VILNIUS: Belarusian street protest leader Maria Kolesnikova and Nobel Prize winner Ales Bialiatski walked free on Saturday with 121 other political prisoners released in an unprecedented US-brokered deal.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko has locked up thousands of his opponents, critics and protesters since the 2020 election, which rights groups said was rigged and which triggered weeks of protests that almost toppled him.

The charismatic Kolesnikova was the star of the 2020 movement that presented the most serious challenge to Lukashenko in his 30-year rule.

She famously ripped up her passport as the KGB tried to deport her from the country.

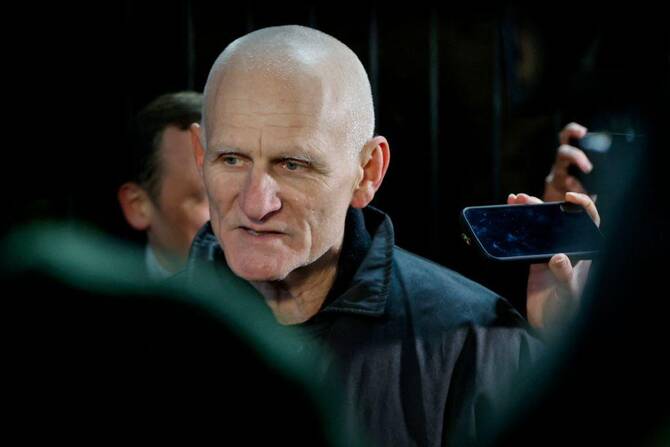

Bialiatski — a 63-year-old veteran rights defender and 2022 Nobel Peace Prize winner — is considered by Lukashenko to be a personal enemy. He has documented rights abuses in the country, a close ally of Moscow, for decades.

Bialiatski stressed he would carry on fighting for civil rights and freedom for political prisoners after his surprise release, which he called a “huge emotional shock.”

“Our fight continues, and the Nobel Prize was, I think, a certain acknowledgement of our activity, our aspirations that have not yet come to fruition,” he told media in an interview from Vilnius.

“Therefore the fight continues,” he added.

He was awarded the prize in 2022 while already in jail.

After being taken out of prison, he said he was put on a bus and blindfolded until they reached the border with Lithuania.

His wife, Natalia Pinchuk, told AFP that her first words to him on his release were: “I love you.”

- ‘All be free’ -

Most of those freed, including Kolesnikova, were unexpectedly taken to Ukraine, surprising their allies who had been waiting for all of them in Lithuania.

She called for all political prisoners to be released.

“I’m thinking of those who are not yet free, and I’m very much looking forward to the moment when we can all embrace, when we can all see one another, and when we will all be free,” she said in a video interview with a Ukrainian government agency.

Hailing Bialiatski’s release, the Nobel Committee told AFP there were still more than 1,200 political prisoners inside the country.

“Their continued detention starkly illustrates the ongoing, systemic repression in the country,” said chairman Jorgen Watne Frydnes.

EU chief Ursula von der Leyen said their release should “strengthen our resolve... to keep fighting for all remaining prisoners behind bars in Belarus because they had the courage to speak truth to power.”

Jailed opponents of Lukashenko are often held incommunicado in a prison system notorious for its secrecy and harsh treatment.

There had been fears for the health of both Bialiatski and Kolesnikova while they were behind bars, though in interviews Saturday they both said they felt okay.

The deal was brokered by the United States, which has pushed for prisoners to be freed and offered some sanctions relief in return.

- Potash relief -

An envoy of US President Donald Trump, John Coale, was in Minsk this week for talks with Lukashenko.

He told reporters from state media that Washington would remove sanctions on the country’s potash industry, without providing specific details.

A US official separately told AFP that one American citizen was among the 123 released.

Minsk also freed Viktor Babariko, an ex-banker who tried to run against Lukashenko in the 2020 presidential election but was jailed instead.

Kolesnikova was part of a trio of women, including Svetlana Tikhanovskaya who stood against Lukashenko and now leads the opposition in exile, who headed the 2020 street protests.

She was serving an 11-year sentence in a prison colony.

In 2020, security services had put a sack over her head and drove her to the Ukrainian border. But she ripped up her passport, foiling the deportation plan, and was placed under arrest.

Former prisoners from the Gomel prison where she was held have told AFP she was barred from talking to other political prisoners and regularly thrown into harsh punishment cells.

An image of Kolesnikova making a heart shape with her hands became a symbol of anti-Lukashenko protests.

Bialiatski founded Viasna in the 1990s, two years after Lukashenko became president.