LONDON: As Lebanon faces up to its broken finances, neglected infrastructure and postwar reconstruction, the appointment of Karim Souaid as the new central bank governor marks an important step toward economic recovery.

On March 27, after weeks of government wrangling, 17 of the cabinet’s 24 ministers voted to name asset manager Souaid as governor of Banque du Liban, the country’s National News Agency reported.

Souaid replaces interim governor Wassim Mansouri, who led the central bank after Riad Salameh’s controversial 30-year tenure ended in 2023 — almost a year before his arrest on embezzlement, money laundering and fraud charges tied to financial commissions.

The choice of candidate was critical for both domestic and international stakeholders, as the role is key to enacting the financial reforms required by donors, including the International Monetary Fund, in exchange for a bailout.

Souaid’s appointment comes with high expectations. His priorities include restarting talks with the IMF, negotiating sovereign debt restructuring and rebuilding foreign exchange reserves.

Nafez Zouk, a sovereign analyst at Aviva Investors, told Arab News that the new central bank chief “needs to be able to demonstrate some commitment to the IMF’s approach for restructuring the banking sector.”

Karim Souaid was appointed as the new central bank governor. (Supplied)

Souaid brings extensive experience in privatization, banking regulations and structuring large-scale economic transitions. He is also the founder and managing partner of the Bahrain-based private investment firm Growthgate Equity Partners.

However, his success as central bank chief will depend on international support, as Western nations and financial institutions have linked aid to sweeping economic reforms, including banking sector restructuring.

Last year, the EU pledged €1 billion ($1.08 billion) to help Lebanon curb refugee flows to Europe. Half was paid in August, while the rest is contingent on “some conditions,” EU Commissioner Dubravka Suica said during a February visit.

“The main precondition is the restructure of the banking sector ... and a good agreement with the International Monetary Fund,” she said after meeting Lebanese President Joseph Aoun.

However, critics have raised concerns about Souaid’s ties to Lebanon’s financial elite and members of the entrenched ruling class, fearing that his policies might favor the banking sector over broader economic reform, local media reported.

Prime Minister Nawaf Salam has also expressed reservations about Souaid’s appointment, saying the central bank chief “must adhere, from today, to the financial policy of our reformist government… on negotiating a new program with the IMF, restructuring the banks and presenting a comprehensive plan” to preserve depositors’ rights.

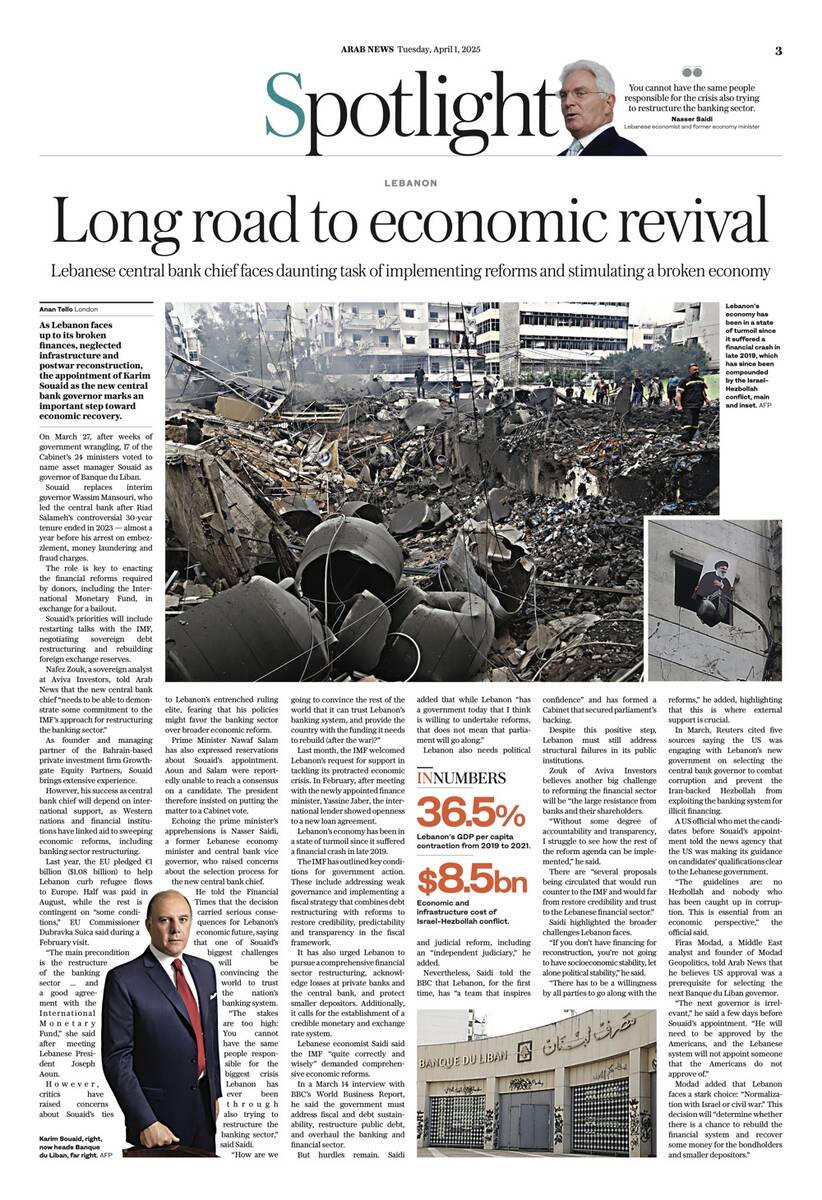

An excavator removes wreckage at site of an Israeli airstrike that targeted a house in the southern Lebanese village of Kfar Tibnit. (AFP)

Before Souaid’s appointment, Aoun and Salam were unable to reach a consensus on a candidate, according to local media reports. The president therefore insisted on putting the matter to a Cabinet vote.

Echoing the prime minister’s apprehensions is Nasser Saidi, a former Lebanese economy minister and central bank vice governor, who raised concerns about the selection process for the new central bank chief, warning that powerful interest groups may have too much influence.

He told the Financial Times that the decision carried serious consequences for Lebanon’s economic future, saying that one of Souaid’s biggest challenges will be convincing the world to trust the nation’s banking system enough to risk investing in its recovery.

“The stakes are too high: You cannot have the same people responsible for the biggest crisis Lebanon has ever been through also trying to restructure the banking sector,” said Saidi, who served as first vice governor of the Banque du Liban for two consecutive terms.

“How are we going to convince the rest of the world that it can trust Lebanon’s banking system, and provide the country with the funding it needs to rebuild (after the war)?”

The World Bank ranks the economic collapse among the worst globally since the mid-19th century. (AFP/File)

Last month, the IMF welcomed Lebanon’s request for support in tackling its protracted economic crisis. In February, after meeting with the newly appointed finance minister, Yassine Jaber, the international lender showed openness to a new loan agreement.

Lebanon’s economy has been in a state of turmoil since it suffered a financial crash in late 2019, compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Beirut port blast of August 2020 and the 14-month Israel-Hezbollah conflict.

The national currency has lost more than 90 percent of its value and food prices have soared almost tenfold since May 2019. Citizens have struggled to access their savings since banks imposed strict withdrawal limits, effectively trapping deposits.

Lebanon’s prolonged crisis, triggered by widespread corruption and excessive spending by the ruling elite, has driven the country from upper-middle-income to lower-middle-income status, with gross domestic product per capita falling 36.5 percent from 2019 to 2021.

The World Bank ranks the economic collapse among the worst globally since the mid-19th century.

The Israel-Hezbollah war, which began Oct. 8, 2023, and concluded with a fragile ceasefire in November 2024, is estimated to have caused $3.4 billion in damage to Lebanese infrastructure, with economic losses of up to $5.1 billion.

Combined, these figures total 40 percent of Lebanon’s GDP.

The IMF has outlined key conditions for government action. These include addressing weak governance and implementing a fiscal strategy that combines debt restructuring with reforms to restore credibility, predictability and transparency in the fiscal framework.

It has also urged Lebanon to pursue a comprehensive financial sector restructuring, acknowledge losses at private banks and the central bank, and protect smaller depositors. Additionally, it calls for the establishment of a credible monetary and exchange rate system.

Lebanese economist Saidi said that the IMF “quite correctly and wisely” demanded comprehensive economic reforms.

INNUMBERS

• 36.5% Lebanon’s GDP per capita contraction from 2019 to 2021.

• $8.5bn Economic and infrastructure cost of Israel-Hezbollah conflict.

In a March 14 interview with BBC’s “World Business Report,” he said that the government must address fiscal and debt sustainability, restructure public debt, and overhaul the banking and financial sector.

But hurdles remain. Saidi added that while Lebanon “has a government today that I think is willing to undertake reforms, that does not mean that parliament will go along.”

Lebanon also needs political and judicial reform, including an “independent judiciary,” he added.

Nevertheless, Saidi told the BBC that Lebanon, for the first time, has “a team that inspires confidence” and has formed a cabinet that secured parliament’s backing.

Protesters during a rally outside the Palace of Justice in Beirut. (AFP/File)

Despite this positive step, Lebanon must still address structural failures in its public institutions, rooted in decades of opacity, fragmented authority and weak accountability.

Zouk of Aviva Investors believes another big challenge to reforming the financial sector will be “the large resistance from banks and their shareholders.

“Without some degree of accountability and transparency, I struggle to see how the rest of the reform agenda can be implemented,” he said.

There are “several proposals being circulated that would run counter to the IMF and would far from restore credibility and trust to the Lebanese financial sector.”

Saidi highlighted the broader challenges Lebanon faces, cautioning that without financing for reconstruction, achieving socioeconomic and political stability will remain elusive.

“If you don’t have financing for reconstruction, you’re not going to have socioeconomic stability, let alone political stability,” he said.

“There has to be a willingness by all parties to go along with the reforms,” he added, highlighting that this is where external support is crucial, particularly from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, France, Europe and the US.

Lebanon endured a 14-month Israel-Hezbollah conflict. (AFP/File)

Saidi said that support must go beyond helping bring the new government to power — it must include assistance, especially in terms of security.

In March, Reuters cited five sources saying the US was engaging with Lebanon’s new government on selecting the central bank governor to combat corruption and prevent the Iran-backed Hezbollah from exploiting the banking system for illicit financing.

A US official who met the candidates before Souaid’s appointment told the news agency that the US was making its guidance on candidates’ qualifications clear to the Lebanese government.

“The guidelines are: No Hezbollah and nobody who has been caught up in corruption. This is essential from an economic perspective,” the official said.

The move, according to Reuters, highlights the US administration’s continued focus on weakening Hezbollah. The group has seen its political and military clout diminished by Israel, which decimated its leadership, drained its finances and depleted its once formidable arsenal.

Firas Modad, a Middle East analyst and founder of Modad Geopolitics, told Arab News that he believes US approval was a prerequisite for selecting the next Banque du Liban governor.

“The next governor is irrelevant,” he said a few days before Souaid’s appointment. “He will need to be approved by the Americans, and the Lebanese system will not appoint someone that the Americans do not approve of.”

Washington is pushing Lebanon’s new government to disarm Hezbollah and address longstanding issues with Israel. (AFP/File)

Modad added that Lebanon faces a stark choice: “Normalization with Israel or civil war.” This decision will “determine whether there is a chance to rebuild the financial system and recover some money for the bondholders and smaller depositors.”

On March 22, the Israeli military mounted airstrikes on Lebanon amid renewed violence in Gaza and Yemen. A “second wave” targeted sites in southern and eastern Lebanon, according to the Israeli military.

Israel claimed that the attacks targeted “Hezbollah command centers, infrastructure sites, terrorists, rocket launchers and a weapons storage facility.” It marked the deadliest escalation since the ceasefire in late November.

Washington is pushing Lebanon’s new government to disarm Hezbollah and address longstanding issues with Israel, including border demarcation and the release of Lebanese captives through enhanced diplomatic talks.

Hezbollah, meanwhile, has rejected calls to disarm as long as Israel continues to occupy Lebanese territory.