DUSHANBE: Tajikistan on Tuesday declared the country’s top opposition party a terrorist organization after the government accused it of being behind bloody street battles that left dozens dead.

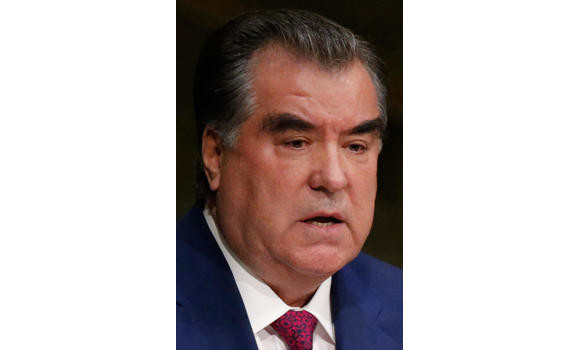

The volatile and impoverished Central Asian state’s supreme court accepted a request from the state prosecutor to close the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT). The IRPT was the only registered faith-based party in the former Soviet Union and was one of the few potential sources of genuine opposition to President Emomali Rakhmon’s two-decade rule.

The legal ban on the party is seen by analysts as the culmination of government efforts to sideline the IRPT, which was seen as an umbrella opposition bloc for moderate Muslims and secular-minded Tajiks.

“The aim of the IRPT was the overthrow of the constitutional order in Tajikistan,” said a statement from the Supreme Court, which has blacklisted it as a terrorist organization.

“In the last five years, 45 members of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan have committed serious crimes.” The ban comes after an upsurge in violence left more than 40 people in Tajikistan this month.

The authorities said that more than 40 people had died in violence that raged in the country for nearly two weeks by the time deputy defense minister-turned-rebel-leader Abduhalim Nazarzoda was killed in a military operation.

The government accused the party via state-controlled media of plotting the attacks in the capital Dushanbe and the provincial town of Vahdat for five years.

IRPT has denied links to the violence which saw at least 13 party activists detained by police earlier this month on charges the government has yet to officially clarify.

A lawyer representing the detained IRPT activists has also been arrested on fraud and forgery charges, the government said this week.

Many independent analysts have cast doubt on the allegations levelled at the party.

Human Rights Watch, the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, and the Association for Human Rights in Central Asia this month accused the authorities of launching “a full-scale assault on dissent in Tajikistan.” The party was viewed as having been effectively banned in August — before the outbreak of the violence — when authorities sealed off its headquarters and the Justice Ministry declared its activities “illegal.”

Tajikistan shuts down Islamic opposition party

Tajikistan shuts down Islamic opposition party

Rohingya refugees hope new leaders can pave a path home

- Some 1.7 million Rohingya Muslims displaced in Myanmar's military crackdown live in squalid camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh

COX’S BAZAR, Bangladesh: Rohingya refugees living in squalid camps in Bangladesh have elected a leadership council, hoping it can improve conditions and revive efforts to secure their return home to Myanmar.

Spread over 8,000 acres in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, the camps are home to 1.7 million members of the stateless group, many of whom fled a 2017 military crackdown that is now subject to a genocide probe at the UN court.

In July, the refugees held their first elections since their influx began eight years ago, resulting in the formation of the United Council of Rohang (UCR).

“They are working to take us home,” said Khairul Islam, 37, who back home had a thriving timber business.

The new council has brought him a glimmer of hope amid an uncertain future.

“We can hardly breathe in these cramped camp rooms... all our family members live in a single room,” he said.

“It’s unbearably hot inside. Back in Myanmar, we didn’t even need a ceiling fan. In summer, we used to sit under tall trees,” Islam said, his eyes welling up.

More than 3,000 voters from across 33 refugee camps cast their ballots to elect an executive committee and five rotating presidents to focus on human rights, education and health.

Addressing a gathering at one of the camps, UCR president Mohammad Sayed Ullah urged refugees not to forget the violence that forced the mostly Muslim group to flee Myanmar’s Rakhine state.

“Never forget that we left our parents’ graves behind. Our women died on the way here. They were tortured and killed... and some drowned at sea,” said Sayed Ullah, dressed in a white full-sleeved shirt and lungi.

“We must prepare ourselves to return home,” he said, prompting members of the audience to nod in agreement.

A seat at the table

“UCR wants to emerge as the voice of the Rohingyas on the negotiation table,” Sayed Ullah later told AFP.

“It’s about us, yet we were nowhere as stakeholders.”

The council is not the first attempt to organize Rohingya refugees.

Several groups emerged after 2017, including the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights, once led by prominent activist Mohib Ullah.

But he was murdered in 2021.

And even before that, many organizations were shut down after a major 2019 rally, when the Rohingya said they would go home only with full rights and safety guarantees.

“Some newspapers misrepresented us, claiming we wanted to stay permanently in Bangladesh,” Sayed Ullah said.

“Many organizers were detained. The hardest blow was the assassination of Mohib Ullah.”

But trust is slowly building up again among the Rohingya crammed in the camps in Cox’s Bazar.

“Of course we will return home,” said 18-year-old Mosharraf, who fled the town of Buthidaung with his family.

“UCR will negotiate for better education. If we are better educated, we can build global consensus for our return,” he told AFP.

Security threats

Many refugees have started approaching the body with complaints against local Rohingya leaders, reflecting a slow but noticeable shift in attitudes.

On a recent sunny morning, an AFP reporter saw more than a dozen Rohingya waiting outside the UCR office with complaints.

Some said they were tortured while others reported losing small amounts of gold they had carried while fleeing their homes.

Analysts say it remains unclear whether the new council can genuinely represent the Rohingya or if it ultimately serves the interests of Bangladeshi authorities.

“The UCR ‘elections’ appear to have been closely controlled by the authorities,” said Thomas Kean, senior consultant at the International Crisis Group.

Security threats also loom large, undermining efforts to forge political dialogue.

Armed groups like the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army and Rohingya Solidarity Organization continue to operate in the camps.

A report by campaign group Fortify Rights said at least 65 Rohingyas were killed in 2024.

“Violence and killings in the Rohingya camps need to stop, and those responsible must be held to account,” the report quoted activist John Quinley as saying.