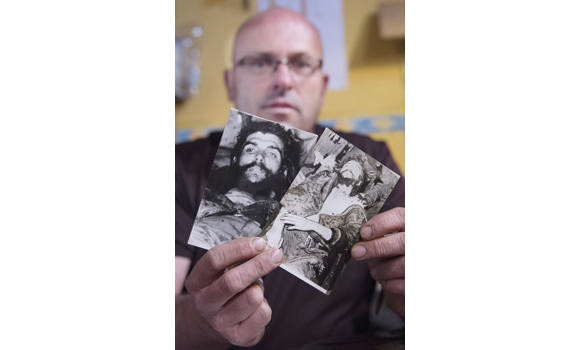

Lost for half a century, historic photographs of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara taken by an AFP photographer shortly after his execution have come to light in a small Spanish town.

The dark-bearded guerrilla leader lies in a stretcher with his dead eyes open, his bare chest stained with blood and dirt, in the eight black and white photographs taken after he was shot by the Bolivian army in October 1967.

The photographs belong to Imanol Arteaga, a local councillor in the northern Spanish town of Ricla. He inherited them from his uncle Luis Cuartero, a missionary in Bolivia in the 1960s.

“He brought back the photographs when he came for my parents’ wedding in November 1967,” said Arteaga, 45. “My aunt and my mother told me a French journalist had given them to him.”

He and his aunt found the photos among Cuartero’s belongings after the missionary died in 2012.

“I remembered he had photographs of Che Guevara and my aunt said: ‘Yes, I know where they are,” Arteaga said. “They were in boxes with a load of photos of Bolivia.”

Other rare color photographs of Guevara’s body by AFP correspondent Marc Hutten, taken after it was laid out by Bolivian soldiers, were published in the international media at the time.

But one of the newly discovered shots seems to have been taken at a different moment. In it, Che appears with matted hair and a jacket crudely buttoned around his chest.

The missionary’s stash of pictures also includes a photo purportedly of the body of Guevara’s revolutionary companion Tamara Bunke, laid on a stretcher with her face disfigured.

An Argentine-born doctor, Ernesto “Che” Guevara came to world prominence as a senior member of Fidel Castro’s revolutionary regime in Cuba.

Hunted by the CIA, he was captured by the military in Bolivia on Oct. 8, 1967, and executed the following day.

His body was displayed to the press in the village of Vallegrande before being buried in secret.

Arteaga believes it was Hutten who gave the photographs to Cuartero, possibly as a means of getting them quickly out of the country.

“He asked my uncle to take the photos because he was the only European leaving Bolivia at that moment.”

After Arteaga rediscovered the pictures, he said, “I searched on the Internet for ‘French journalist Che dead’, and Hutten’s name came up, along with some photos that are just like mine.”

After Cuartero took the photos, his family had no further contact with Hutten, who died in March 2012, shortly before the missionary himself.

Arteaga had the photographs examined by an expert who said they were printed on a kind of paper that has not been made for decades, confirming that they date to the 1960s.

“Hutten told us he had sent four or five reels of photos to AFP in Paris,” said Sylvain Estibal, current head of photography for the Europe and African region at the world news agency.

But when Hutten passed through Paris a few months after Guevara’s death, he found that “only a few of his photographs” from that batch had made it to his editors, Estibal said.

“Where the others ended up is still a mystery.”

Arteaga said he spoke to his beloved uncle every day for the last 14 years of his life, but that whole time “the photographs were left unmentioned.”

“What matters to me is that these photos were my uncle’s. They have sentimental value,” Arteaga said. “But now I realize they have historical value too.”

Historic photos of dead Che Guevara resurface in Spain

Historic photos of dead Che Guevara resurface in Spain

Eating snow cones or snow cream can be a winter delight, if done safely

- As the storm recedes, residents of lesser-affected areas might be tempted to whip up bowls of “snow cream”

- Fassnacht said he tried “snow cream” for the first time last year when some students made him some

WASHINGTON: Take two snowballs and call me in the morning?

Dr. Sarah Crockett, who specializes in emergency and wilderness medicine, doesn’t explicitly tell her patients at New Hampshire’s Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center to swallow snow, but she often prescribes more time outside. If that time includes eating a handful of ice crystals straight or adding ingredients to make snow cones and other frozen treats, she’s all for it.

“To stop and just be present and want to catch a snowflake on your tongue, or scoop up some fresh, white, untouched snow that’s collected during something as exciting as a snowstorm, I think that there’s space in our world to enjoy that,” Crockett said. “And while we need to make good choices, I think these are simple things that can bring joy.”

Getting outdoors to enjoy simple pleasures is unlikely to be front of mind for people in a 1,300-mile (2,100-kilometer) stretch of the United States where a massive weekend storm brought deep snow and bitter cold. Freezing rain and ice brought down power lines and tree limbs, leaving hundreds of thousands of homes without power or heating in the South, while snow upended road and air travel from Arkansas to New England.

As the storm recedes, residents of lesser-affected areas might be tempted to whip up bowls of “snow cream” — snow combined with milk, sugar and vanilla — after seeing techniques demonstrated on TikTok. Others might want to try “sugar on snow,” a taffy-like confection made by pouring hot maple syrup onto a plate of snow.

Despite its pristine appearance, snow isn’t always clean enough to consume. Crockett and other experts shared advice for digging in safely while digging out.

The science of snow

Whether it’s rain or snow, precipitation cleans the atmosphere, picking up pollutants as it falls, said Steven Fassnacht, a professor of snow hydrology at Colorado State University. But snowflakes pick up more impurities because they fall more slowly and have more exposed surface areas than raindrops, he said.

That means snow that falls near coal plants or factories that emit particulates into the air contains more contaminants, said Fassnacht, who was in Shinjo, Japan, last week studying the salt content of snow. He said he wouldn’t have hesitated to take a taste there because there weren’t any big industrial complexes upwind.

“Snow can be eaten, but you want to think about the trajectory. Where did that snow come from?” he said.

Timing is another consideration, according to Crockett. The first wave of snow holds the most particulate matter, she said, so waiting until a storm is well underway before putting out a bowl to collect falling snow is one precaution to take.

Ground contamination is an additional factor, experts say. Avoiding yellow snow, which may be tainted by urine or tree bark, is conventional wisdom, but it’s also a good idea to stay away from any snow pushed by snowplows and packed with road salt, deicing chemicals and debris.

Snack versus survival

What about eating snow to survive? Crockett, who oversees the wilderness medicine program at Dartmouth College’s Geisel School of Medicine, says that’s a bad idea.

The energy it takes to melt snow in your mouth as you’re eating it essentially counteracts the hydration benefit, plus it decreases your core body temperature and increases the risk of hypothermia. While outdoor enthusiasts who plan to spend days in the mountains often melt and boil snow to purify it for drinking, it shouldn’t be viewed as an immediate hydration source, she said.

“If you are disoriented on a local hike, I would say your number one priority is to try to reach out for help in any way you can, ... not ‘Can I eat enough snow?’” Crockett said.

Focus on rewards, not risks

Fassnacht, who has studied snow for more than 30 years, said he tried “snow cream” for the first time last year when some students made him some. He described it as a fun experience that got him thinking about flavors and textures, not contaminants.

“It’s a whimsical thing,” he said. “It made me think about what are the characteristics of that freshly fallen snow, and how does that change the taste sensation?”

Crockett likewise is a fan of finding inspiration and wonder in nature. She worries that overprotective parenting has contributed to anxiety in some young people, and that excessive warnings about eating snow could add to that.

“We have to strike that right balance of making sure we’re avoiding danger while not being so protective that we encourage this ‘Everything is going to harm me’ mentality, particularly for children,” she said.

Crockett has four children, including a daughter she described as a “passionate snow eater.” As the recent winter storm got underway, she asked her why she liked eating snow so much and was told, “It makes me feel connected to the Earth.”

“That is actually something that’s really important to me, that we all have this connection to nature,” Crockett said.