese MP was “assaulted in his sleep and reports the theft of several pieces of jewelry and luxury goods,” prosecutors added.

The unauthorized use of a key could be an aggravating factor, it added.

The victim woke after hearing noise and was struck on the head by the burglars before they escaped, a police source said.

The suspects fled with watches, brooches and other valuables, with losses estimated between six and seven million euros ($8.3 million), the source said, adding that the Chinese deputy reported two thieves were involved.