KHARTOUM: It had been nearly two years since AFP journalist Abdelmoneim Abu Idris Ali set foot in his home in war-torn Khartoum, after the sound of children playing in the street gave way to the fearsome fire of machine guns.

Sudan’s once-peaceful capital awoke to the sound of bombs and gunfire on April 15, 2023 as war broke out between its two most powerful generals — army chief Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan and his former deputy Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, who commands the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Bombs tore through homes, fighters took over the streets and hundreds of thousands scrambled to escape — among them Abdelmoneim, his wife, his son and three daughters.

Since then they have been displaced five times — fleeing each time the front line closed in.

Eventually the 59-year-old journalist sent his family to safety in another African country while he settled down to work alone from Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

Then last month he was able to briefly return to his home in Khartoum North during a reporting trip escorted by the army after it recaptured the city.

He found his beloved neighborhood, known as Bahri, abandoned.

“The whole place is cloaked in silence, no grocery store chit-chats, no boisterous games of football on the corner, nothing,” he said.

“The last time I was here, the neighbors were all in the street saying goodbye, praying for each other’s safety, promising we would meet again soon.”

Now their doors hung ajar, beds dragged out onto the street, apparently by RSF fighters who used them to sleep in the open air.

Since the war broke out, the paramilitaries have been notorious for taking over and looting homes, selling the contents or taking it for themselves.

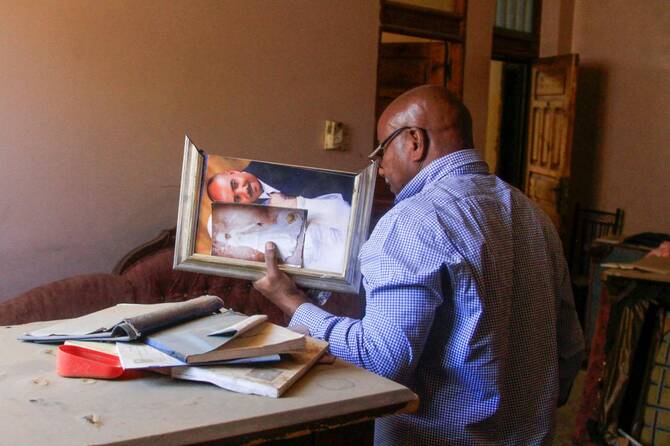

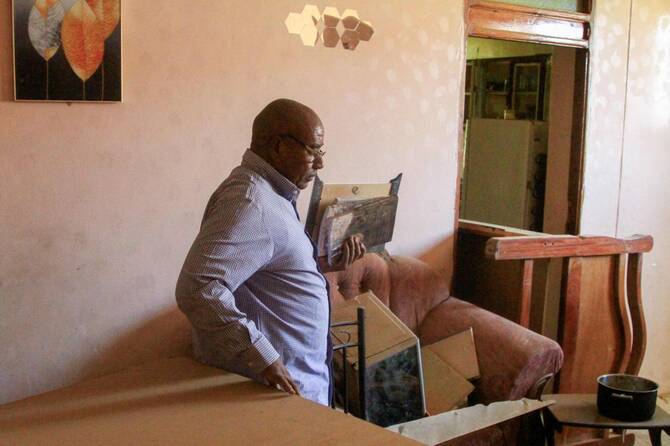

When he got to his landing, Abdelmoneim braced himself for what he would find inside.

“It was like an earthquake had hit. The furniture was upside-down and thrown around, pieces shattered on the ground,” he said.

He clambered slowly from room to room, taking in the damage.

The couch was pocked with burn marks where the fighters had put out cigarette after cigarette.

His daughters’ closets were ripped open and emptied of every last dress.

And on the floor of his office, lying among the tattered remains of his library, was a photo of his wedding to his wife Nahla, with her image torn out.

“I don’t get what they have against my books and my wedding photos,” he said.

“I knew they had stolen furniture. I couldn’t imagine they would destroy everything else.”

In March, the army recaptured Khartoum, to the joy of millions of displaced Sudanese anxious to return to their homes.

“But my girls say they never want to come back,” Abdelmoneim said.

“How can they ever forget sleeping huddled together in the living room, terrified by the sound of every air strike?“

Abdelmoneim shudders at the thought of the horrors they have seen since.

“When we were leaving Khartoum, there were bodies lying in the street and an old man standing over them, trying to keep a plastic sheet in place.

“When I stopped to ask him if he was okay, he said, ‘I’m trying to keep the dogs away.’ I wish my kids had never heard that.”

For seven months, Abdelmoneim tried to wait out the fighting in Wad Madani, just south of Khartoum, hoping against hope they could go home.

“The moment I realized this wouldn’t end for years was when the war came to Wad Madani,” he said.

Again they took everything they could carry, and again they joined a wave of hundreds of thousands of people running away, this time on foot, heading east.

The veteran journalist and his wife made the painful choice to separate the family — she and the children would go to another country; and he would go to Port Sudan on the Red Sea, home to the United Nations, the army-aligned government and hundreds of thousands of displaced people.

Abdelmoneim, like countless Sudanese caught in the war’s crossfire, has lost family members, his life savings and any hope for the future.

“This war has taken everything from us,” he said.

“And everything they haven’t taken, they’ve destroyed.”

For years he had been building up a tiny homestead on the outskirts of Khartoum, lined with fruit trees and a few simple crops he could tend when he retired. The RSF destroyed it in their rampage.

His family’s home and land, in the agricultural state of Al-Jazira, were looted and cut off from power and water — his relatives left starving and powerless to defend themselves against the RSF’s predations.

Now both Al-Jazira and Khartoum are under army control but the war, and the suffering it has wrought, is far from over.

Tens of thousands have been killed and more than 12 million uprooted, including almost four million who fled to other countries.

Hundreds of thousands are returning to areas recaptured by the army, choosing destitution at home over displacement, but most of these areas still lack clean water, electricity and health care.

Famine still stalks Sudan, with around 638,000 people already in famine and eight million on the brink of mass starvation.

The country remains divided, and the RSF — in control of nearly all of the western region of Darfur and, with its allies, parts of the south — has not given up the fight.

In recent weeks, the paramilitaries have killed hundreds of people in famine-stricken displacement camps, while RSF chief Dagalo has announced a rival administration to rule over the ashes.

For many like Abdelmoneim, even their modest dreams now seem impossible.

“If this war ends tomorrow, all I want is to be somewhere quiet and safe with my family, farming in peace.”

‘War has taken everything’: AFP reporter returns home to Khartoum

https://arab.news/bznsb

‘War has taken everything’: AFP reporter returns home to Khartoum

- Bombs tore through homes, fighters took over the streets and hundreds of thousands scrambled to escape

- Since the war broke out, the paramilitaries have been notorious for taking over and looting homes, selling the contents or taking it for themselves

Syrian army pushes into Aleppo district after Kurdish groups reject withdrawal

- Two Syrian security officials told Reuters the ceasefire efforts had failed and that the army would seize the neighborhood by force

ALEPPO, Syria: The Syrian army said it would push into the last Kurdish-held district of Aleppo city on Friday after Kurdish groups there rejected a government demand for their fighters to withdraw under a ceasefire deal.

The violence in Aleppo has brought into focus one of the main faultlines in Syria as the country tries to rebuild after a devastating war, with Kurdish forces resisting efforts by President Ahmed Al-Sharaa’s Islamist-led government to bring their fighters under centralized authority.

At least nine civilians have been killed and more than 140,000 have fled their homes in Aleppo, where Kurdish forces are trying to cling on to several neighborhoods they have run since the early days of the war, which began in 2011.

HIGHLIGHTS

• Standoff pits government against Kurdish forces

• Sharaa says Kurds are ‘fundamental’ part of Syria

• More than 140,000 have fled homes due to unrest

• Turkish, Syrian foreign ministers discuss Aleppo by phone

ِA ceasefire was announced by the defense ministry overnight, demanding the withdrawal of Kurdish forces to the Kurdish-held northeast. That would effectively end Kurdish control over the pockets of Aleppo that Kurdish forces have held.

CEASEFIRE ‘FAILED,’ SECURITY OFFICIALS SAY

But in a statement, Kurdish councils that run Aleppo’s Sheikh Maksoud and Ashrafiyah districts said calls to leave were “a call to surrender” and that Kurdish forces would instead “defend their neighborhoods,” accusing government forces of intensive shelling.

Hours later, the Syrian army said that the deadline for Kurdish fighters to withdraw had expired, and that it would begin a military operation to clear the last Kurdish-held neighborhood of Sheikh Maksoud.

Two Syrian security officials told Reuters the ceasefire efforts had failed and that the army would seize the neighborhood by force.

The Syrian defense ministry had earlier carried out strikes on parts of Sheikh Maksoud that it said were being used by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to launch attacks on the “people of Aleppo.” It said on Friday that SDF strikes had killed three army soldiers.

Kurdish security forces in Aleppo said some of the strikes hit a hospital, calling it a war crime. The defense ministry disputed that, saying the structure was a large arms depot and that it had been destroyed in the resumption of strikes on Friday.

It posted an aerial video that it said showed the location after the strikes, and said secondary explosions were visible, proving it was a weapons cache.

Reuters could not immediately verify the claim.

The SDF is a powerful Kurdish-led security force that controls northeastern Syria. It says it withdrew its fighters from Aleppo last year, leaving Kurdish neighborhoods in the hands of the Kurdish Asayish police.

Under an agreement with Damascus last March the SDF was due to integrate with the defense ministry by the end of 2025, but there has been little progress.

FRANCE, US SEEK DE-ESCALATION

France’s foreign ministry said it was working with the United States to de-escalate.

A ministry statement said President Emmanuel Macron had urged Sharaa on Thursday “to exercise restraint and reiterated France’s commitment to a united Syria where all segments of Syrian society are represented and protected.”

A Western diplomat told Reuters that mediation efforts were focused on calming the situation and producing a deal that would see Kurdish forces leave Aleppo and provide security guarantees for Kurds who remained.

The diplomat said US envoy Tom Barrack was en route to Damascus. A spokesperson for Barrack declined to comment. Washington has been closely involved in efforts to promote integration between the SDF — which has long enjoyed US military support — and Damascus, with which the United States has developed close ties under President Donald Trump.

The ceasefire declared by the government overnight said Kurdish forces should withdraw by 9 a.m. (0600 GMT) on Friday, but no one withdrew overnight, Syrian security sources said.

Barrack had welcomed what he called a “temporary ceasefire” and said Washington was working intensively to extend it beyond the 9 a.m. deadline. “We are hopeful this weekend will bring a more enduring calm and deeper dialogue,” he wrote on X.

TURKISH WARNING

Turkiye views the SDF as a terrorist organization linked to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party and has warned of military action if it does not honor the integration agreement.

Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan, speaking on Thursday, expressed hope that the situation in Aleppo would be normalized “through the withdrawal of SDF elements.”

Though Sharaa, a former Al-Qaeda commander who belongs to the Sunni Muslim majority, has repeatedly vowed to protect minorities, bouts of violence in which government-aligned fighters have killed hundreds of Alawites and Druze have spread alarm in minority communities over the last year.

The Kurdish councils in Aleppo said Damascus could not be trusted “with our security and our neighborhoods,” and that attacks on the areas aimed to bring about displacement.

Sharaa, in a phone call with Iraqi Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani on Friday, affirmed that the Kurds were “a fundamental part of the Syrian national fabric,” the Syrian presidency said.

Neither the government nor the Kurdish forces have announced a toll of casualties among their fighters from the recent clashes.