NEW YORK: Sean “Diddy” Combs ‘ former personal assistant testified Thursday that the hip-hop mogul sexually assaulted her, threw her into a swimming pool, dumped a bucket of ice on her and slammed a door against her arm during a torturous eight-year tenure.

The woman, testifying at Combs’ sex trafficking trial under the pseudonym “Mia,” said Combs put his hand up her dress and forcibly kissed her at his 40th birthday party in 2009, forced her to perform oral sex while she helped him pack for a trip and raped her in guest quarters at his Los Angeles home in 2010 after climbing into her bed.

“I couldn’t tell him ‘no’ about anything,” Mia said, telling jurors she felt “terrified and confused and ashamed and scared” when Combs raped her. The assaults, she said, were unpredictable: “always random, sporadic, so oddly spaced out where I would think they would never happen again.”

If she hadn’t been called to testify, Mia said, “I was going to die with this. I didn’t want anyone to know ever.”

Speaking slowly and haltingly, Mia portrayed Combs as a controlling taskmaster who put his desires above the wellbeing of staff and loved ones. She said Combs berated her for mistakes, even ones other employees made, and piled on so many tasks she didn’t sleep for days.

“It was chaotic. It was toxic,” said Mia, who worked for Combs from 2009 to 2017, including a stint as an executive at his film studio. “It could be exciting. The highs were really high and the lows were really low.”

Asked what determined how her days would unfold, Mia said: “Puff’s mood,” using one of his many nicknames.

Mia said employees were always on edge because Combs’ mood could change “in a split second” causing everything to go from “happy to chaotic.” She said Combs once threw a computer at her when he couldn’t get a Wi-Fi connection.

Her testimony echoed that of Combs’ other personal assistants and his longtime girlfriend Cassie, who said he was demanding, mercurial and prone to violence. She is the second of three women testifying that Combs sexually abused them.

Cassie, an R&B singer whose legal name is Casandra Ventura, testified for four days during the trial’s first week, telling jurors Combs subjected her to hundreds of “freak-offs” — drug-fueled marathons in which she said she engaged in sex acts with male sex workers while Combs watched, filmed and coached them.

A third woman, “Jane,” is expected to testify about participating in freak-offs. Judge Arun Subramanian has permitted some of Combs’ sexual abuse accusers to testify under pseudonyms for their privacy and safety.

The Associated Press does not identify people who say they’re victims of sexual abuse unless they choose to make their names public, as Cassie has done.

Combs, 55, has pleaded not guilty to sex trafficking and racketeering charges. His lawyers concede he could be violent, but he denies using threats or his clout to commit abuse.

Mia testified that she saw Combs beat Cassie numerous times, detailing a brutal assault at Cassie’s Los Angeles home in 2013 that the singer and her longtime stylist Deonte Nash also recounted in their testimony. Mia said she was terrified Combs was going to kill them all, describing the melee as “a little tornado.”

The witness recalled jumping on Combs’ back in an attempt to stop him from hurting Nash and Cassie. Mia said Combs threw her into a wall and slammed Cassie’s head into a bed corner, causing a deep, bloody gash on the singer’s forehead. Other times, she said, Combs’ abuse caused Cassie black eyes and fat lips.

Mia said Combs sometimes had her working for up to five days at a time without rest as he hopped from city to city for club appearances and other engagements, and she started relying on her ADHD medication, the stimulant Adderall, as a sleep substitute.

Combs, with residences in Miami, Los Angeles and the New York area, let Mia and other employees stay in his guest houses — but she wasn’t allowed to leave without his permission and couldn’t lock the doors, she testified.

“This is my house. No one locks my doors,” Combs said, according to Mia.

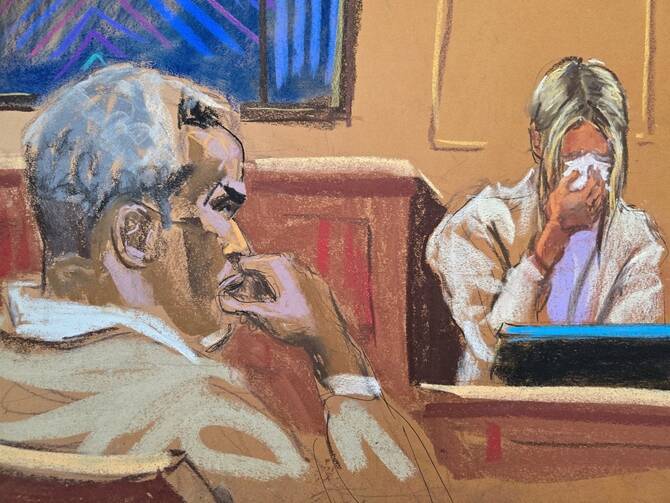

Mia didn’t appear to make eye contact with Combs, who sat back in his chair and looked forward, sometimes with his hands folded in front him, as she testified. Occasionally, he leaned over to speak with one of his lawyers or donned glasses to read exhibits. Mia kept her head down as she left the courtroom for breaks.

She testified that she remains friends with Cassie.

Ex-assistant testifies Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs sexually assaulted her and used violence to get his way

https://arab.news/wwujx

Ex-assistant testifies Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs sexually assaulted her and used violence to get his way

- “I was going to die with this. I didn’t want anyone to know ever.”

How TV shows like ‘Mo’ and ‘Muslim Matchmaker’ allow Arab and Muslim Americans to tell their stories

How TV shows like ‘Mo’ and ‘Muslim Matchmaker’ allow Arab and Muslim Americans to tell their stories

- In addition to “Mo,” shows like “Muslim Matchmaker,” hosted by matchmakers Hoda Abrahim and Yasmin Elhady, connect Muslim Americans from around the country with the goal of finding a spouse

COLUMBUS, Ohio: Whether it’s stand-up comedy specials or a dramedy series, when Muslim American Mo Amer sets out to create, he writes what he knows.

The comedian, writer and actor of Palestinian descent has received critical acclaim for it, too. The second season of Amer’s “Mo” documents Mo Najjar and his family’s tumultuous journey reaching asylum in the United States as Palestinian refugees.

Amer’s show is part of an ongoing wave of television from Arab American and Muslim American creators who are telling nuanced, complicated stories about identity without falling into stereotypes that Western media has historically portrayed.

“Whenever you want to make a grounded show that feels very real and authentic to the story and their cultural background, you write to that,” Amer told The Associated Press. “And once you do that, it just feels very natural, and when you accomplish that, other people can see themselves very easily.”

At the start of its second season, viewers find Najjar running a falafel taco stand in Mexico after he was locked in a van transporting stolen olive trees across the US-Mexico border. Najjar was trying to retrieve the olive trees and return them to the farm where he, his mother and brother are attempting to build an olive oil business.

Both seasons of “Mo” were smash hits on Netflix. The first season was awarded a Peabody. His third comedy special on Netflix, “Mo Amer: Wild World,” premiered in October.

Narratively, the second season ends before the Hamas attack in Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, but the series itself doesn’t shy away from addressing Israeli-Palestinian relations, the ongoing conflict in Gaza or what it’s like for asylum seekers detained in US Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers.

In addition to “Mo,” shows like “Muslim Matchmaker,” hosted by matchmakers Hoda Abrahim and Yasmin Elhady, connect Muslim Americans from around the country with the goal of finding a spouse.

The animated series, “#1 Happy Family USA,” created by Ramy Youssef, who worked with Amer to create “Mo,” and Pam Brady, follows an Egyptian American Muslim family navigating life in New Jersey after the 9/11 terrorists attack in New York.

Current events have an influence

The key to understanding the ways in which Arab or Muslim Americans have been represented on screen is to be aware of the “historical, political, cultural and social contexts” in which the content was created, said Sahar Mohamed Khamis, a University of Maryland professor who studies Arab and Muslim representation in media.

After the 9/11 attacks, Arabs and Muslims became the villains in many American films and TV shows. The ethnic background of Arabs and the religion of Islam were portrayed as synonymous, too, Khamis said. The villain, Khamis said, is often a man with brown skin with an Arab-sounding name.

A show like “Muslim Matchmaker” flips this narrative on its head, Elhady said, by showing the ethnic diversity of Muslim Americans.

“It’s really important to have shows that show us as everyday Americans,” said Elhady, who is Egyptian and Libyan American, “but also as people that live in different places and have kind of sometimes dual realities and a foot in the East and a foot in the West and the reality of really negotiating that context.”

Before 9/11, people living in the Middle East were often portrayed to Western audiences as exotic beings, living in tents in the desert and riding camels. Women often had little to no agency in these media depictions and were “confined to the harem” — a secluded location for women in a traditional Muslim home.

This idea, Khamis said, harkens back to the term “orientalism,” which Palestinian American academic, political activist and literary critic Edward Said coined in his 1978 book of the same name.

Khamis said, pointing to countries like Britain and France, the portrayal in media of people from the region was “created and manufactured, not by the people themselves, but through the gaze of an outsider. The outsiders in this case, he said, were the colonial/imperialist powers that were actually controlling these lands for long periods of time.”

Among those who study the ways Arabs have been depicted on Western television, a common critique is that the characters are “bombers, billionaires or belly dancers,” she said.

The limits of representation

Sanaz Alesafar, executive director of Storyline Partners and an Iranian American, said she has seen some “wins” with regard to Arab representation in Hollywood, noting the success of “Mo,” “Muslim Matchmaker” and “#1 Happy Family USA.” Storyline Partners helps writers, showrunners, executives and creators check the historical and cultural backgrounds of their characters and narratives to assure they’re represented fairly and that one creator’s ideas don’t infringe upon another’s.

Alesafar argues there is still a need for diverse stories told about people living in the Middle East and the English-speaking diaspora, written and produced by people from those backgrounds.

“In the popular imagination and popular culture, we’re still siloed in really harmful ways,” she said. “Yes, we’re having these wins and these are incredible, but that decision-making and centers of power still are relegating us to these tropes and these stereotypes.”

Deana Nassar, an Egyptian American who is head of creative talent at film production company Alamiya Filmed Entertainment, said it’s important for her children to see themselves reflected on screen “for their own self image.” Nassar said she would like to see a diverse group of people in decision-making roles in Hollywood. Without that, it’s “a clear indication that representation is just not going to get us all the way there,” she said.

Representation can impact audiences’ opinions on public policy, too, according to a recent study by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. Results showed that the participants who witnessed positive representation of Muslims were less likely to support anti-democratic and anti-Muslim policies compared to those who viewed negative representations.

For Amer, limitations to representation come from the decision-makers who greenlight projects, not from creators. He said the success of shows like his and others are a “start,” but he wants to see more industry recognition for his work and the work of others like him.

“That’s the thing, like just keep writing, that’s all it’s about,” he said. “Just keep creating and keep making and thankfully I have a really deep well for that, so I’m very excited about the next things,” he said.